Li Cunxin, the name synonymous with resilience, passion, and extraordinary talent in the world of ballet, embodies a journey that transcends borders and ideologies. His life story, far from a predictable path, is a captivating narrative of unexpected turns, global recognition, and profound personal evolution. From the depths of poverty in Maoist China to the dazzling heights of international ballet stardom, Li’s experiences are a testament to the transformative power of art and the enduring strength of the human spirit.

This is the story of how a boy from rural China, initially indifferent to the art form, became “Mao’s Last Dancer,” a title echoing both his acclaimed autobiography and the era that shaped his early life. It’s a story of cultural clashes, political standoffs, and the unwavering pursuit of dreams against formidable odds. Beyond the spotlight, Li’s narrative reveals a deeply personal side, marked by the pain of separation, the joy of reunion, the enduring power of love, and a commitment to family that extends to learning a new language for his daughter.

In this exploration of Li Cunxin’s remarkable life, we delve into the pivotal moments that defined his journey. We uncover the accidental discovery that propelled him into the world of ballet, his arduous training, his daring defection to the United States, and his subsequent rise to global ballet prominence. More than just a dancer’s biography, this is an inspiring account of human potential, resilience, and the unexpected beauty that can emerge from the most challenging circumstances.

From Rural Poverty to Beijing Ballet Academy

Born into the stark realities of Maoist China, Li Cunxin’s early life was a world away from the refined elegance of ballet. Poverty was a constant companion, with daily life revolving around the struggle for basic necessities. “We were struggling for food, we had no running water, we didn’t have warm clothes to wear in the bitterly cold winter weather,” Li recounts, painting a vivid picture of his challenging childhood in northeastern China. Survival was the primary focus, a stark contrast to the world of art and culture that would eventually become his domain.

Against this backdrop of hardship, fate intervened in the most unexpected way. At the age of 11, Li’s life took an unforeseen turn when talent scouts from the Beijing Dance Academy arrived at his school. Madame Mao, a ballet enthusiast and the honorary director of the academy, had initiated a nationwide search for young talent. During a seemingly ordinary school assembly, as students sang patriotic songs, these scouts assessed potential candidates. Li’s selection was almost accidental, a moment of serendipity sparked by his observant class teacher.

“My class teacher stopped the last gentleman from leaving said, ‘Excuse me, sir. What about that one?’ And she was pointing at me,” Li recalls, emphasizing the pivotal role of this teacher in altering the course of his life. When he later inquired about why she singled him out, her answer was simple yet profound: his boundless physical energy and restlessness in the classroom suggested a potential aptitude for the physical demands of ballet.

This chance encounter led Li down a path he could never have imagined. He was chosen, along with a select few out of millions, to undergo rigorous ballet training at the Beijing Dance Academy. Leaving his family behind at just 11 years old, Li embarked on a seven-year journey in Beijing, a world vastly different from his rural upbringing. This marked the beginning of his formal ballet education, a journey that started with a reluctant student who would eventually become one of the art form’s most celebrated figures.

Li Cunxin in a dynamic ballet pose.

Li Cunxin in a dynamic ballet pose.

Li Cunxin’s powerful physique and expressive movement, captured in a dance photograph, showcase the dedication and talent that propelled him to international ballet stardom.

From Reluctant Student to Passionate Performer

Despite being selected for the prestigious Beijing Dance Academy, Li’s initial experience with ballet was far from love at first sight. He openly admits to hating ballet in his early years of training. For a young boy whose primary concern was helping his family escape poverty, ballet seemed frivolous and disconnected from his immediate realities. “I saw no connection how I could help my family with ballet. I felt guilty too, because I had food to eat, I wasn’t freezing at winter time like my family was,” Li explains, highlighting the emotional conflict he faced.

His lack of passion translated into a lack of motivation in his training. By his second year, Li was convinced he would be dismissed from the academy, not out of personal disappointment, but out of fear of letting his family down. He perceived himself as a poor dancer, slow to learn and lacking the natural grace expected in ballet. “I was absolutely the laziest, I had no motivation and a lot of the teachers thought I was absolutely stupid and hopeless,” he confesses, revealing the low self-esteem he battled during this period.

The rigorous and often painful training methods of the academy further fueled his aversion to ballet. Extreme stretching and demanding exercises, sometimes leading to injuries, made the experience physically and emotionally challenging. The tedious nature of foundational ballet techniques, with exercises stretched over excruciatingly long counts, added to his boredom and frustration. Performance opportunities, which often ignite a passion for dance in young students, were absent in the initial years, leaving Li feeling disconnected from the potential rewards of his arduous training.

