Pagan gatherings often present a stark contrast to mainstream societal norms, particularly in their approach to nudity. Recently, attending such a gathering held in the secluded woods of farm country, I witnessed firsthand the diverse expressions of nudity within pagan rituals. From revealing attire to complete nakedness, both men and women participated in varying degrees of undress. This experience, far removed from the often-scandalized perception of nudity in Puritanical cultures, prompted a deeper reflection on the meaning and impact of Women Dancing Nude within these spiritual contexts.

My personal encounters with public nudity have been limited, confined to a few pagan festivals and never venturing into nude beaches. Following this recent gathering, I revisited an article I penned in 2011 after my initial exposure to pagan nudity. Rereading it now, I find myself questioning its perspective, particularly concerning the portrayal of women. Does it inadvertently objectify women, reducing them to mere figures for the male gaze, devoid of personal narratives and agency? This is a critical question, and I am eager to hear diverse perspectives, especially from female readers, to understand if my reflections truly capture the relationality and respect that should be inherent in discussions about women dancing nude.

My journey into understanding pagan nudity began at the Pagan Spirit Gathering (PSG) in 2011. As a newcomer to such events and having no prior experience with ritual nudity, I approached the subject with a degree of apprehension. At PSG, I encountered both men and women embracing nudity in various forms. Surprisingly, this initial encounter proved to be a profoundly healing experience, challenging preconceived notions and fostering a new sense of comfort with the human form.

As a man discussing female nudity, I recognize the sensitive ground I tread. Western culture often casts men as the active viewers and women as passive objects of observation, a dynamic that has historically contributed to the subjugation of women. Therefore, any account from a male perspective on witnessing female nudity in pagan settings requires careful consideration, especially within the context of the generally liberated values of Paganism.

Phryne before the Areopagus: A classical depiction of public nudity, raising questions of voyeurism and judgment.

My personal history with female nudity has been complex, shaped significantly by a Christian upbringing. Reflecting on this, I recall the book Men Confront Pornography, edited by Michael Kimmel. One essay explored the pivotal role of male visual experience, specifically in looking at women, within the male psyche. It discussed the often-unconscious conflict men face: society encourages them to look at women, they experience arousal, yet they are simultaneously shamed for both the act of looking and the resulting arousal. This inherent ambiguity in the male gaze, I believe, lies at the core of misogyny.

During my Christian years, this internal battle between arousal and guilt was a defining struggle. Leaving Christianity marked a step towards healing, allowing me to view women without immediate judgment. This included casual encounters in public and even engaging with pornography and erotic art, practices previously laden with shame.

Furthering this shift was David Deida’s book, The Way of the Superior Man. Deida proposes that arousal is not a choice but a natural energetic exchange between masculine and feminine energies, regardless of sexual orientation. He suggests embracing the desire a woman evokes as a “blessing, one of nature’s gifts.” Though I encountered this idea before embracing Paganism, it now deeply resonates with my Pagan sensibilities.

Deida offers a practice to transform the visual experience of women:

“The next time you come upon a woman who sends a thrill through your body, relax into the thrill. Let her waves of feminine energy move through your body like a deep massage. Breathe fully, without resisting the joy her sighting affords you. Breathe the joy all through your body, down to your toes. Don’t stare at her … when you see her, and experience your attraction, fully allow the energy of the attraction to move freely through your body. … As you behold her, receive her vision as a blessing.”

Deida applies tantric breathing to the act of looking. Men often unconsciously hold their breath as they approach orgasm. Conscious, regular breathing during intercourse can prolong pleasure. Similarly, we often restrict breath when looking at women, a subtle physical manifestation of an unconscious need for control.

The Woman, the Man, and the Serpent: Note the rigid posture and clenched fists of Adam, suggesting a struggle with control and natural flow.

Natural breathing when observing an arousing person signifies letting go. Inhaling becomes receiving beauty, and exhaling, releasing it back. This is akin to appreciating a flower’s beauty without picking it, preserving its life. The urge to possess these moments of beauty, to grasp them, diminishes their essence, transforming art into mere pornography by fixating on possession rather than appreciation. This aligns with Alan Watts’ concept of “the possessive will,” attempting to freeze fleeting beauty into permanent ownership, thereby killing its living essence.

This simple breathing exercise revolutionized my visual experience of women, shifting it from a possessive gaze to one of appreciation, reducing objectification because objects are inherently possessable.

Returning to PSG 2011, I encountered three distinct forms of nudity, focusing here on female nudity due to my personal history as a heterosexual male (male nudity being a topic for another time). The first was the completely un-self-conscious, non-erotic nudity observed during workshops and gatherings.

