The Matachines Dance, a captivating and enigmatic performance, bridges cultures and centuries. I was fortunate to witness this ritualistic reenactment on Christmas Eve at the Pueblo of Okay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo), an experience that sparked a deep dive into the dance’s rich tapestry of meaning. Performed during significant feast days in both winter and summer within Pueblo Indian and Hispano communities across the Rio Grande Valley and beyond, the Matachines Dance exists in a remarkable diversity of forms – at least 44 known versions! This unique cultural phenomenon deserves exploration to understand its enduring appeal and complex symbolism.

Delving into the Core Elements of the Matachines Dance

At its heart, the Matachines Dance, particularly in New Mexico, embodies a symbolic struggle between opposing forces – light and dark. This dramatic conflict culminates in a transformative sequence involving key figures: a young maiden representing purity, a powerful bull, the mischievous Abuelos (grandfathers or tricksters), or sometimes clowns, and two lines of masked dancers who evoke the imagery of soldiers. The presence of the Abuelos adds an element of unpredictability, with one often wielding a whip and the other occasionally appearing as a playful transvestite, blurring traditional gender roles within the ritual.

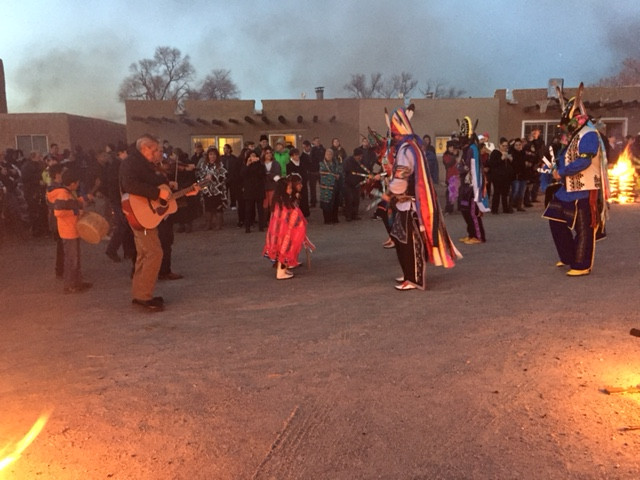

Matachines dancers in vibrant regalia, adorned with ribbons, performing at dusk in Okay Owingeh Pueblo, New Mexico.

Matachines dancers in vibrant regalia, adorned with ribbons, performing at dusk in Okay Owingeh Pueblo, New Mexico.

The climax of the dance centers on the maiden’s confrontation with the bull. In a powerful symbolic act, the bull is overpowered, representing a ritualistic sacrifice through castration and death. His scattered seed is then cast into the audience, signifying fertility and renewal. Only after this sacrifice does the Ogress, traditionally played by a man, dramatically collapse and “give birth” to a newborn Abuelito, embodying the spirit of the dance reborn for the coming year.

A Dance of Contrasts: Festive Attire and Solemn Undertones

The Matachines Dance is a spectacle of visual richness. Dancers are adorned in elaborate costumes, vibrant with a kaleidoscope of ribbons that flow gracefully with their movements. Attention to detail is paramount, evident in the intricate beadwork of armbands, the rhythmic rattles, and the palmas or tridents carried by the masked figures. Magnificent beaded moccasins ground the dancers, while elaborate headdresses known as cupiles crown their heads.

Yet, beneath this festive exterior lies a profound solemnity. A subtle undercurrent of violence permeates the dance, culminating in the bull’s symbolic death and castration – a stark reminder of sacrifice and transformation. This duality creates a powerful and thought-provoking experience for the observer.

Experiencing the Dance at Okay Owingeh Pueblo

My personal experience of witnessing the Matachines Dance on Christmas Eve at Okay Owingeh Pueblo was deeply moving. As dusk descended, pewter and shark-gray clouds painted the horizon, setting a dramatic stage for the dancers’ emergence from the church. The resonant tolling of the church bell echoed through the plaza, a sound both powerful and ancient. Venus, bright in the twilight sky, seemed to watch over the unfolding ritual.