However, a turning point arrived with the introduction of a new ballet teacher, Teacher Xiao. This instructor’s profound passion for ballet proved to be the catalyst that transformed Li’s perspective. Teacher Xiao, who had spent time in Russia and possessed a deep appreciation for the art form, inspired Li in a way no previous teacher had. “His love for the art form had truly inspired me and he was the one who turned me around from that moment onwards,” Li acknowledges, marking this as the pivotal moment of his transformation.

Under Teacher Xiao’s guidance, Li’s perception of ballet shifted dramatically. What was once “the ugliest art form” became “the most beautiful art form.” This newfound passion ignited a fierce dedication and work ethic. Ballet became not just a duty, but a source of “colour, enjoyment, ambition, and aims” in his life. Crucially, Teacher Xiao helped Li connect his ballet aspirations to his deep desire to support his family. Becoming a successful dancer, he realized, could be a means to uplift his family from poverty. This realization, coupled with his growing appreciation for ballet itself, became his driving force, propelling him from a reluctant student to a passionate and dedicated performer.

Defection and Global Stardom with the Houston Ballet

Li Cunxin’s journey took another dramatic turn when he was offered a scholarship to the Houston Ballet, an opportunity that would catapult him onto the international stage but also lead to a significant personal and political crisis. Ben Stevenson, then the artistic director of the Houston Ballet and a former principal dancer with the Royal Ballet, visited China as part of an early cultural exchange. Impressed by Li’s talent during masterclasses at the Beijing Dance Academy, Stevenson offered him and another student scholarships to train in the United States.

This exchange program was initially conceived as a cultural bridge between the USA and China, but Li’s personal decisions would soon test the delicate diplomatic balance. During his time in Houston, Li’s life took a romantic turn when he fell in love with Mary McKendry, an American dancer who had joined the Houston Ballet as a principal dancer. Their connection deepened both on and off stage, and they eventually married. This personal decision had unforeseen international repercussions.

Li’s marriage to an American citizen triggered a major standoff between the United States and China. His subsequent decision to defect to the US while visiting the Chinese consulate in Houston made international headlines. This act of defiance resulted in him being held in the consulate for 21 tense hours, becoming a focal point of international news. The incident transformed Li into a global figure, “Mao’s Last Dancer,” a symbol of artistic freedom and personal choice against political constraints.

Despite the personal turmoil and political storm, Li’s career flourished in the United States. He became a principal dancer with the Houston Ballet, renowned for his exceptional technique, particularly his soaring jumps and dynamic stage presence. His defection, while initially causing immense personal pain due to separation from his family, ultimately paved the way for a remarkable career. The emotional depth and resilience forged through these experiences arguably contributed to the intensity and artistry of his performances, captivating audiences worldwide.

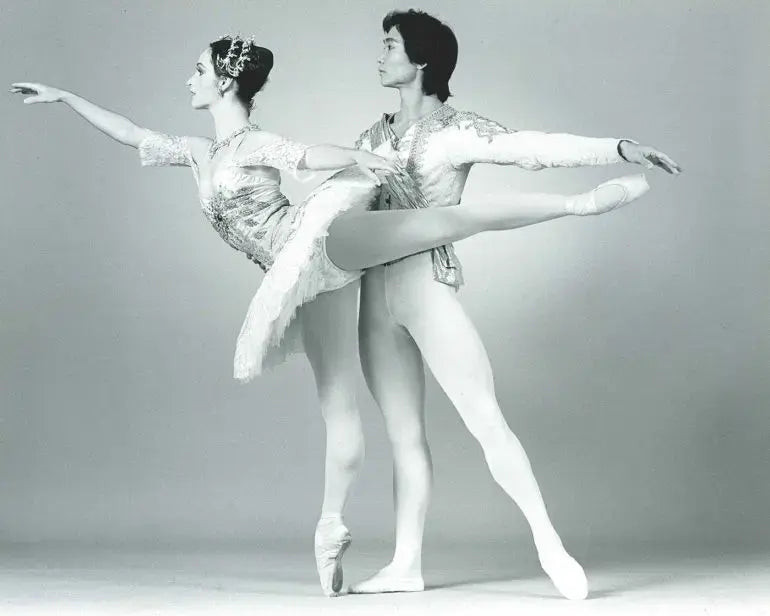

Mary McKendry and Li Cunxin performing together in "Sleeping Beauty".

Mary McKendry and Li Cunxin performing together in "Sleeping Beauty".

A captivating black and white image of Li Cunxin dancing with Mary McKendry in “Sleeping Beauty,” highlighting their artistic partnership and on-stage chemistry during their time with the Houston Ballet.

Nine Years of Separation and a Tearful Reunion

The price of Li Cunxin’s defection was a painful separation from his family in China. For nine long years, communication was severed, and the prospect of reunion seemed distant. This period was, in his words, “the darkest period of my life.” The emotional toll of being cut off from his loved ones was immense, casting a shadow over his burgeoning success in the West. “When I got out of the Chinese Consulate my connection with China was completely cut off with my family. And I couldn’t really write a letter home for quite a few years,” Li recounts, emphasizing the profound isolation he endured.