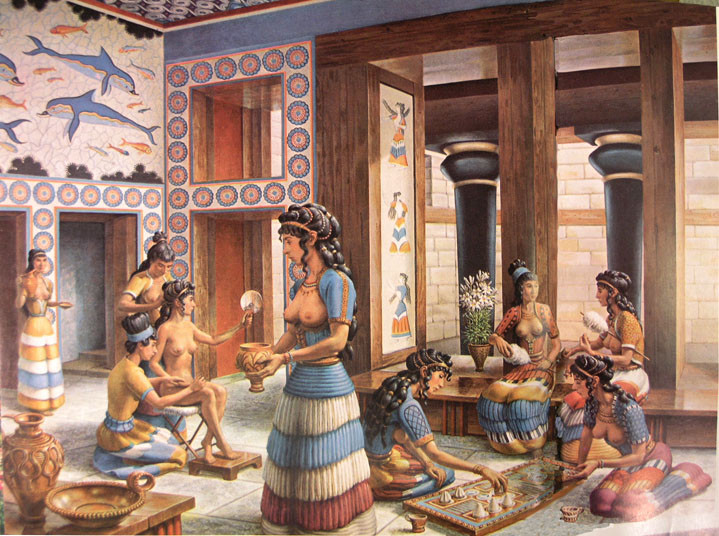

Minoan Palace Scene: Depictions of ancient cultures often reveal a more relaxed and integrated view of nudity in daily life and ritual.

This was profoundly healing. The women, partially or fully nude, exuded comfort, mirrored by those around them. It allowed me to release the Puritanical fixation on nude bodies ingrained by mainstream culture, at least temporarily.

Leopard-enthroned goddess from Çatal Hüyük: Ancient goddess figures often emphasize the power and divinity of the female form, irrespective of conventional beauty standards.

I began to appreciate the beauty of bodies I might not typically find attractive. At the festival, all bodies possessed a unique beauty, a divine quality. Sitting across from a woman in a workshop, breasts bared, transcended mainstream beauty standards, embodying a divine feminine physicality. This evoked a scene from HBO’s Rome, where an obese woman, painted red, received offerings as a living idol of Bona Dea. I termed this “Bona Dea nudity.”

The second type emerged at Pan’s Ball, which was disappointing. Hoped to be a sacred Bacchanalia, it felt more like a self-conscious frat party. The nudity, both male and female, lacked sacramental quality, feeling forced and self-aware, making me equally uncomfortable.

