In 1949, a simple step changed the landscape of American dance. Alvin Ailey, then a young gymnast, followed his school friend Carmen de Lavallade to the Lester Horton Dance Theater in Los Angeles. This pivotal moment ignited a legacy that continues to resonate, embodying the powerful message: we can dance, we can dance, we can dance. From Horton’s mentorship to the establishment of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in New York, Ailey forged an intersectional lineage that wove together dance, art, and countless human stories. This rich history is now celebrated in a groundbreaking exhibition, five years in the making, at The Whitney Museum of American Art: Edges of Ailey.

Alvin Ailey

Alvin Ailey

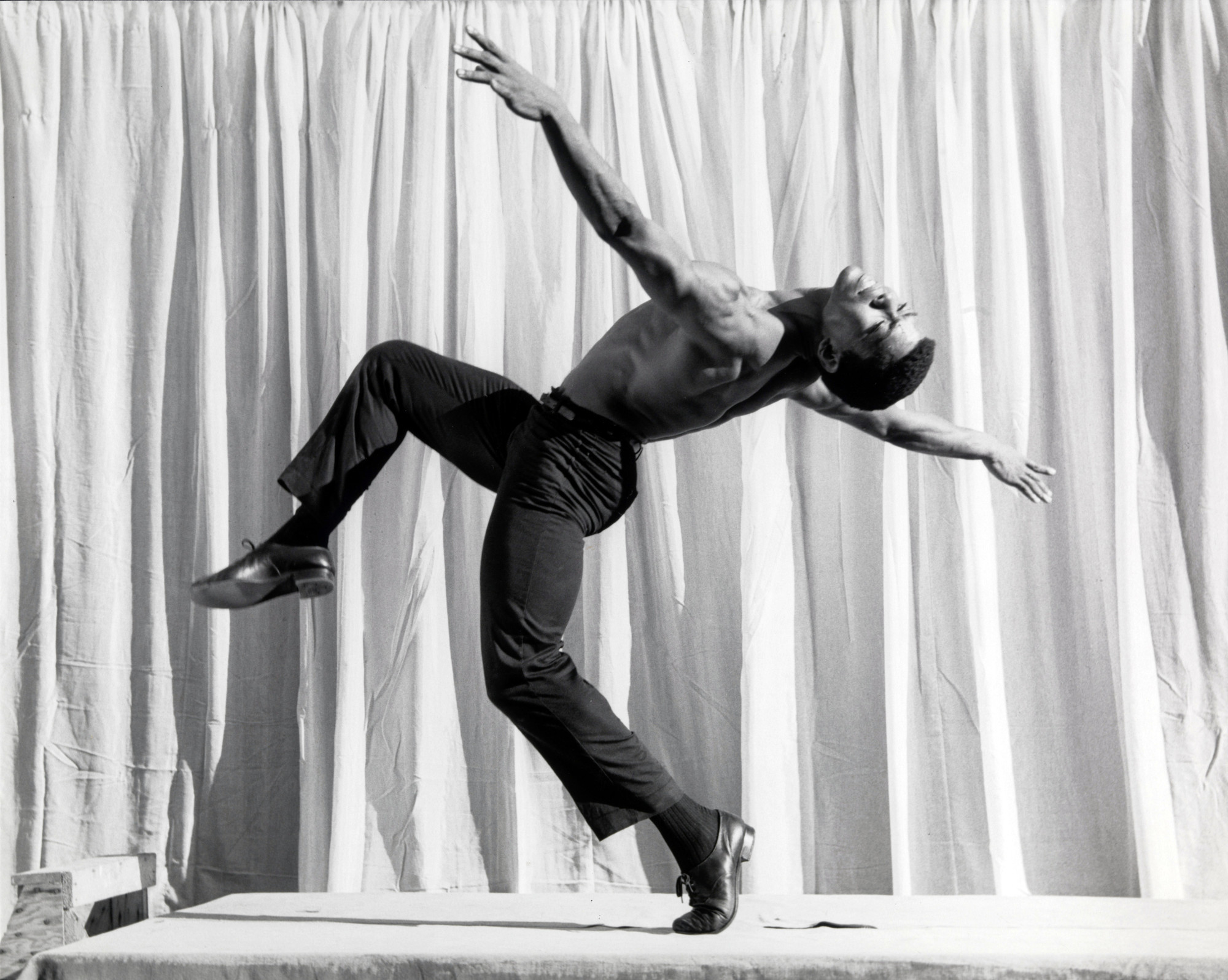

Alvin Ailey in a striking black and white portrait, captured by John Lindquist around 1960, showcasing the early days of a dance icon.