The pain of separation was compounded by the guilt and longing for his family. Even amidst professional accolades and performances before dignitaries, a deep sense of incompleteness persisted. “Even at times I would eat a piece of meat or fish or receive a prestigious award or be performing in front of presidents and royalty I just wished my parents were there witnessing those beautiful moments in my life,” he shares, revealing the constant ache of their absence. This emotional turmoil even contributed to the breakdown of his first marriage, highlighting the deep personal impact of his political circumstances.

However, fate, once again, had a surprising turn in store. During a performance of “Swan Lake” at the Kennedy Center, attended by Barbara Bush, then the wife of the Vice-President, an unexpected chain of events unfolded. Barbara and George H.W. Bush had been instrumental in Li’s initial visa to the US and were supportive of his career. Learning about Li’s ongoing difficulties in reconnecting with his family during a White House visit, Barbara Bush was surprised and concerned.

Unbeknownst to Li, Barbara Bush intervened on his behalf. She invited the Chinese Ambassador and Cultural Attaché to see him dance, and subsequently, Li was invited to the Chinese embassy. There, he was informed of the Bush’s intervention and a glimmer of hope emerged. Months later, a letter arrived with astonishing news: his parents had been granted permission to visit him in America.

The reunion was orchestrated in secrecy by Ben Stevenson and members of the Houston Ballet. On the opening night of “The Nutcracker,” Li, scheduled to dance the Prince, was unaware of the extraordinary surprise awaiting him. A performance delay, attributed to dignitaries running late, was actually to accommodate his parents’ arrival, who were being escorted through Houston traffic. As his parents were ushered into the theater, the audience erupted in applause, sensing the emotional significance of the moment.

“When my parents were finally led into the theater, the whole audience started to applaud for them,” Li describes the overwhelming scene. The reunion backstage was intensely emotional, marked by tears and profound joy. For Li’s parents, who had never seen him dance and had lived lives of hardship and limited exposure to the world, it was an unforgettable experience. That night’s performance was imbued with a special magic for Li, fueled by the emotional release and the presence of his parents in the audience. After nine years of separation, the family was finally reunited, a moment of profound emotional catharsis that underscored the human dimension of Li’s extraordinary journey.

Mary McKendry and Li Cunxin embracing.

Mary McKendry and Li Cunxin embracing.

A heartwarming photograph of Mary McKendry and Li Cunxin in a close embrace, symbolizing their enduring partnership and the personal bonds that have shaped their lives.

From Dancer to Artistic Director and Family Advocate

After a stellar career as a principal dancer, Li Cunxin transitioned into artistic leadership, becoming the Artistic Director of the Queensland Ballet in Australia. This marked a new chapter in his life, where he could leverage his vast experience and artistic vision to shape the future of a ballet company. His leadership at the Queensland Ballet has been marked by innovation, growth, and a deep commitment to his dancers.

His personal experiences, particularly the isolation he endured during his defection, have profoundly influenced his approach to leadership. Understanding the emotional challenges of separation and isolation, Li prioritized the well-being of his dancers, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. He ensured constant communication, support, and a sense of community within the company, drawing from his own experiences of relying on the support of his ballet family during difficult times. “Throughout the Covid period, particularly during the lockdown period, I reach out to every one of our dancers…made sure that they feel they are still cared for by us and that we are thinking of them and that we want help them, whatever way possible,” Li explains, highlighting his empathetic leadership style.

Beyond his professional achievements, Li’s personal life also took another significant turn with the birth of his daughter, Sophie, who was diagnosed as profoundly deaf. This news initially brought immense grief and shattered the dreams he and his wife, Mary, had envisioned for their daughter. However, this challenge became another testament to their resilience and love. Mary made the selfless decision to step back from her own dance career to dedicate herself to Sophie’s development.

The family’s journey with Sophie has been one of learning, adaptation, and advocacy. Li and Mary, along with their other children, are learning Auslan (Australian Sign Language) to better communicate with Sophie and to embrace her world. This commitment reflects their deep love and respect for Sophie and their dedication to ensuring her full inclusion and participation in life. Sophie’s story, and Mary’s journey as a mother and advocate, are powerfully told in Mary’s autobiography, “Mary’s Last Dance,” which Sophie herself encouraged her mother to write.

Li Cunxin’s life story is a powerful narrative of transformation, resilience, and the enduring human spirit. From the poverty-stricken fields of China to the grand stages of international ballet, and now as a leading artistic director, his journey is an inspiration. “Mao’s Last Dancer” is more than just a title; it encapsulates a life lived with courage, passion, and unwavering dedication to both art and family. His story continues to resonate, reminding us of the power of perseverance, the beauty of art, and the importance of human connection in overcoming life’s challenges.