It was forty years ago when Jack Hues received a unique education on American drum machines.

Wang Chung, Hues’ band, had signed with Geffen Records and were experiencing a breakthrough hit with a re-recorded version of their song “Dance Hall Days.” This track dominated the US Dance charts, broke into the Top 20, and became ubiquitous on MTV.

Looking towards their next single and video, the band considered “Wait,” a track Hues describes as “very much a drum machine track.” He recalls, “Because the tempo of the track is faster than a real drummer could at that time really play accurately. And so it was deliberately sort of pushed into a realm where only a drum machine could play it.”

In the synth-pop’s Golden Age, Hues believed it was the perfect moment to emphasize the drummer-less nature of the song, despite Wang Chung being a trio with drummer Darren Costin and multi-instrumentalist Nick Feldman.

However, their A&R representative, John Kalodner, swiftly rejected this concept.

“I can recall saying to John, you know, ‘I think that we should make something of that.’ And, basically, it was always kinda like, no. You gotta have a real drummer,” Hues remembers.

Kalodner, a renowned A&R figure known for revitalizing Aerosmith’s career, advised Hues, “If you’re gonna do a video, it’s no good having a drum machine. American audiences won’t get that. They’ll think you’re cheating. They’ll think that you’re whatever. You gotta have the real kit, even if it’s all completely programmed.”

Ultimately, the band chose the funkier “Don’t Be My Enemy” as the follow-up to “Dance Hall Days.” Its music video featured Costin playing a traditional drum kit supplemented with Simmons electronic drum pads. “Wait,” despite being released as the album’s fourth single, never received a video treatment.

“John Kalodner was very much a kind of rock-and-roll guy,” Hues reflects. Even now, he observes with a laugh, “I don’t think record companies have ever got over that. They still want the drummer.”

This summer, Hues is touring America again, participating in two package tours: the Abducted by the ’80s Tour, named after a Wang Chung song and featuring Naked Eyes and The Motels, and the Totally Tubular Festival, alongside Thomas Dolby, Tom Bailey of The Thompson Twins, Modern English, Tommy Tutone, and Annabella Lwin of Bow Wow Wow. (And, yes, Wang Chung’s current lineup includes a drummer.)

The ensuing interview occurred in late 2020, when much of the US and UK were still under lockdown. Hues, whose pop moniker “Jack Hues” is a play on the French phrase “J’accuse,” discussed his history with drum machines. He also spoke passionately about his time at the Royal Academy of Music, his collaborations with Tony Banks of Genesis, and his “lost” album from the early 1990s.

The Dawn of Drum Machines: Early Encounters

One of my initial questions for everyone I’ve interviewed has been about their first encounter with a drum machine, whether on a record, in a home organ setup, or in a music store. This includes even the most rudimentary push-button rhythm boxes. Do you recall your first experience with one?

That’s an intriguing question. Had I anticipated this, I would have given it some thought. But I suppose one of my earliest memories, a sort of fascination, is indeed with those drum boxes that came with organs.

Or I’m also thinking of that square Roland box – I can’t recall the model number, I’m terrible with those. But they would offer rhythms like samba and various preset patterns. One of my favorite albums, still, is Todd Rundgren’s double album, Todd. There’s a track on it, I’m struggling with the title, but I can hear it in my head. It features beautiful, complex chords and opens with a drum machine at a deliberately slow tempo. It’s an instrumental piece. I’ll have to look it up. (Editor’s note: It’s most likely “Sidewalk Cafe,” where Rundgren used a push-button machine, possibly the Roland TR-77 from 1972.)

I particularly adore that track. But in terms of bands, I’ve been in bands since I was about 12. And I tend to agree with Ginger Baker that the drummer is, in a way, about 70 percent of a band’s sound. The feel, their drumming style, their timing – these are crucial.

It’s not just about keeping time; it’s about feeling time. I’ve been lucky to work with some of the world’s best drummers. Drummers like Vinnie Colaiuta or Dony Wynn, they feel time, they work with it. But in your average band, timing can be an issue.

So, the drum machine held this allure of solving that problem, albeit mechanically. I remember Nick and I had a Dr. Rhythm, a simple rectangular box. I’m unsure of its connectivity. (Editor’s note: The Dr. Rhythm was an early programmable drum machine, predating MIDI.)

The BOSS DR-55 Dr. Rhythm, a vintage drum machine used by Wang Chung in their early demos.

We used it in some early Huang Chung demos. We had a small 4-track Fostex setup, and the Dr. Rhythm was often on one track.