Brontez Purnell, reflecting on his own dance background, recounts his emotional experience at the exhibition, recognizing the profound impact of the Ailey tradition. “Ailey is not just Afro-American dance language; it is the American dance language,” he asserts. This sentiment captures the essence of Ailey’s vision: dance as a universal language, accessible to all, a powerful declaration that we can dance, we can dance, we can dance. The exhibition, curated by Adrienne Edwards, carries a poignant undertone, acknowledging the recent passing of Judith Jamison, Ailey’s muse and long-time artistic director. Yet, it remains a vibrant celebration of life and art. In a conversation with three of Ailey’s esteemed protégés—Masazumi Chaya, Donna Wood Sanders, and Sylvia Waters—Purnell delves into the enduring legacies of Ailey and Jamison.

Sylvia Waters begins by acknowledging the heavy atmosphere surrounding the exhibition’s opening, so soon after Jamison’s death. The immediate priority, she explains, was to honor Jamison’s monumental contribution. Despite the profound loss, the focus shifted to celebrating her legacy and sharing it with the world. This commitment to celebrating life, even in mourning, mirrors the spirit of Ailey’s work, reminding us that even in sorrow, we can dance, we can dance, we can dance – as an act of remembrance, resilience, and joy.

Donna Wood Sanders emphasizes the global impact of Judith Jamison, highlighting the universal reach of her influence. The memorial service, Sanders recalls, showcased the multi-generational impact of Jamison, from her contemporaries to the youngest students of the Ailey School. This intergenerational connection underscores the enduring power of the Ailey legacy, ensuring that the message of “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” resonates across time.

Masazumi Chaya shares a personal anecdote, affectionately referring to Jamison as his “mother” due to their roles in a dance piece. He describes the memorial as difficult yet peaceful, sensing Jamison’s readiness and the vast legacy of love she left behind. This love, Chaya suggests, fuels the continued work of the company and inspires artists across disciplines, reinforcing the idea that through art and dance, we can dance, we can dance, we can dance towards a brighter future.

