Stepping into Roseland Ballroom, affectionately known as Roseland Dance City, in 1978 was like entering a time capsule. Drawn in by a tribute to Cuban music icon Miguelito Valdés, an event seemingly lost to collective memory, I was immediately struck by the sheer scale of the venue, particularly its expansive dance floor. At the time, my knowledge of Roseland Dance City’s deep roots in New York’s Latin music scene was limited. It was, after all, seemingly the domain of older generations, seeking to recapture the nostalgia of bygone eras, a perception reinforced by its proximity to Local 802 of the Musicians Union. Observing the elegantly dressed seniors queuing, eager to enter their dance sanctuary, felt worlds away from the rock and roll nights of my own generation. Yet, an undeniable curiosity lingered, perhaps fueled by the echoes of film noir that Roseland Dance City evoked, reminiscent of smoky backrooms and clandestine rendezvous I’d seen on screen.

Initially, Roseland Dance City brought to mind Harlem’s legendary Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn, venues catering to white audiences, or even the romanticized “Rick’s Café Américain” from Casablanca, a melting pot of intrigue. Hollywood’s cinematic imagery has a way of embedding itself in our minds. However, once inside Dance City, as it was also known, I realized it transcended these fictional portrayals. Roseland Dance City was a sophisticated ballroom, a far cry from the juke joints of the past. Just a decade prior, I’d stood in lines myself, outside iconic music theaters like the Brooklyn Paramount, Academy of Music, the Brooklyn Fox, and Harlem’s Apollo Theater – but not for dancing. Those were temples of doo-wop, showcasing R&B vocal groups that defined my generation’s sound during Allan Freed and Murray The K’s rock ‘n’ roll extravaganzas. But even this phenomenon had its precursors, all woven into the rich tapestry of American dance history, and Roseland Dance City was a key thread in that weave.

Swing Jazz: Charting the Course of American Dance Floors

Legend has it that the United States’ first “nightclub” emerged in New Orleans in 1912, aptly named “The Cave” and nestled in the Roosevelt Hotel’s basement. Before this, from 1900 to 1920, working-class Americans flocked to honky-tonks and juke joints, dancing to solo piano or small “territory bands” whose music pulsed from jukeboxes. These territory bands, the unsung heroes of dance, traversed the American landscape, playing nightly at venues like VFW Halls, Elks Clubs, and hotel ballrooms. Prohibition ushered nightclubs into the shadows as speakeasies, and within this era, jazz began to solidify. Black communities, dancing to the rhythms of their time, embraced the Charleston and the Lindy Hop. The Charleston, named for Charleston, South Carolina, gained mainstream popularity with James P. Johnson’s 1923 hit “The Charleston.” The Lindy Hop’s origin story is equally colorful: a dancer nicknamed “Shorty,” observing couples at a club, was asked by a reporter about the dance style. Spotting a newspaper headline about Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight, “Lindy Hops The Atlantic,” Shorty reportedly replied, “Lindy Hop.” Whether apocryphal or not, the name stuck, and the Lindy Hop was born.

A pivotal moment arrived on March 26, 1926, in New York City, reshaping jazz history. The Savoy Ballroom, opening its doors on Lenox Avenue in Harlem, was transformative. Swing jazz dominated opening night, its infectious energy ensuring immediate success. The Savoy boasted an expansive dance floor and a double bandstand. Owned by Moe Gale and managed by Charles Buchanan, the Savoy quickly became synonymous with swing.

“Swing” captures the Savoy’s essence, but “big” also comes to mind. The atmosphere crackled with energy, fueled by incredible dancers and performances by all the great black jazz bands. The Savoy drew top dancers from across New York, both black and white. With the end of Prohibition in 1933, the nightclub scene revived. New York’s Stork Club, El Morocco, and the Copacabana featured live big bands dedicated to dance music, but the Savoy remained the most popular. The Savoy participated in the 1939 World’s Fair with “The Evolution of Negro Dance” and was immortalized in “Stompin’ At The Savoy” (1934). Herbert White, the head bouncer, formed “Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers,” a dance troupe featured in films like “A Day at the Races” and “Hellzapoppin’.” This elite group shaped swing dance, influencing social dance in the US, Europe, Australia, Latin America, and parts of Africa. Early mambo dancers in Mexico City cited the Lindy Hop and jitterbug as influences on their choreography, enhancing Cuban son and danzón with borrowed moves.