I loved it in a way. Drum machines just started and kept going, no fills. You had to work with them, almost trick them into time changes or anything beyond the basic rhythm.

Early Bands and the Democratic Nature of Drum Machines

You mentioned the Dr. Rhythm; did that go back to your early band, 57 Men? (Editor’s note: a band that included Glenn Gregory, later of Heaven 17, and Leigh Gorman, who joined Adam and the Ants and Bow Wow Wow.)

Yes, I think so. When I first met Nick, we worked with Paul Hammond, ex-Atomic Rooster drummer, sadly no longer with us. He was an incredible drummer, amazing timing. He could open a Carlsberg Special Brew and keep a four-on-the-floor rhythm going. (Laughs) He was great. (Editor’s note: This was in the punk-era band The Intellektuals.)

Then we worked with Darren Costin. He was into jazz-rock fusion, Earth, Wind, and Fire, very intricate stuff. Darren was super-cool in that way. Sorry, I’ve drifted from your question.

No problem at all! It’s interesting how this topic allows for tangents. Actually, that leads into another question, but let’s backtrack for a moment.

You were making music throughout the Seventies, witnessing the early evolution of these machines. Some musicians I’ve spoken to have openly said that drum machines and similar tech were very democratic. They opened music to people without traditional skills, providing an avenue they might not have otherwise had.

But you come from a different background, studying at the Royal College of Music. You must have encountered the prevailing attitude towards these machines, especially early on: “They’re toys. Not real instruments. Unsuitable for records.”

Absolutely.

Do you remember that attitude?

It’s interesting you mention the Royal College because I studied electronic music there. But it didn’t involve drum machines. The style we were encouraged to write in was – not even “post-” Stockhausen, as he was still alive – but Stockhausen-esque. Very freeform, using sound as color. A drum machine playing straight through something was unheard of, considered outrageous.

However, early drum machines used electronically created sounds, and those sounds were achievable using a VCS 3 synthesizer, which was my main instrument.

The EMS VCS 3 synthesizer, used in electronic music studies at the Royal College of Music, highlighting the contrast with drum machine technology in the 1970s.

But VCS 3 synths lacked keyboards. Tuning an electronic sound to make a Kraftwerk-style record felt a bit simplistic. Using these sounds, including percussive ones, to create Stockhausen-style soundscapes was more appealing.

The challenge was getting these machines to play in time and in tune. It was incredibly meticulous to get them to play a chord or a coherent rhythm.

Royal College, Punk, and Class in Music

Just to clarify, were you involved in trying to achieve what you just described at the Royal College?

No, not really. At the Royal College, I was torn between fascination with the European avant-garde and an awareness of punk’s appeal. I understood punk’s language well. The avant-garde felt like I’d have to fake it more. I could fake punk more easily.

Class issues in music became apparent at the Royal College. In those days, I was very much a working-class kid, unfamiliar with the middle-class infrastructure of classical music and how crucial it was for success.

Pop music and punk were easier to navigate because I knew people, could write in those genres, and get my work performed.

Huang Chung and the Pursuit of Perfect Timing

I revisited the first Huang Chung record to get a sense of this era. That record, including early singles and B-sides, is all Darren, I assume?

Yes. The Huang Chung album was essentially our live set recorded in the studio. Darren worked hard on that record because we were quite exacting. Getting the tracks to have consistent timing took time. And I’m not just talking metrically.

Huang Chung Album Art

Huang Chung Album Art

The lure of drum machines was strong then, but we didn’t use them. I’m trying to recall if there’s a slow, ballad-like track with a drum machine, but I don’t think so on that record.

If there is, I missed it. But your description of wanting drummers to be precise is what led groups like Steely Dan to have their engineer invent a drum machine before they were readily available.

It was definitely in the air, this idea that you could – I’ve often said that the Eighties, with drum machines and synth technology, especially the Fairlight, promised the perfect pop record. Of course, I know now there’s no such thing.

But there was this sense of controlling all parameters. With drum machines, you could adjust snare, bass drum, hi-hat sounds individually, unlike a kit where everything bleeds together.

You could get everything “perfect,” logically leading to a perfect outcome. Not true, of course. It’s not that simple.

“Dance Hall Days” and the Shuffle Challenge

Along those lines, I listened to the first version of “Dance Hall Days,” produced by Tim Friese-Greene. Before his Talk Talk work on It’s My Life, but he used electronic percussion. Yet, even that first version sounds mostly like a live drummer. Do you recall the setup for that version?