Farolitos, traditional paper lanterns, and blazing Luminarios – carefully stacked cedar logs – illuminated the area around the church and the plazas, casting flickering shadows and adding to the mystical atmosphere. Crackling fires sent plumes of black smoke and sparks swirling upwards. A single gunshot punctuated the air as the procession moved between plazas, heightening the sense of ritual and drama.

The music, played on guitar and violin, often carried a dissonant, almost foreboding quality, adding to the solemn mood. Amidst the sounds of dancers’ bells and rattles, the chanting of Penitentes – “Santa Maria” – invoked the Virgin Mary in Spanish, their voices weaving through the crowd that moved with the dancers.

Observing the dancers’ regalia up close, I was struck by the familiar yet enigmatic nature of their headdresses. The elaborately jeweled cupiles bore a resemblance to the miters worn by Catholic Bishops, hinting at a possible syncretism of religious symbols. The fringed edges of some headdresses suggested a Moorish European influence, a subtle nod to the complex historical layers woven into the dance. The dancers’ faces were concealed by brightly colored scarves adorned with roses, reminiscent of veils, adding an air of mystery and even a hint of inscrutability to each participant.

A young Malinche and El Toro in the Matachines dance, adorned with traditional attire and face paint, standing in a Pueblo plaza.

A young Malinche and El Toro in the Matachines dance, adorned with traditional attire and face paint, standing in a Pueblo plaza.

My gaze was drawn to a young Native girl, dressed in traditional attire, her cheeks painted with red circles symbolizing purity. She embodied the Malinche figure. Beside her stood the young bull, El Toro, also a child, wearing horns and a hide draped over his back. His eyes, like glowing embers, and the diagonal stripes painted on his cheeks added to his captivating presence.

As the dancers returned to the church for the ritual’s culmination, my friend and I departed, our senses saturated with the experience. A sense of déjà vu lingered, a feeling that I had witnessed this dance before, perhaps in a different context. Later that evening, the memory surfaced: the Matachines dance during Holy Week on the Pasqua Yaqui reservation near Tucson, Arizona, where their role was to banish evil forces during the Deer Dances.

Unraveling the Narrative: Stories and Interpretations

The underlying narrative of the Matachines Dance is multifaceted and open to interpretation. Scholarly perspectives and Pueblo traditions offer various layers of meaning. Some scholars propose the dance signifies a spiritual marriage. Certain Pueblos connect the dance to Montezuma, a Mexican king, sometimes paired with the Virgin Mary, who uniquely remains unmasked in some versions. The Virgin’s communion dress, observed in some performances, further reinforces the idea of a spiritual union between these figures. Another narrative recounts Montezuma, transformed into a bird, flying north to warn the Pueblo people of approaching foreigners, suggesting that mastering the dance would instill respect in these newcomers.

Another interpretation posits the dance as a triumph of good over evil. In this view, the Virgin, often associated with a Christianized Guadalupe and represented by the sole female figure, converts a pagan king to Christianity. However, this interpretation is nuanced by the understanding that Guadalupe is not simply the Virgin Mary, but a complex figure deeply rooted in indigenous Mexican traditions, appearing at the site of the ancient Earth Goddess Tonanztin and embodying a dark-skinned, indigenous identity. The Catholic Church’s adoption of Guadalupe reflects an inability to suppress her powerful presence.

Perhaps, as some scholars suggest, the Matachines Dance narrates the story of Native resistance to Spanish invasion and cultural regeneration in the face of colonial pressures. While the exact timing of the Rio Grande Pueblos incorporating the dance into their ritual calendar remains uncertain, a prevalent theory suggests it signaled a symbolic conversion to Christianity, a plausible explanation given the historical context of colonization.

Intriguingly, some historians have proposed a homoerotic interpretation, viewing it as a celebration of male power. In reality, all these interpretations likely hold validity. The dance’s adaptability, with varying plots across different Pueblos, underscores its capacity to resonate with the specific needs and interpretations of each community at different times.