The Savoy Ballroom – Harlem, New York CityThe Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, New York City, a legendary dance venue that rivaled Roseland Dance City in its impact on dance history.

The Savoy Ballroom – Harlem, New York CityThe Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, New York City, a legendary dance venue that rivaled Roseland Dance City in its impact on dance history.

Cab Calloway introduced a Lindy Hop variant, the jitterbug, named after his 1934 tune. Mainstream America (primarily white audiences) embraced these dances, creating a snowball effect. Every ethnic community adopted black dances, tap, and jazz. Benny Goodman spearheaded the swing era, even inspiring “country swing.”

Transculturation and Adaptation: New Orleans, Hollywood, Paris, and New York’s Intertwined Dance History

Simultaneously, Dean Collins, a Jewish dancer, mastered black dance styles. Growing up in Newark, New Jersey, he danced at the Savoy by 13 and was named “Dancer of the Year” by The New Yorker in 1935. Arriving in Hollywood in 1938, he danced in or choreographed over 100 films (1941-1960), showcasing California’s white dancers performing Lindy Hop, jitterbug, and swing. Throughout the 1940s, these terms were used interchangeably in media to describe this dance style. However, in 1938, Donald Grant, president of the Dance Teachers’ Business Association, dismissed swing as “a degenerate form of jazz,” blaming economic instability for its popularity.

During World War II, swing jazz and the jitterbug were banned in Nazi-occupied France for their “decadent” American influence. This music went underground to discothèques, basement clubs where DJs played hot jazz on turntables when jukeboxes weren’t available. “Latin” music was also restricted, but to a lesser extent, not being categorized as “degenerate art” like African-based music, which was associated with Jews, communists, and anything deemed dangerous to the “master race.”

Back in the US, dance instructors recognized the jitterbug’s growing popularity. Dance schools like the New York Society of Teachers and Arthur Murray Studios began documenting and teaching African-based dances in the early 1940s. Previously, they focused on European dances like the quickstep and waltz, with some fox-trot and peabody, later adding Latin dances like tango, pasodoble, samba, merengue, mambo, and cha-cha-chá, often overlooking their African roots. Arthur Murray studios adapted to local demographics, teaching different swing styles in different cities. Lauré Haile, a swing dancer, named the white community’s style “Western Swing.” Dean Collins taught Arthur Murray teachers in Hollywood and San Francisco in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

In 1953 Paris, Régine Zylberberg, “Régine, Queen of the Night,” at her “Whisky À Go Go” nightclub (founded in 1947), installed a dance floor, colored lights, and replaced the jukebox with turntables, creating the modern discotheque.

Dancers at the “Whisky À Go Go” nightclubDancers enjoying the atmosphere at the “Whisky À Go Go” nightclub in Paris, a precursor to the modern discotheque and a world away from the grand ballrooms like Roseland Dance City.

Dancers at the “Whisky À Go Go” nightclubDancers enjoying the atmosphere at the “Whisky À Go Go” nightclub in Paris, a precursor to the modern discotheque and a world away from the grand ballrooms like Roseland Dance City.

Post-WWII, an economic boom emerged in the US, with New York as the global leader. Returning soldiers continued jitterbugging to country and western music in bars. The Savoy Ballroom closed in 1958 and was demolished. The 1960s brought race riots and population shifts to New York. Industries declined, and corporations moved out. However, service industries grew, and New York remained a cultural and commercial hub with a vibrant music scene.

In the early 1960s, Annabel’s discothèque opened in London. In 1962, New York’s Peppermint Lounge became a hotspot, known for go-go dancing. Joey Dee and The Starlighters’ film “Hey Let’s Twist” popularized the club. Dance scenes were evolving, but Roseland Dance City remained resistant to these trends, maintaining its traditional ballroom dance focus.