There’s a track called “Ornamental Elephant” that’s a demo with a Dr. Rhythm still present. We lacked time or money to re-record drums in a studio, and I liked the robotic drum machine feel. That track is very synth-heavy, likely no guitars. It hinted at a direction we were exploring. (Editor’s note: “Ornamental Elephant” was the B-side to the 1984 single “Don’t Let Go.” Listen here. Simmons tom overdubs seem to have been added later.)

“Dance Hall Days” is interesting because it’s in 12/8, a shuffle rhythm.

Getting a drum machine to shuffle was incredibly difficult. They don’t “think” in threes mathematically. They think 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, not 3, 9, 12.

You had to “defeat” the machine in programming. I’m unsure if Tim achieved a shuffle feel with a drum machine. But working with Chris Hughes on “Dance Hall Days” was different. He was fascinated with making a LinnDrum shuffle.

How did you manage it in the demo? Did you “defeat the machine” then, or skip it?

I can’t recall the demo sound exactly; I should have researched beforehand! But I think we managed somehow, or maybe we used downbeats based on the snare. Darren played the hi-hat shuffle and toms.

A reason we worked with Chris was his use of that rhythm in Adam and the Ants stuff – the Burundi drums. That influence interested me through my Royal College experience, studying world music, incorporating it into Western pop, already blues-based.

Collaboration with Chris Hughes and Embracing Technology on “Points on the Curve”

Chris mentioned instant chemistry with you guys from the first meeting, leading quickly to working together on Points on the Curve.

Yes.

You mentioned one appealing aspect. By 1981-82, technology had evolved. The first Linn drum machine was out, the second coming. Competitors existed. Machines could do more than a year or two prior. Was the initial thought “This will be a drum machine record”?

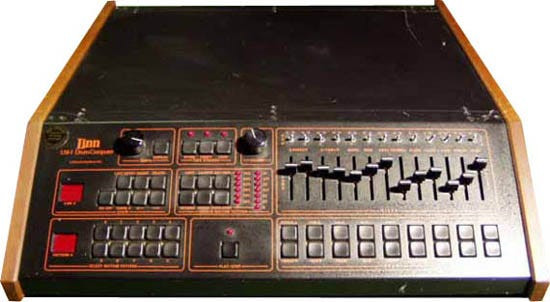

Chris’s fascination with state-of-the-art tech was key. He had an LM-1, a big, expensive machine then. I thought it sounded incredible. His tech interest was part of the promise of this album, embracing technology.

Linn LM-1 Drum MachineThe Linn LM-1 drum machine, a state-of-the-art instrument embraced by Chris Hughes for Wang Chung’s “Points on the Curve” album.

Linn LM-1 Drum MachineThe Linn LM-1 drum machine, a state-of-the-art instrument embraced by Chris Hughes for Wang Chung’s “Points on the Curve” album.

But I was mindful of being signed to Geffen Records in America. John Kalodner was our A&R guy.

John was very rock-and-roll. He later signed Aerosmith, making them huge. They were his dream band. I recall when we had tracks like “Wait” on that album, very much a drum machine track because of the tempo.

I suggested to John we highlight that. But it was always “no.” Gotta have a real drummer.

“If you’re gonna do a video, it’s no good having a drum machine. American audiences won’t get that. They’ll think you’re cheating… You gotta have the real kit, even if it’s all completely programmed.”

The Persistence of the “Real Drummer” Ideal and the ZZ Top Paradox

That’s fascinating to hear, that attitude persisted in America. Maybe UK vs. US difference. The idea that no real drummer, no kit onstage, is cheating.

Yeah. The Eighties plays with this. ZZ Top, rock-and-roll feel and look, but Eliminator is all drum machine.

That’s in my book too!

I imagine it’s pivotal. But you’d never see them with an LM-1 onstage.

They embraced TV, presentation. Concealing technology also happened in the Sixties. This smoke and mirrors aspect puts “real” musicians off pop music. But I found it fascinating.

Electronic Kits and the Drummer’s Role on “Points on the Curve”

Talking about drummers, a compromise was electronic kits like Simmons. Points on the Curve sounds like Simmons, played or triggered. Can you discuss the drummer’s role on that record?

Darren had a Simmons kit and played it live. He liked the electronic aesthetic. He definitely used Simmons sounds and wanted to play whenever possible.

Drummers often spend a lot of time waiting around in studios. On Points on the Curve, much is drum machine, but he triggered sounds or did fills, which we meticulously recreated with machines. Give-and-take between real drummer and machine. But the machine holds the record together.

