There’s a persistent misconception that queer culture remained hidden until the social movements of the 1960s. This myth suggests that LGBTQ+ individuals lived in isolation and obscurity, their lives largely invisible to the public eye. However, historical evidence reveals a vibrant and public queer existence long before the 1960s. From the late 1800s onwards, spaces like saloons, cabarets, speakeasies, rent parties, and drag balls served as crucial havens where LGBTQ+ identities were not only visible but actively celebrated. New York City, particularly Harlem, emerged as a significant hub for these communities.

Richardbrucenugent.jpg

Richardbrucenugent.jpg

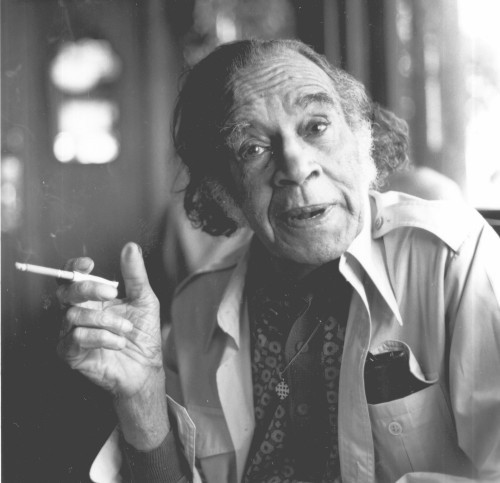

Richard Bruce Nugent, prominent figure of the Harlem Renaissance, Wikimedia Commons.

The early 20th century witnessed the flourishing of a distinct Black LGBTQ+ culture in Harlem, significantly shaped by the Harlem Renaissance (1920-1935). This intellectual, cultural, and artistic movement profoundly impacted the neighborhood, fostering a surge of literature, art, and music centered around Black experiences. Notably, many leaders of this movement identified as gay or bisexual, or expressed nuanced sexualities. Figures such as Angelina Weld Grimké, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Wallace Thurman, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Alain Locke, and Richard Bruce Nugent, among others, challenged societal norms and explored the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality through their work. The Harlem Renaissance provided a vital vocabulary for understanding these complex and evolving identities.

Harlem’s legacy as a vibrant center for LGBTQ+ art, activism, and culture continued to grow. Therefore, it is no surprise that Harlem is recognized as the birthplace of Voguing Dance, a highly stylized and expressive dance form developed within Black and Latino LGBTQ+ communities. During the 1960s to 1980s, New York drag ball competitions, initially focused on elaborate pageantry, transformed into dynamic “vogue” battles. These balls became the heart of ballroom culture, where Black and Latino voguers competed for trophies and prestige, representing their “Houses” – groups that functioned as both competitive teams and chosen families. Taking its name from the famous fashion magazine Vogue, voguing drew inspiration from high fashion poses and ancient Egyptian art, incorporating exaggerated hand gestures to narrate stories and embody diverse gender expressions within established drag categories.

Through voguing dance, drag queens masterfully demonstrated gender as a performance. They mimed applying makeup (“beat face”), styling hair, and donning extravagant attire, highlighting the constructed nature of gender presentation. This inventive performance aspect of voguing even served as a non-violent method for resolving disputes among rivals, fostering an environment of mutual respect and understanding within the ballroom scene. Voguers engaged in “reading” each other through dance and pantomime, with the ultimate victor being the one who delivered the most cutting and stylish “shade.”

Over time, voguing evolved from the “Old Way,” characterized by sharp angles and linear movements, to the “New Way” in the late 1980s. “New Way” voguing incorporated elements like the catwalk, the duckwalk, spins, “bussey” (body rolls), and emphasized hand performance. Contemporary “New Way” is distinguished by more rigid movements and “clicks,” or joint contortions. “Vogue Fem” emerged as another prominent style, retaining “New Way” elements but prioritizing speed, fluidity, and acrobatic stunts. Regardless of the specific style, voguing stands as a testament to the courage and creativity of Black and Latino LGBTQ+ communities, transforming personal expression into a powerful art form. Voguing dance provides a profound sense of identity, belonging, and dignity in a world that often marginalizes their lives.

Jennie Livingston’s groundbreaking documentary, Paris is Burning, offers a crucial glimpse into the history of voguing during the mid-to-late 1980s. This iconic film captured the lives of prominent voguers within New York’s ballroom scene, illuminating the challenges they faced due to racism, homophobia, classism, and the AIDS crisis. While celebrated as an invaluable historical document of LGBTQ+ communities of color, Paris is Burning has also faced significant criticism. Many voguers featured in the film were from working-class backgrounds, living in poverty, and engaged in sex work. Some even struggled with homelessness and HIV/AIDS. Despite their central role in the film’s creation, they were inadequately compensated for their participation, leading to legal action.

Feminist scholars like bell hooks raised critical questions about Livingston’s position as a white filmmaker. Hooks argued that the film, without sufficient critical framing, could be interpreted as voguers simply mimicking the very structures that oppress them, rather than subverting them. Conversely, other scholars contend that the act of imitation within voguing creates a vital Black imaginative space where aesthetics and LGBTQ+ life can be explored in all their intricate complexity and nuance.

These complex issues surrounding race, representation, and appropriation in relation to voguing dance remain relevant today. Addressing these concerns is essential to preserve and honor traditions that are inherently Black, Brown, and LGBTQ+, and to definitively dispel the damaging myth that LGBTQ+ lives of color were never openly and publicly lived.

Explore the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Cultural Expressions exhibition to delve deeper into social dance and gestures!