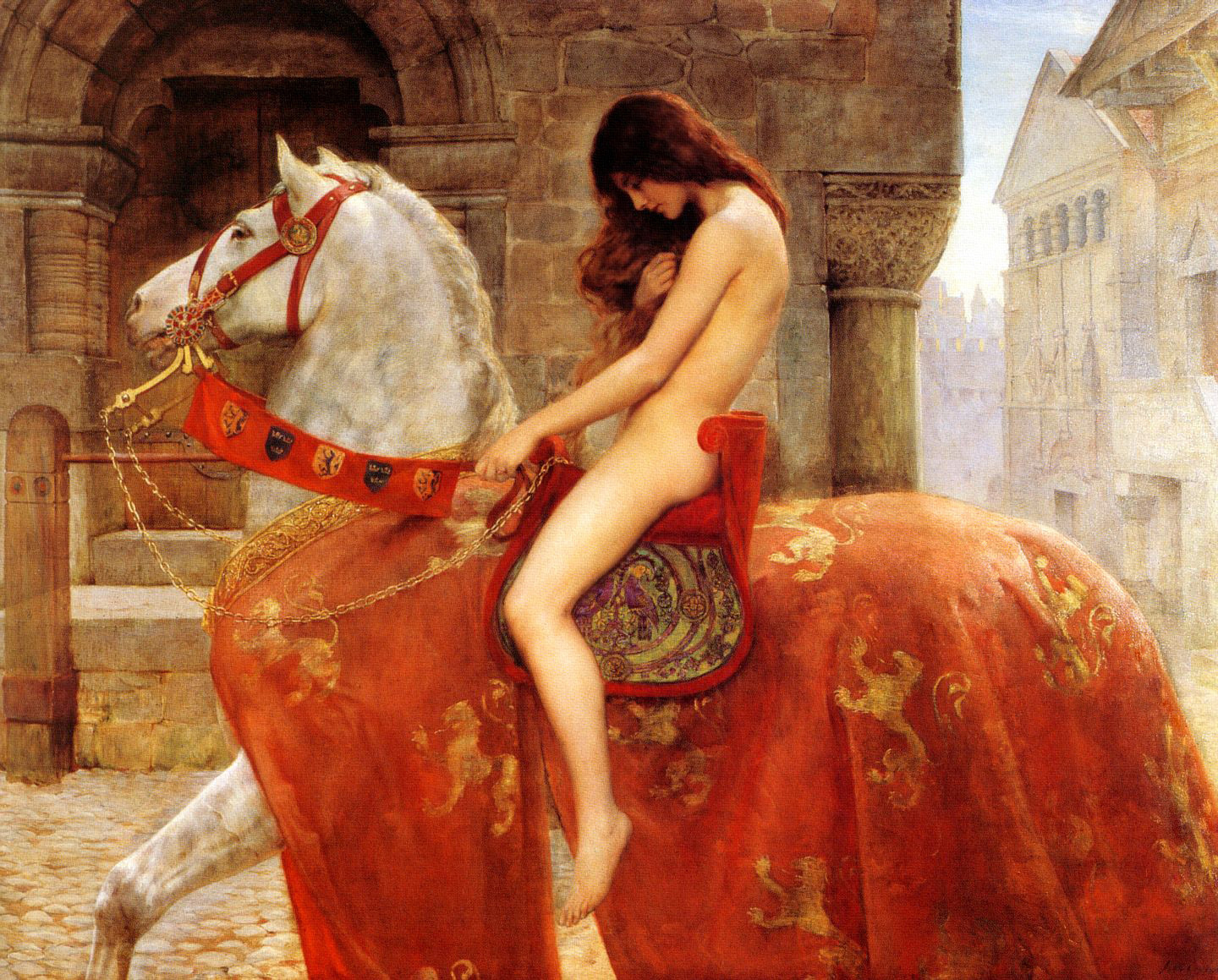

Lady Godiva: A historical example of nudity as protest, yet often romanticized and potentially sexualized in its depiction.

It mirrored the difference between French and American cinema. French films, though potentially showing more nudity, are less self-conscious about sex than American films, which often seem to revel in their own “naughtiness.” This self-consciousness arises from the societal obsession with stigmatized subjects. While aroused at Pan’s Ball, I was uneasy and left early. I labeled this “pseudo-bacchante nudity.”

The third type occurred during a late-night drumming circle. Women danced around a fire. One young woman, with striking breasts, presented one of the most erotic experiences of my life, yet I felt surprisingly comfortable.

This “true bacchante nudity” combined the un-self-consciousness of “Bona Dea nudity” with the arousal of “pseudo-bacchante nudity.” It was the most healing, sacralizing both the women’s bodies and my own arousal.

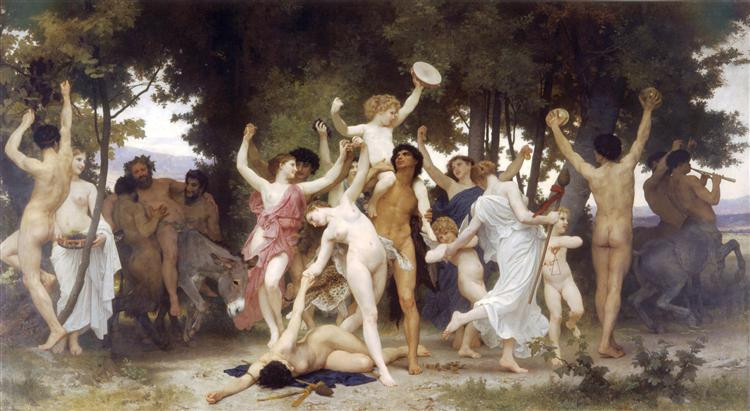

The Youth of Bacchus: Representing the ecstatic and sacred dimensions of dance and nudity in ancient Bacchic rituals.

It was erotic yet sacred, validating Anne Rice’s assertion that “the erotic and the wholesome are not mutually exclusive,” a core Neopagan ethic. Could this be what St. Ambrose meant by “casta meretrix,” the “chaste prostitute”? Is this longing for sacred eroticism the root of the Madonna-whore complex? Could such experiences heal men’s unhealthy views of women?

Looking back after years, this article troubles me. Does it still objectify women despite my intentions? What are your thoughts? Female perspectives are particularly welcome.

P.S. For another perspective, Tom Swiss’s article, “The Zen Pagan: Wild Naked Pagans,” offers valuable insights into his experience with pagan nudity: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/agora/2014/09/the-zen-pagan-wild-naked-pagans/.

Share this:

Like Loading…