Darren Costin’s Departure and the Rise of Duos in the 80s

Maybe jumping ahead, after that record and tour, Darren left. Was it related to this – waiting around, parts programmed anyway?

Exactly what you said. Yes.

Even when the drummer normally plays, a machine does his part at that point. Still waiting. Involvement is later, in overdubs.

On the Huang Chung album, he actually played. On Points on the Curve, we played together sometimes in the studio. Everything was recorded meticulously, separately. Darren said, “It’s got my personality because of the fills.” Which is true, the fills are his.

This situation caused drama in bands like ZZ Top and Journey. Was Darren’s departure amicable, or did he feel redundant due to machines?

Essentially amicable. The duo phenomenon in the Eighties is interesting. Record companies saw the core as the writers, financially incentivized through publishing. Bands became somewhat redundant.

Machines taking over drums made it hard for drummers to compete in studios. Listening to tracks hundreds of times reveals live playing anomalies. Eighties aesthetic was shiny, finished. Sloppy drum fills weren’t desirable then, unlike now.

Drummer’s role was questionable. Record companies encouraged writers. Duos like Tears For Fears and us were logical outcomes.

Drum Machines Go Mainstream: From Toys to Standard

People forget how quickly drum machines were adopted. From “toys” in the late Seventies to fully embraced by the mid-Eighties. When did record companies stop insisting on a drum kit in videos to prove real drums?

I don’t think record companies have ever gotten over that. They still want the drummer! (Laughs) Unless you’re Kraftwerk or The Human League, aesthetically, it’s always a guy playing drums.

Fairlight and “To Live and Die in LA” Soundtrack

Chris mentioned Fairlight on Points on the Curve. He used Page R to interface Fairlight and LinnDrum. Was something similar used for the To Live and Die in LA soundtrack?

Working with Page R was excruciating. Sync issues, getting Fairlight to talk to LinnDrum, everything to tape, was a nightmare.

To Live and Die in LA was mainly LinnDrum recorded to tape. Darren had left, so no pretense. Brutally LinnDrum. The main soundtrack piece, “City of the Angels,” a 15-16 minute prog track, derived from “Wait,” faster tempo.

No Fairlight on To Live and Die in LA. LM-1 or LinnDrum for drums. PPG Wave for keyboards, Emulator for strings. Relatively downmarket setup.

We had a week for the soundtrack, Points on the Curve took almost a year. Massive difference in approach. “Elasticity” in “City of the Angels” feel came from LM-1 and Nick playing bass live with the drum machine. Nick’s a great bass player, knows time. His playing with the Linn makes it sound real.

Our engineer got a dirty drum sound, distorting and pushing analog components.

Distorting Drum Machines: Prince and Beyond

I spoke to Prince’s engineer Susan Rogers about him using guitar stomp boxes, distortion, for the LM-1.

I don’t recall stomp boxes, but we drove studio gear hard. LM-1 can sound clinical, just math processing. Driving it was key. We likely used traditional compression and tape distortion. We recorded to analog tape then.

Upgrading Home Setups: Beyond Dr. Rhythm

For songwriting, did you upgrade from the Dr. Rhythm? When did you own machines for personal use?

Interesting. Dr. Rhythm lasted a long time. We were cheap. (Laughs) Fostex 4-track upgraded to 8-track. But Dr. Rhythm stayed. Can’t recall what else we used. Nick might remember.

“Mosaic” and Synclavier Programming with Peter Wolf

Working with Peter Wolf on Mosaic in 1985-86, things changed. You were a duo. Sampling was bigger. What was the setup then?

Peter used a Synclavier and programmed drums on it. Great-sounding machine. Fairlight was excruciating to program and didn’t sound great.

Synclavier was a huge sound upgrade. Still considered one of the best samplers. Drum sounds on “Everybody Have Fun Tonight” are good. But recording in LA, the American aesthetic of “real drummer” prevailed.

Avoiding the machine aspect was key, except for consistency.

Peter’s approach: on “The Flat Horizon,” before the final chorus, insane drum fill. Drummers now can play it. Peter loved creating virtuosic Synclavier effects, not just using it as a drum machine. (Editor’s note: Hear it at 3:28 of “The Flat Horizon.”)

Collaborative Programming and Creative Control

Was Peter primarily programming on Mosaic, or was it collaborative?

Collaborative in that I’d sometimes tut, wanting less flash. But Peter was a control freak about what went on tape.