Alvin Ailey

Alvin Ailey

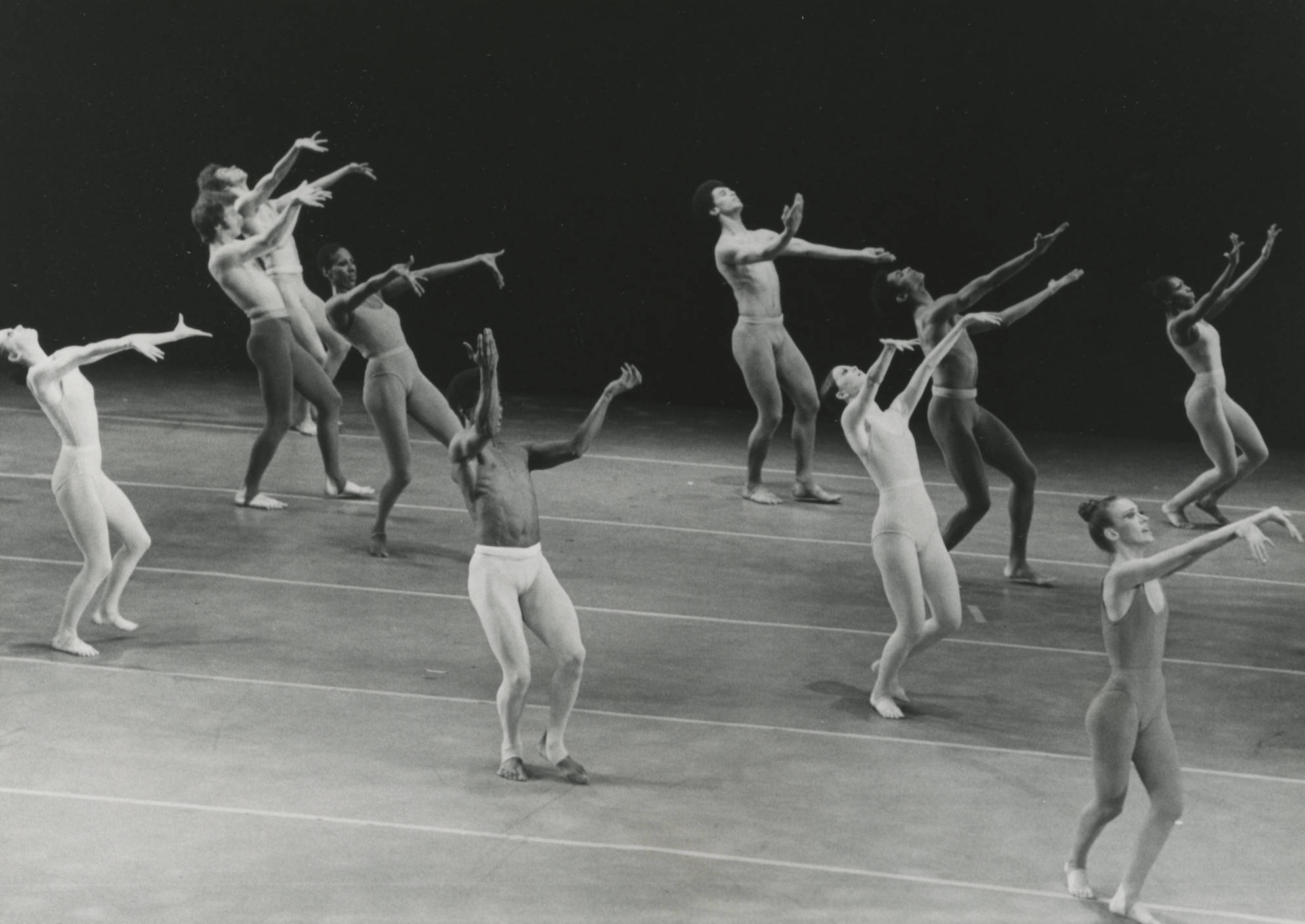

A captivating vintage photograph from around 1970 featuring Judith Jamison alongside Clive Thompson and fellow dancers in “Streams,” capturing a moment of grace and artistry.

Waters recalls Alvin Ailey’s phrase, “moved on up to a higher calling,” reflecting on Jamison’s dedication to Ailey’s vision. Jamison, she explains, considered it her “calling” to nurture and expand Ailey’s “garden” of art. Her refined taste and unwavering commitment to beauty were integral to this mission. This dedication to artistic excellence is a cornerstone of the Ailey legacy, pushing boundaries and inspiring generations to believe that we can dance, we can dance, we can dance at the highest levels of artistry.

Purnell then steers the conversation towards the personal beginnings of these dancers with Ailey and Jamison. Waters recounts two memorable encounters with Alvin Ailey. The first, a chance sighting on the streets of New York, left a lasting impression. Weeks later, she found herself in Ailey’s dance class, a serendipitous beginning to a lifelong journey in dance. Her first meeting with Judith Jamison in Paris was equally impactful, a brief but memorable introduction to a future friend and colleague. Years later, a chance street encounter solidified their bond, transforming “Judith” into “Judy,” a warm and welcoming friend. These personal stories reveal the human connection at the heart of the Ailey company, a community built on shared passion and the belief that we can dance, we can dance, we can dance together.

Donna Wood Sanders joined the company at just 17, initially intimidated but quickly embraced by the Ailey family. She recalls the intensive training and the immersive experience of touring, forging deep bonds with her fellow dancers and mentors. This sense of family and shared experience is crucial to the Ailey ethos, fostering an environment where everyone feels empowered to say “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” regardless of background or age.

Masazumi Chaya’s audition story involves Judith Jamison nonchalantly doing a crossword puzzle while observing dancers. Despite her seemingly detached demeanor, Jamison and Ailey recognized Chaya’s talent, inviting him to join the company. This unexpected encounter led to a cherished mentorship, symbolized by a ring Jamison gifted to Chaya, which he still wears. He fondly remembers evenings spent at Jamison’s apartment, highlighting her love for cooking and creating a home away from home for the dancers. These personal touches reveal the nurturing environment cultivated by Ailey and Jamison, reinforcing the message that within the Ailey community, “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” with support and encouragement.

Purnell shifts the focus to the Edges of Ailey exhibition itself, noting its broader scope compared to exhibitions focused on individual figures like Martha Graham. The Ailey exhibition encompasses a wider range of influences, including Lester Horton, Katherine Dunham, and various filmmakers. Waters explains that Adrienne Edwards, the curator, envisioned a comprehensive exploration of Ailey’s world. The Ailey archives, under archivist Dominic Singer, provided a wealth of materials—photographs, film footage, journals—to shape the exhibition. Waters admits she was initially unaware of the exhibition’s ambitious scale, impressed by Edwards’ deep dive into Ailey’s persona and the immersive, multi-artist presentation. This expansive approach mirrors Ailey’s own inclusive vision of dance, demonstrating that “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” encompasses diverse styles, histories, and artistic expressions.

Chaya adds that the exhibition was a five-year undertaking, initiated by Edwards’ vision to honor Alvin Ailey. This lengthy process underscores the depth and complexity of Ailey’s legacy, requiring extensive research and collaboration to fully capture its essence. The dedication to such a thorough exploration reflects the profound impact of Ailey’s work and the importance of preserving and celebrating his contributions to dance and culture, reminding us that his influence ensures “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” for generations to come.

An installation view of “Edges of Ailey” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, showcasing Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s artwork “A Knave Made Manifest” from 2024, within the context of the Ailey exhibition.