The Etymology and Evolution of “Matachines”

Even the name “Matachines” is shrouded in intriguing ambiguity. The term first appeared in 16th-century Italy. “Mattaccini” in Italian described unfamiliar and peculiar dances. “Matachines” became the Spanish term for dances performed by captive Indigenous peoples brought to Europe. The name might also stem from an Italian mispronunciation of a Nahuatl word, highlighting the dance’s complex intercultural origins.

Matachines dancers in profile, showcasing their intricate headdresses and ribboned costumes, performing in a Pueblo plaza at night.

Matachines dancers in profile, showcasing their intricate headdresses and ribboned costumes, performing in a Pueblo plaza at night.

Curiously, the “newest” additions to the Matachines Dance – the Malinche, El Toro, and the Abuelos – are central to its current form. Originally, the dance was less narrative-driven, characterized by more intricate steps. While the Matachines Dance was first documented in Bernalillo, New Mexico, in 1530, the precise evolution of its narrative complexity remains a subject of ongoing exploration.

Echoes of Ancient Mythology: A Feminist Perspective

From a feminist and mythological perspective, the “newest” additions to the dance unveil connections to ancient, profound narratives. In Neolithic times (8000-3000 BCE), the Great Mother, in her Virgin aspect – representing wholeness and self-sufficiency, not necessarily sexual purity, and often associated with priestesses – had a consort, sometimes a bull, ritually sacrificed annually to ensure the earth’s fertility and bountiful harvests. The bull’s seed could also regenerate a new king, reigning until his own sacrifice the following year. This archetypal mother-consort drama recurs in ancient myths like Innana and Dumuzi, Cybele and Attis, Isis and Osiris, and even finds echoes in the story of Jesus, a kingly figure sacrificed for humanity’s salvation.

However, with the rise of patriarchal Judaism and later Christianity, the divine feminine was marginalized. Female figures were largely relegated from religious rites as Judeo-Christian traditions supplanted earlier matristic, woman-centered Neolithic beliefs. The Virgin Mary, the epitome of sexual purity, the sorrowful mother, and mediator to a male God, became a diminished vestige of the Great Goddess. Yet, in the Matachines Dance, a resurgence of these ancient themes of sacrifice and transformation emerges. This resurgence, if interpreted correctly, places the Matachines Dance within a broader context, bridging the present with a distant, mythical past that continues to hold profound relevance today.

The Malinche, in this light, can be seen as associated with the Virgin Mary or Guadalupe, but more profoundly, as embodying the Spirit of Woman, encompassing her sexuality, rising from the Earth through an ancient archetypal narrative. Her role in the dance suggests she represents the “hope” for the future. Intriguingly, the Malinche is also connected to lunar cycles and the dawn, mirroring attributes of numerous goddesses throughout history. Perhaps, an “unintended” yet potent meaning of the dance is the reclamation of the lost feminine as a divine force in its own right, offering a life-affirming perspective in ways we are only beginning to comprehend.

A Living, Evolving Tradition

The enduring power of the Matachines Dance lies in its complexity. It transcends mythical, national, and cultural boundaries, as archetypal stories often do. It is a dance rich with layered meanings, constantly evolving, reminding us that innovation and change are inherent to the Matachines tradition. The dance is in perpetual motion, yet deeply rooted in both mythical and historical pasts, shaping its present and future trajectory.

A group of Matachines dancers in full costume, captured from a low angle, performing outdoors during the day.

A group of Matachines dancers in full costume, captured from a low angle, performing outdoors during the day.

The Penitentes, or Brothers of Light, mentioned in the original text, are a significant part of New Mexican religious and social fabric, dating back to the late 1790s. These men dedicate themselves to community care, prayer, and charitable works, further enriching the cultural context surrounding the Matachines Dance.

The Matachines Dance is more than just a performance; it is a living testament to cultural fusion, historical memory, and the enduring power of symbolic expression. It invites us to explore the depths of tradition, the complexities of cultural exchange, and the timeless narratives that continue to resonate across time and cultures.