Keyboard parts, he played them. Drum programs, he programmed them. Required give-and-take. Good results, though some friction.

On the next album, The Warmer Side of Cool, Peter loosened up, let things be more “English.” But he hated the “surf beat,” the skipping snare.

He disliked that slightly amateurish drummer feel, which I paradoxically loved (laughs), despite being obsessed with locked timing. One track I wanted that feel, he refused. “Jeff Porcaro would never play that!” (Laughs)

Not negative about it. Nick and I, English guys, could play, but not like on a Steely Dan record. We aimed for clarity and precision, to a point. Peter was the real deal, played with Zappa.

But players like Darren have personality in their playing. My solos, rhythm parts, flawed, flaws are personality. Important ingredient.

Peter channeled everything onto tape, infused by his approach, good. Record company paid him to do that. They didn’t want my half-assed solo.

“The Anatomy Lesson”: The Unreleased Album

Not drum machine related, but you made an album in the early Nineties, The Anatomy Lesson, unreleased. Why?

Politics. When Wang Chung split, Nick signed to Epic, where our manager David Massey was. I signed to Columbia, where David wasn’t. No one fought for me there. Some at Columbia were pissed David went to Epic.

Not made an example of exactly, but no one cared about my work. No support. Didn’t realize it then.

Naive, thought a great record would be released and supported. Music business isn’t like that.

As far as I know, it’s never surfaced online. What kind of record is it?

Sort of the record I tried to make in Wang Chung, slightly prog. Polished, complex textures. Brass, keyboards, strings. Steve Ferrone on drums, great drums. Good in many ways, but ambitious. (Laughs) “Good” is meaningless. But ambitious. Some parts work, some don’t. Maybe I’ll release it someday.

Painful experience, putting effort into something unseen. My first bad record business experience. Previously indulged as artists should be. Hit a wall, my fault. Tough but a learning curve, made me better.

Who produced it?

Nick Davis, who worked with Genesis then. It followed from – no, I met Nick first. Then worked with Tony Banks. (Editor’s note: on the 1995 album Strictly Inc.)

So that connection led to that collaboration.

Exactly.

I assume Sony still owns The Anatomy Lesson.

Yeah. Columbia. Status unclear.

Manager at the time, nameless, if more on the ball, could have gotten me out of the deal. Clauses for payoff, but I – English way, never looked at small print. David cushioned me from that side of the business. Status with Columbia owning it is unclear.

Drum Machines Post-Standalone Era and “Tazer Up!”

By the early Nineties, standalone drum machines were largely replaced by samplers, workstations, computer recording.

When did you leave standalone machines behind? During that unreleased record?

No. On that record, Steve Ferrone played drums. Learned in LA, want the “real thing,” not drum machines, unless for a specific sound.

Drum machines underpinned demos, but not used on the record. Trying to recall what I used then. Emulator maybe… long time, blanked it out.

But hearing Portishead, Fat Boy Slim, early Massive Attack, using sampled loops, clearly not real playing, looped. I found that fascinating. Breath of fresh air from strict drum machines, programming, defeating metronomic tendencies.

I recall reading after you and Nick reunited, you’d go back to machines, programmed parts.

Yes, Tazer Up!, made in 2011-2012. Worked on it on and off for 3-4 years with Adam Wren. Engineer on Leftfield albums, still works with them.

Adam’s a great engineer. Very English – into broken, dirty, messed up sounds, but meticulous.

Nick and I reunited for business reasons, touring offers, we took them. I thought we should have an album, something to sell, radio/TV interviews, something to talk about.

Media cares less about tours. An album provides focus. Plus, I write songs. Writing rate increased recently.

Even then, a couple of songs a year I liked. Songs lying around. We discussed: what’s 21st-century Wang Chung? Our records were drum box, synth, guitars, vocals.

Drum box and guitars combo we liked, not just synth band. Tazer Up! rooted in that aesthetic, no loops mostly. Approach was drum box.

“Stargazing” on that album, a 6-7 minute prog epic. Demo used a DJ Shadow loop, sloppy. Replaced with programmed TR-808 samples for drums. Curious feel. I still prefer the DJ Shadow loop. But the drum machine playing stadium-rock piece is more stylish, self-contradictory.

Hardware vs. Software Drum Machines: Tactility and Sound

Hardware vs. software drum machines is divisive.

Some say hardware’s tactile feel is unbeatable. LM-1 has its own “time,” computer time doesn’t match.