America’s Hit Parade: A Land of Shifting Dance Trends

By 1960, the baby boom generation became teenagers and young adults, seeking their own identity. Changes swept across education, values, lifestyles, and entertainment. The 1960s were a period of musical and dance revolution, with new dance fads emerging constantly, often commercialized versions of steps created by Afro-American dancers in clubs and discothèques. “Dancemanias” swept the world, introducing dances like the Madison, Swim, Mashed Potatoes, Twist, Frug, Watusi, Shake, Hitchhike, Pony, Dog, and Chicken. These were individual dances, marking a shift away from partner dancing. For a brief time, the Cuban Pachanga gained youth popularity. Ray Barretto’s “El Watusi” (1962) topped charts in 1963, attracting non-Hispanic audiences. Latin music gained crossover appeal, engaging young Hispanic-Americans.

Meanwhile, older generations still enjoyed mambo, bolero, and tango, embracing partner dances. By 1965, Cuban dance music, or “Latin” music, became increasingly popular. However, it would be another decade before ballrooms like Roseland Dance City truly captured my attention. My generation favored bars and taverns, while Latin youth flocked to marathon dances at venues like the Manhattan Center and Hunts Point Palace. The Palladium Ballroom closed in 1966, and my visits were limited to its final two years, more focused on the bands than dancing. Discothèques only gained my interest in the mid-1970s.

The 1970s saw social activism and urban challenges in New York. By mid-decade, the city was perceived as crime-ridden. In 1975, bankruptcy was narrowly avoided. 1977 brought the Great Blackout and the Son of Sam killings.

Roseland Dance City, however, remained a haven for an older, largely non-Hispanic clientele who cherished Latin dances. Many were regulars since the 1940s, participating in the Harvest Moon Ball Dance Championships at Madison Square Garden from 1930 to 1984, an “amateur” competition sponsored by the Daily News.

1927: Dance Fever Grips New York City

An unofficial dance contest in Central Park in 1927 drew 75,000 spectators, leading future contests to Madison Square Garden for safety. A 1934 attempt was shut down by City Hall. The official Harvest Moon Ball started in 1935 at Madison Square Garden. In 1938, it included Lindy Hop and jitterbug, captured in newsreels from 1938 to 1951.

Preliminaries began in August in clubs and ballrooms across the city, with Roseland Dance City as a key venue. Preliminaries had three judges, finals had five. Divisions included conga, Lindy Hop, rhumba, jitterbug, foxtrot, tango, and later mambo, cha-cha-chá, and hustle. An “All Around Champion” was also crowned.

Ed Sullivan emceed early contests. The event grew, inspiring similar balls in Chicago and Los Angeles, becoming the world’s most famous dance contest until 1980, and continuing until 1984 under past winners’ sponsorship. The theme song was “Shine On, Harvest Moon.” Music was provided by top musicians like Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman, Machito, and the house band led by Ramón Argüeso, featuring vocalist Raúl Azpiazu and Panamanian pianist Terry Pearce. I had the pleasure of singing with Argüeso’s band under Pearce’s direction. Years later, I reconnected with Pearce at the Allegria Hotel in Long Beach, NY, where he still played at 77.

Panamanian Jazz Artist Terry PearcePanamanian Jazz Artist Terry Pearce, a key figure in Roseland Dance City’s history and a link to its golden era of Latin music.

Panamanian Jazz Artist Terry PearcePanamanian Jazz Artist Terry Pearce, a key figure in Roseland Dance City’s history and a link to its golden era of Latin music.

Déjà Vu: Remembering a Panamanian Music Master

Pianist Terry Pearce, a Roseland Dance City regular, fondly recalled his time with Argüeso.

TERRY: “I played at Roseland Dance City from 1974 to 1988, first with Argüeso and then with my own band. We played daily and for events like the Harvest Moon Ball. We even had a cameo in the movie “Roseland”. After Argüeso’s death in 1996, I led the band, reduced to eight pieces, billed as the Terry Pearce Orchestra, until 2001. We played Latin dances and swing.”

Pearce, born in Colón, Panama, on August 10, 1933, was encouraged by his mother, Savina, to study music. By twelve, he played in local Cuban music groups.

CHICO: “Terry, tell me about your early days in Panama. Were your groups like Cuban sextetos?”

TERRY: “Very much so. We used marímbula instead of bass initially, then guitar, bongó, tumbadoras, and trumpets. We played ‘bien típico,’ mostly at private parties and carnivals. I played with ‘el viejo’ Edgehill, a great bassist, and later with Armando Boza’s seventeen-piece band at seventeen. Mauricio Smith and Víctor “Vitín” Paz were also in that band, later becoming Latin jazz legends in New York, working with Machito and Tito Rodríguez.”

