Last November, a notable book landed, America Dancing: from the Cakewalk to the Moonwalk, authored by Megan Pugh, a graduate of Yale University. This insightful work reinterprets American dance history, delving into pivotal moments of artistic evolution with both flair and profound understanding. Pugh’s writing style is captivating, reflecting a nation’s quest for identity through movement.

Acclaimed dance critic Alastair Macaulay of The New York Times lauded America Dancing as “valuable, original, refreshing, wide-ranging, mind-opening,” also praising Pugh’s “dazzle” of knowledge and vivid writing. Similarly, the Boston Globe highlighted Pugh’s skillful analysis in capturing dance nuances, acknowledging her depth as a critic attuned to the layered meanings within dance performances and histories.

Megan Pugh, a poet and scholar of American literature and culture, currently imparts her knowledge at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Oregon. She graciously shared her insights in an email exchange with Scott Saul, Professor of English.

Scott Saul: Your book, brimming with energy, starts with a poignant 1939 narrative: the arrest of Black tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in Times Square. He was charged with “disorderly conduct” for resisting a white policeman’s order to move, as Robinson was admiring a neon sign of himself advertising his Broadway show. Why did you choose this somber yet compelling beginning for your exploration of American dance and “Megan Dance” history, highlighting the contrast between Black performers on stage and Black individuals in public spaces?

Megan Pugh: This anecdote resonated deeply as I considered it further. Bill Robinson, a master of tap dance, embodied personal power and freedom through his movements. He commanded space and sound, innovating rhythms with poise and dignity. Known for his assertiveness, he challenged racist hecklers and, in this instance, confronted the officer who arrested him. Yet, his black identity in a racially biased nation rendered him vulnerable.

While discussions on American movement often emphasize freedom and individualism, which holds some truth, I aimed to address the limitations imposed on movement in this country, particularly for non-white individuals. The artistry and impact of dance performances cannot be fully appreciated without acknowledging the historical contexts that shape them—histories that performances may attempt to reveal, defy, mend, or reimagine.

The 1939 incident poignantly spatializes these concepts. Robinson’s neon sign image, high above, portrays him as an emperor, yet this elevated representation is overshadowed by the street-level reality. Throughout the book, I sought to maintain both perspectives, examining the multifaceted nature of American dance and its socio-political context.

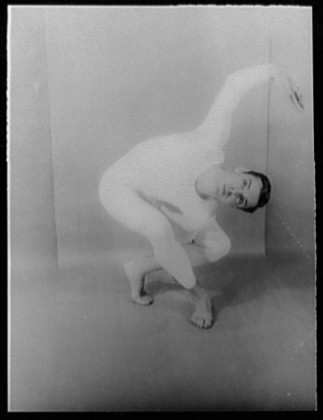

PughFig5.2

PughFig5.2

Image alt text: Choreographer Paul Taylor in a striking black and white portrait by Carl Van Vechten, highlighting a key figure in American modern dance discussed in Megan Pugh’s book on American dance history.

SS: Dance, with its fluid expression and reliance on bodily language, is notoriously challenging to articulate in words. You’ve been widely praised for your ability to do so effectively. Do you believe your background in poetry—both in reading and writing—influenced your prose in capturing the essence of “megan dance” and movement?

MP: Growing up with a mother who founded a ballet company immersed me in dance and dance discourse from a young age. I recall instructors using vivid metaphors to guide our movements—imagining shining stars on our sternums for posture or inverted ice cream cones in our arms for graceful arm movements. Metaphor is indeed powerful! This is often cited as why poets excel as dance critics, with Edwin Denby being a prime example. However, the connection extends beyond metaphor. Gestures, like poetic language, can hold multiple layers of meaning. Poets are adept at navigating the boundary between the ineffable and what can be expressed through language. Writing about dance necessitates working within this very liminal space.

T. S. Eliot’s description of a poet’s mind, where “disparate experience” coalesces into “new wholes,” resonates deeply. Poets not only perceive connections but utilize them to construct novel entities that resist simple interpretation. Poems, akin to dances, are dynamic and in motion.