Others say software plug-ins offer any sound, got rid of “hardware junk.” Tazer Up!, where do you stand on hardware vs. software?

Interesting. I used an MPC 60 for years, roughly 2000 onwards. Tazer Up! initially used MPC 60.

The Akai MPC 60, a hardware sampler and drum machine used by Jack Hues in the 2000s and during the initial phases of Wang Chung’s “Tazer Up!” album.

Not doctrinaire about machines. I found them a pain. Prefer current software.

But certain – working with Tony Banks, album close to later Gabriel Genesis, Selling England by the Pound, Foxtrot, albums I loved.

Road crew said Mellotron and old gear was in storage, could set it up. I asked Tony, why not? He paled, “Don’t. No.”

“I’m happy with this machine.” Yamaha keyboard for everything. I said, “Not the same reaction playing it.”

He said, “I don’t wanna react like that, don’t wanna be reminded of nightmare dealing with that stuff.” Romance around technology, but reality, especially for the one dealing with it, is that all-in-one software is preferable. Younger people seem more romantic about hardware.

Recording to tape, friends love the idea, “studio in Ramsgate, record to tape.” Doesn’t magically sound great. Sounds awful unless you know machine setup, compress everything.

So Tazer Up! is more a computer record using vintage drum machine sounds.

Yes. No real drummers. Programmed, Adam using loops, bits of loops, sounds he had. Leftfield sense of making drum box sound huge.

Fun to work with, liked that process. But recent stuff, solo album Primitif released this year –

Which I love, by the way. Been listening past weeks. Unfortunately, like everything now, “Didn’t know it came out!” But now I do.

Getting people aware is as hard as ever.

Well, I really enjoyed it a lot.

I appreciate that. Proud of it.

What I enjoyed with that record was live playing. Best of both worlds. Not just pressing a button, locked in place. You do that, but then loosen things up, get rid of divisions, looser feel.

Finishing another album, working on it during lockdown, great way to spend time. Josh McGill [of Syd Arthur] played again. Enjoyed leaving tracks of just his playing. Some tracks now, no click track. Just play, work around that.

Tracks on Primitif like that, “A Long Time.” No click track, indeterminate pauses. Career largely click tracks in background, even with real drummers. Releasing from click track and tempo strictures is something I’ve shaken off, tracks in different tempos by the end.

Remember Leonard Bernstein, classical music fan, disciplines around it. Synclavier given to him early on. Great composer, conductor. He liked it, but couldn’t understand it couldn’t handle rubato in classical music. Slowing down, speeding up, expressive playing. Synclavier calculated rubato as metronomic time, very tight divisions. He thought Synclavier was a toy. Perspective matters.

Best Drum Programmer and the Human Element

Subjective question – genre-dependent. Best drum programmer you’ve seen, heard, worked with?

DJ Shadow, actually. Drum programming on …Endtroducing and The Private Press is stunning. Love his work.

Him. Many others great. Geoff Barrow on Portishead records. Adam’s great, good programmer.

Worked with jazz musicians, jazz drummers, drum machines are the devil to them.

Funny, working with Josh on this new album, track with solo trumpet, Miles-inspired.

Drums come in last third of track. Deliberately played so “one” is unclear, wanted illusion. Illusion? No, not really. Never figured out where “one” was.

Like musicians watching each other, waiting for boof. Josh played along, inventing part. Did slightly out-of-time, falling-over stuff, I used it. Recording, I said, “Don’t do that. No jazz drama. Hold time, pull together.”

He did 10 takes of that, never used them. Used the falling-over stuff, sounded right. We talked about Mark Holub, drummer I’ve worked with on jazz stuff, Led Bib band. Won Mercury Prize, post-Ornette Coleman free jazz.

Mark’s playing is filigreed, insane detail. Never just holds a beat. Will do it beautifully if asked.

But natural state is hazy detail obsession. Maybe talk to him about drum machines, polar opposite of me and Nick with Dr. Rhythm. (laughs) Interesting competing viewpoint.

Drum machines are fascinating. Chris talking about it, great topic to write about. Feel of drums, record – Ringo, Steve Gadd, or whoever programmed Human League’s Dare album. That feel is huge in music. Maybe the first bit that touches you. How drum machines are part of that feel – very interesting.

Tune in for more exclusive interviews about drum machines and electronic percussion, coming soon! (Really this time 🙂 Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com. And be sure to visit the official Wang Chung website, where you can get tickets for the band’s summer tour of the U.S.!

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers.

Thanks for reading Dan LeRoy’s Bonus Beats! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.