CHICO: “Do you remember the year?”

TERRY: “1951. I was in high school but toured Panama with Armando’s band, playing in hotels for tourists and locals. In 1955, we went to Ecuador to play at the Bagatelle Hotel in Quito for six months, playing Cuban music and Panamanian cumbias. Beny Moré was popular then, and I played with him twice during Carnaval in Colón and Panama City. I admired his pianist ‘Peruchín’ Justiz.”

CHICO: “I know Beny first went to Panama with Pérez Prado in 1949, and again in 1955 and 1958. Peruchín might have replaced his pianist ‘Cabrerita’ on those trips.”

TERRY: “Peruchín was already in Panama then. He was one of Cuba’s greatest pianists, rhythmically innovative, practically inventing the guajeo. He was also a great arranger, joining Orquesta Riverside and later Beny’s big band. He recorded with Chico O’Farrill and Cachao, and led his own quintet. He died in 1977. Armando’s band was very influenced by Cuban music; it was our specialty.”

CHICO: “Did you play Panamanian music too?”

TERRY: “Yes, especially in Los Santos, famous for carnivals and festivals like the Festival Nacional de la Pollera.”

CHICO: “Panama has beautiful traditions, like the Spanish Caribbean. Its US connection is strong, especially in music. Panama has a long jazz history. By the 1940s, Colón had ten jazz orchestras. Jazz legends from Panama include Víctor Boa, Clarence Martin, Barbara Wilson, Billy Cobham, Mauricio Smith, Carlos Garnett, and John McKindo. Danilo Pérez revitalized this legacy with the Panamanian Jazz Festival in 2003.”

TERRY: “Jazz was always present in Panama, thanks to black laborers who built the canal from the US and British West Indies. By 1910, the Panama Canal Company employed over 50,000 workers, mostly black Caribbeans. We formed a community distinct in race, language, and culture. Many migrating to the US, like myself with a name like Pearce, experienced a duality.”

CHICO: “How did you come to play Latin dance music in the US, at places like Roseland Dance City?”

TERRY: “In 1960, I left Armando Boza and worked cruise ships, very lucrative then. The Evangelina Quartet toured the West Indies until 1962 when I got my US visa and moved north.”

CHICO: “How did you feel arriving in America?”

TERRY: “Great! I arrived at Penn Station, New York, on January 20, 1962.”

CHICO: “Who gave you your first break?”

TERRY: “Trumpeter Bobby Woodland. He helped me get my musician’s card and work union halls and hotels. I worked Fridays with him at summer resorts in upstate NY, like The Raleigh and The Pines, billed as Bobby Madera, playing dance music. I was comfortable with Afro-Cuban rhythms. But I wanted to play everything. In ’62, trumpeter Doc Cheatham hired me at Jack Silverman’s International Cabaret in downtown Manhattan for swing jazz. I worked with Cheatham and Woodland from ’62 to ’69, and also with Willie Bobo at Birdland on Mondays. Cheatham often took me to the Palladium. Machito’s band respected him.”

CHICO: “Anyone else we should know about?”

TERRY: “I substituted for René Hernández with Machito at the Palladium and St. George Hotel when he was ill. In ’69, I played at the Eden Roc Hotel in Miami with Chubby Checker, directed by Mauricio Smith. We also played the President Hotel in Atlantic City and RDA in Philadelphia. New dances were constantly emerging, and Chubby was at his peak. The sixties were good to me.”

CHICO: “Dance music kept you busy, but it wasn’t just about dance floors, was it?”

TERRY: “No, I played serious music too. After Chubby, Mauricio and I played jazz with Latin hints at Ali Baba East and Carlton Terrace, using a Hammond organ. Nell Carter would jam with us after her Broadway shows. We played there until 1974. But dance was steadier work. I briefly returned to the Catskills with Billy Ford and the Thunderbirds, then worked with Mauricio at The Rainbow Room with bassist Víctor Venegas.”

CHICO: “What about charanga bands?”

TERRY: “Frank Mercado connected me with José Fajardo’s charanga band for gigs. I also worked with Lou Perez occasionally. Charanga was popular. Work was plentiful, and people danced. But Argüeso was the hardest working bandleader. With Ramón, I always had steady work at Roseland Dance City.”