Sanders emphasizes the hands-on involvement of Waters and Chaya in the exhibition’s development, noting their invaluable contributions in providing archival materials. Sanders herself contributed original tour and casting sheets from her time with the company, highlighting the collaborative effort to bring the exhibition to life. This collaborative spirit mirrors the communal nature of dance itself, emphasizing that “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” is often a collective endeavor, built on shared memories and resources.

Waters acknowledges Sanders’ remarkable archive of photos and documents, especially from a pre-digital era. Sanders’ dedication to preserving these memories provided crucial insights into the company’s history, enriching the exhibition and ensuring a comprehensive portrayal of the Ailey legacy. These personal archives serve as tangible reminders of the company’s journey and the many individuals who contributed to the powerful message that “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” across the globe.

Purnell inquires about the curation of the 80 performances accompanying the exhibition. Waters explains that Adrienne Edwards collaborated with Robert Battle, then the company’s artistic director, to select choreographers who were part of Ailey’s artistic circle. The performances also showcased the diverse components of the Ailey organization—the main company, Ailey II, and students from the school and extension programs. This multifaceted approach to the performances mirrors Ailey’s own commitment to fostering talent at all levels, ensuring that the opportunity to “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” is extended to aspiring dancers of all ages and backgrounds.

Waters recounts Ailey’s openness to emerging choreographers, mentioning Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane as examples. Ailey’s philosophy, “dance came from the people. It should be given back to the people,” underscores his belief in accessibility and inclusivity. This core principle is reflected in the exhibition and the accompanying performances, all reinforcing the central message that “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” is an invitation to everyone.

Waters poignantly notes Judith Jamison’s absence from the exhibition opening, expressing her own emotional experience of delivering Jamison’s intended opening night speech. Despite the sadness, Waters emphasizes the harmonious collaboration between the curators, Whitney staff, and Ailey organization in bringing the exhibition to fruition. She praises the immersive nature of the exhibition and its comprehensive catalog. This collective achievement, realized even in the face of loss, embodies the resilience and enduring spirit of the Ailey community, proving that even in grief, “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” to honor and celebrate those who have inspired us.

A vintage poster announcing an Alvin Ailey YWCA Clark Center performance, captured by Jack Mitchell, a visual reminder of the early performances that laid the foundation for a dance empire.

Sanders reflects on the historical significance of their collective journey with the Ailey company, emphasizing that they were “busy just doing,” creating a legacy without fully realizing its future impact. She recalls working with legendary figures like Talley Beatty and tributes to Duke Ellington, Maya Angelou, and Sidney Poitier, highlighting the incredible creative forces that converged within the Ailey world. This retrospective view underscores the profound and lasting impact of their work, demonstrating that their dedication to dance has ensured that “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” will continue to inspire future generations.

Sanders marvels at the evolution of the Ailey organization, from a small company of 18 dancers rehearsing in a church to a 32-dancer company housed in the “Glass Palace of Dance,” the Joan Weill Center for Dance. This phenomenal growth, she explains, is a testament to the enduring power of Ailey’s vision and the unwavering support of individuals like Judith Jamison, who spearheaded the creation of their current home. This physical and artistic growth symbolizes the expanding reach of Ailey’s message, proving that “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” can flourish and evolve beyond initial dreams.

Waters recounts the company’s journey from its beginnings at 59th Street to the Joan Weill Center for Dance, emphasizing Judith Jamison’s pivotal role in securing the “Glass Palace.” She shares Ailey’s belief that a dance company needs both financial stability and a dedicated home to thrive. Waters then shares a cherished quote from Ailey: “What I’m trying to do is to hold up a mirror to society so that people can see how beautiful they are.” This powerful quote encapsulates Ailey’s artistic mission: to use dance as a tool for reflection, empowerment, and celebrating the inherent beauty within everyone, reinforcing the inclusive message of “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance“.

Purnell expresses his emotional response to the conversation and the Ailey legacy. Chaya emphasizes Jamison’s dedication to teaching, even after stepping down as artistic director. Her commitment to nurturing young dancers ensures the continuation of the Ailey tradition, passing down the belief that “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance” to future generations.

Waters wholeheartedly agrees, extending an invitation to Purnell to take a class at the Ailey School, playfully adding, “If you can walk, you can dance.” This welcoming invitation embodies the Ailey spirit of inclusivity and accessibility, reinforcing the message that dance is for everyone, and indeed, “we can dance, we can dance, we can dance.”

Purnell reveals his dance background, mentioning his dance degree and upcoming performance of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring in New York, extending an invitation to Waters and Chaya to attend. The conversation concludes with mutual gratitude and holiday wishes, leaving a lasting impression of the Ailey legacy’s warmth, inspiration, and enduring message: we can dance, we can dance, we can dance.

A program cover from Alvin Ailey’s performance at Stockholm Stadsteatern in 1965, a historical artifact that highlights the international reach of his dance company early in its history.