Therefore, poetry profoundly shapes my thinking and writing, influencing both descriptive prose and my approach to cultural history. Archival research becomes an act of listening for echoes, patterns, and connections. The task then is to decipher the relationships between these elements. The outcome, while rooted in historical argumentation, mirrors the associative and interpretive processes inherent in poetry.

SS: Were there specific writers—dance critics, cultural historians, or prose stylists—who inspired you in translating “megan dance” and performance into written form? What key lessons did you learn about analyzing dance critically through writing?

MP: I must first acknowledge the formative influence of the “Formation of American Culture” course taught by Jean-Christophe Agnew and Michael Denning at Yale. Their ability to seamlessly integrate labor history, song, policy, and literature within a single lecture was transformative. This capacious approach, where “disparate experience” formed “new wholes,” revealed the expansive possibilities within academia, specifically in American Studies.

Regarding individual writers, I have drawn immense inspiration from scholars like Daphne Brooks, Brenda Dixon-Gottschild, Elizabeth Dillon, Joel Dinerstein, W. T. Lhamon, Eric Lott, Jacqui Malone, and Joseph Roach, among many others. Critics such as Deborah Jowitt, Manny Farber, Luc Sante, Ralph Ellison, and Joan Didion have also been profoundly influential. Greil Marcus stands out as a particularly generous and impactful mentor.

However, limiting influences to critical writing feels incomplete. “Creative” writers—Ishmael Reed, Charles Chesnutt, Nella Larsen, and Caryl Phillips—have contributed significantly to discussions on race and performance. Poets like Susan Howe, Robyn Schiff, M. NourbeSe Philip, and C. D. Wright explore themes of historical persistence and disruption. Choreographers Agnes de Mille and Paul Taylor, subjects in my book, are also exceptional writers in their own right.

Pughfig1.1 (Megan Pugh

Pughfig1.1 (Megan Pugh

Image alt text: A vintage photograph circa 1897 from the Library of Congress, showcasing dancers performing the cakewalk, an early and significant American dance form, relevant to Megan Pugh’s historical analysis of American dance.

SS: On a personal note, you achieved the remarkable feat of publishing your book in a remarkably short timeframe, just three years after your dissertation, and while raising a young child. What advice can you offer to those striving for work-life balance, especially within academia?

MP: I’m uncertain if I’ve truly achieved “balance,” but parenthood has certainly made me a more efficient writer. During my son’s first year, my writing time was limited to a few mornings a week at the library. These hours became invaluable; leaving my child and incurring babysitting costs, coupled with a pre-birth book contract and deadline, made writer’s block an unaffordable indulgence. Having the project’s framework and chapter drafts already in place was beneficial, as much of the conceptual work preceded sleep deprivation.

I also acknowledge the privilege of having a partner whose stable employment provides essential family support, including healthcare, mitigating the financial risks of my adjunct professorship at Lewis and Clark. While tenure-track security would be welcome, the flexibility of part-time work is also advantageous, allowing me significant time with my son. I recognize my fortunate position within a challenging academic job market, particularly for humanities PhDs focusing outside traditional literary topics. Yet, I pursued the book I wanted to write, live in a city we love, enjoy teaching, and cherish time with my son. Whether this qualifies me to give advice is debatable. I do, however, offer a strong cautionary perspective to students considering humanities graduate studies, while still affirming the profound value of my own graduate experience at Berkeley.

SS: I understand you’re collaborating with fellow Berkeley English PhD graduate Gillian Osborne on a series of baseball poems. With the baseball season underway, could you share a poem to set the tone?

MP: I wish I could offer a new poem, but my contribution to Gillian is overdue, highlighting the ongoing challenge of balancing parenting and writing! Instead, I can share links to selections from our project published in Cobalt and Boom: A Journal of California. Our poem exchange began after witnessing Matt Cain’s perfect game in 2012. Structured like a baseball game and epistolary in nature, the poems explore themes of place, gender, family, fandom, and camaraderie. My innings, at least, often reveal a surprising amount of sentimentality in baseball.