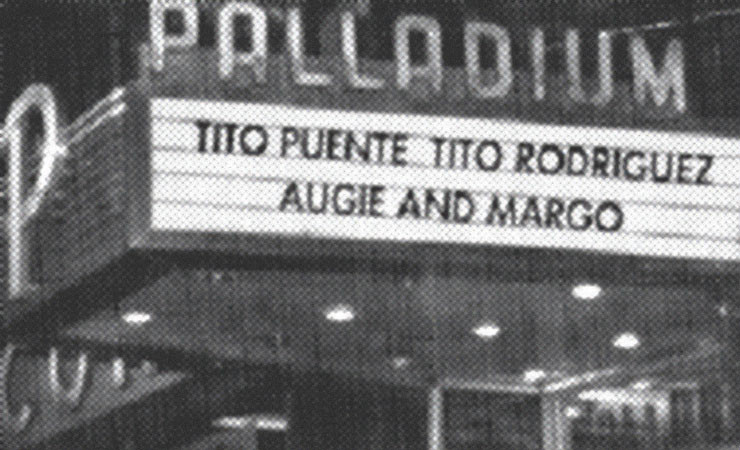

Palladium Ballroom Marquee – New York CityPalladium Ballroom Marquee in New York City, a rival venue to Roseland Dance City in the Latin music scene.

Palladium Ballroom Marquee – New York CityPalladium Ballroom Marquee in New York City, a rival venue to Roseland Dance City in the Latin music scene.

Vaya Means Go!: The Latin Takeover of Manhattan Dance Scene

In 1952, Roseland Dance City and Arcadia Dance Hall were still popular for classic American dance music. However, for the younger, hipper crowd, the Palladium Ballroom reigned supreme. Dancing on 2 and in clave was essential. It was the place where wild Cuban rhythms dominated. Pérez Prado’s “Mambo No. 5” became a sensation, crowning mambo “king of all dances.” The former Alma Dance Studio became the “home of mambo.” While other clubs like the Caborojeño and Havana-Madrid existed, none matched the Palladium’s popularity. Near Roseland Dance City and Birdland, it was in the urban center. At its peak, it attracted Hollywood and Broadway stars. Wednesday nights featured free dance lessons by instructors like Killer Joe Piro and Carmen Marie Padilla. The Palladium proclaimed itself the “temple of mambo,” and Hollywood capitalized on the craze. Piro danced mambo in the 1950 Universal short “Mambo Madness.” Much has been written about this era and venue, but the late 60s and early 70s brought radical change, impacting dance music. The Palladium closed on May 1, 1966.

A new dance and style, salsa, mambo’s cousin, emerged, becoming “queen of all rhythms.” I asked Terry about the post-mambo dance scene in New York after the Palladium era, outside of Roseland Dance City.

CHICO: “Terry, what do you remember about the 70s dance scene, besides Roseland?”

TERRY: “There were still clubs like Ipanema, Corso, and Casablanca, but the atmosphere changed by 1975. Each club had its own crowd. Discothèques replaced ballrooms, and disco became the craze. Studio 54, opening in ’77 near Roseland Dance City, became very popular, taking business away. Live musicians were becoming obsolete in favor of DJs and recorded music, hurting musicians, including Latin musicians. When I started at Roseland Dance City with Argüeso, we played six nights a week, then less and less. Eventually, we were down to Sundays. Maybe it was the clientele.”

CHICO: “You’re right. Roseland Dance City initially had a ‘whites only’ policy, billed as ‘home of refined dancing,’ and remained somewhat segregated, unlike the Palladium. Roseland Dance City was famous for big bands like Glenn Miller and innovative dance contests. But music eventually brought people together. Black dances like the jitterbug were heard at Roseland Dance City. Count Basie’s appearance was a breakthrough.”

“When Louis Brecker sold Roseland Dance City in 1981, new owners introduced ‘disco nights,’ alienating the Latin crowd and changing Roseland Dance City’s image. Sundays remained for the older crowd, becoming a nostalgic haven for seniors. Young Latinos stopped going. Disco had unintentionally killed the Latin scene at Roseland Dance City. The Sunday crowd was aristocratic. By the time I played with your band, Roseland Dance City felt like a nursing home, a time warp. My only consolation was playing with stellar musicians like you, Frankie Colón, and others.”

