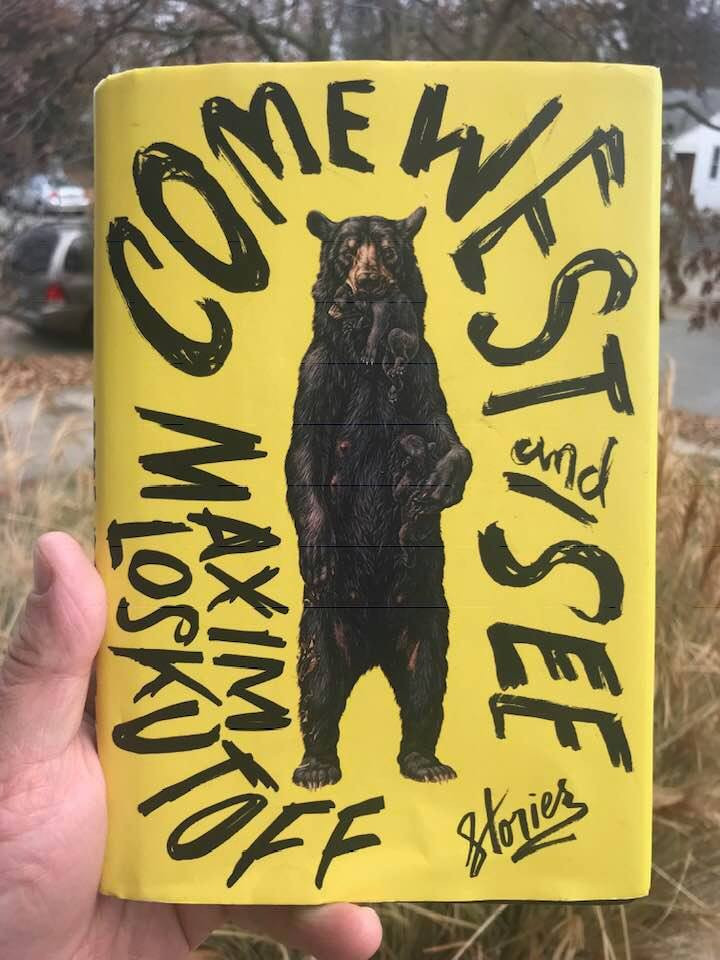

Maxim Loskutoff’s debut collection, Come West and See, has garnered significant attention, and for good reason. Within its pages, readers are transported to the rugged landscapes of the American West, encountering stories that delve into the complex relationship between humanity and nature. Among these compelling narratives, “The Dancing Bear” stands out, not just for its evocative title, but for its exploration of primal desires and the untamed wilderness. This introductory story, acting as a prologue to the collection, immediately sets the stage for Loskutoff’s overarching themes, drawing readers into a world where the lines between human and animal, civilization and wilderness, become blurred. At the heart of this story is a memorable image: a “Naked Dancing Bear,” a phrase that encapsulates the story’s strange beauty and underlying tensions.

“The Dancing Bear” introduces us to Bill, a solitary trapper living in the Montana Territory of 1893. Content in his self-sufficient life, Bill’s routine is disrupted by the arrival of a magnificent eight-foot female grizzly bear drawn to the apple tree outside his cabin. Loskutoff paints a vivid picture of this creature, emphasizing its grace and power as it rears up on its hind legs to reach the highest apples, reminding Bill of a “dancing bear” he once witnessed in a sideshow. This initial appreciation for the bear’s majestic presence soon evolves into something more complex and unexpected.

As Bill observes the bear in its natural element, a peculiar transformation occurs within him. Standing naked in his doorway, he finds himself not just admiring the animal, but experiencing a stirring of arousal. This pivotal moment, where human desire intertwines with the raw beauty of the wild, is central to understanding the story. The “naked” aspect of this encounter is twofold: Bill’s literal nudity underscores his vulnerability and primal state, mirroring the untamed nature of the bear. It’s in this vulnerable state, witnessing the bear’s natural, uninhibited feasting, that Bill’s own desires are awakened. These encounters become a ritual for Bill, a time for self-gratification fueled by the powerful image of the bear.

47093196_10106207474134080_8094921658172702720_n

47093196_10106207474134080_8094921658172702720_n

A majestic grizzly bear, the “naked dancing bear” of the story, stands tall amidst an apple tree, embodying the untamed wilderness that stirs complex emotions within the protagonist, Bill.

The departure of the grizzly bear for hibernation plunges Bill back into loneliness, highlighting his profound isolation. His attempts to replace the bear’s presence with piles of animal furs only underscore the emptiness he feels. This loneliness drives him to Missoula, seeking human connection in a brothel run by Bad Lucy. His past experience with rejection from a woman he wished to bring back to his solitary cabin reveals a pattern of isolation rooted in his inability to connect with human intimacy in a conventional way. His brothel visit is short-lived, ending abruptly when he finds the hired woman lacks the “hirsute” quality he has become accustomed to, a clear indication of how deeply the bear has imprinted on his desires. This failed attempt at human connection further emphasizes the bear’s unique hold on his psyche.

The narrative then fast-forwards to March, marking the bear’s return, but this time with a cub. This development introduces a new layer of complexity to Bill’s unconventional infatuation. The challenges presented by a mother bear and her offspring, which the original blog post hints at, are left for readers to discover in Loskutoff’s story. However, even without revealing the ending, it’s clear that “The Dancing Bear” is not simply a quirky tale of a man and a bear. It serves as a powerful allegory for humanity’s complicated relationship with the natural world.

Loskutoff masterfully uses “The Dancing Bear” to introduce the broader themes explored throughout Come West and See. The story delves into the tenuous balance between appreciation and exploitation of nature. Bill’s initial admiration for the “naked dancing bear” quickly morphs into a self-serving desire, blurring the lines between respecting the animal and objectifying it. This mirrors a larger commentary on human actions in the wild – we may appreciate the beauty of nature, but often our interactions are driven by self-interest, sometimes to the detriment of the very wilderness we admire. The story subtly questions whether our actions, even seemingly harmless ones like feeding wild animals, are truly benign or if they ultimately disrupt the natural order.

The concept of the “naked dancing bear” becomes a potent symbol within this context. It represents the raw, untamed beauty of nature that can both attract and challenge humanity. The “nakedness” suggests vulnerability and authenticity, while the “dancing” implies a fluid, dynamic energy that is inherently wild and unpredictable. Loskutoff’s prose, rich in detail and evocative imagery, further enhances this exploration, painting a vivid picture of the Montana landscape and the inner landscape of a man grappling with loneliness and desire.

In conclusion, “The Dancing Bear” is more than just an intriguing title; it’s a gateway into Maxim Loskutoff’s compelling collection Come West and See. The story’s exploration of a man’s unusual fascination with a grizzly bear, the “naked dancing bear,” serves as a powerful and thought-provoking introduction to the book’s overarching themes. Loskutoff’s work is a significant contribution to contemporary nature writing, offering readers a journey into the heart of the American West and the complex relationship between humans and the wild. Come West and See is highly recommended for anyone seeking fiction that is both entertaining and deeply insightful, prompting reflection on our place in the natural world and the often-unacknowledged primal desires that shape our interactions with it.