TERRY: “Those were good times despite the smaller crowds. They’ll never return.”

CHICO: “In 1974, Brecker said Roseland Dance City was about ‘cheek-to-cheek dancing.’ But that changed when Phil Peters became the first Latin promoter to rent Roseland Dance City for events, attracting a younger crowd. His Women’s Liberation Dance was successful. Peters had an ‘exclusive’ contract to be the only Latin promoter, leading to the Miguelito Valdés tribute. That night, Roseland Dance City saw a diverse crowd, a rainbow of people, including a growing African and Asian presence alongside the Anglo and Latino regulars.”

Roseland Ballroom Marquee – New York CityRoseland Ballroom Marquee in New York City, a landmark sign for Roseland Dance City, beckoning dancers for decades.

Roseland Ballroom Marquee – New York CityRoseland Ballroom Marquee in New York City, a landmark sign for Roseland Dance City, beckoning dancers for decades.

Try the Impossible: New Age Fusion and Confusion

Despite social and musical shifts, 1977 was a vibrant year for music, including funk, disco, rock, jazz fusion, reggae, and hip hop. Salsa remained dominant in New York City, with merengue close behind.

The film “Roseland” was released in ’77, directed by James Ivory. However, it focused on waltz, hustle, and peabody, not resonating with me or young Hispanics. The episodic film, unified by vintage hits, told stories of dancers seeking partners. “Our Latin Thing,” a 1972 documentary by Leon Gast, better captured the urban Latino experience, filmed at the Cheetah and in Hispanic neighborhoods. It opened with Ray Barretto’s “Cocinando,” a Cuban tune presented as something new, showcasing neighborhood kids jamming on percussion, a groove that eclipsed ballroom dancing.

Interestingly, decades after salsa’s peak, older dancers continued enjoying mambo, cha-cha-chá, Lindy Hop, jitterbug, and swing jazz, keeping the spirit of Roseland Dance City’s traditional dances alive.

And Roseland Dance City itself? It still stood, its purpose evolving.

Epilogue

By 1980, mambo/salsa dancers lost venues, leading to smaller clubs and fewer live bands. “Latin” music changed. The Marielitos brought new Cuban sounds, hinting at timba. In 1984, a shooting occurred at Roseland Dance City. In 1990, suspects in a tourist’s subway murder were found partying there. “Disco nights” ended, and redevelopment concerns arose. In 1996, new owner Laurence Ginsburg planned to replace Roseland Dance City with an apartment building, citing earthquake codes. Renovations occurred, but demolition remains a possibility. Roseland Dance City hosted Hillary Clinton’s birthday party and rock artists like Madonna, but for Latin New Yorkers, the Miguelito Valdés tribute remains most memorable. That night, “Latin” music as they knew it was nearing its end.

Coda

I asked Terry his opinion on salsa.

TERRY: “Chico, I love salsa, it’s like what I played in Panama – son montuno and mambo. Arrangements and messages change, but the foundation remains. “

CHICO: “What about rap and reggaeton?”

TERRY: “I don’t like to put anyone down, but I can’t get into it. It’s a degeneration of music. These artists don’t use real musicians; it’s electronically made in studios, without charts. How can they reproduce it live? They can’t. It sounds like scraping the bottom of the barrel. Maybe it’s time to start again, creating music, not just sounds.”

Roseland Ballroom – New York CityRoseland Ballroom in New York City, a historic venue known as Roseland Dance City, representing a legacy of dance and music.

Roseland Ballroom – New York CityRoseland Ballroom in New York City, a historic venue known as Roseland Dance City, representing a legacy of dance and music.

About Terry Pearce

Terry Leopold Pearce (1933-2022), born in Colón, Panama, was a pianist from age 12. At 17, he joined Armando Boza’s band, later working on cruise ships. He emigrated to New York in 1962, playing with Chubby Checker and Frankie Lymon. He joined Roseland Dance City, leading its Latin band as the Terry Pearce Orchestra. He also ran a trucking business, TLP Transportation, retiring in 2002 to focus on music. His last performances were before the pandemic. He passed away on November 16, 2022, leaving behind a rich legacy tied to the history of Roseland Dance City and Latin music in New York.