Before the 13th century, art in Europe often portrayed death with a sense of peace, deeply rooted in Christian beliefs and the promise of eternal life. Serene effigies in cathedrals reflected a strong faith in resurrection and the afterlife. Death was seen as a tranquil transition.

However, the Late Middle Ages brought a dramatic shift in this perception. A period marked by turmoil fostered a complex mix of fear and morbid fascination with death. Artists began to explore darker themes, depicting skeletons and figures engaged in a chilling dance with decaying corpses, sometimes consumed by worms. This era gave birth to a powerful allegory of mortality: the Danse Macabre, also known as the Macabre Dance.

The Shift in Perception: From Serene to Macabre

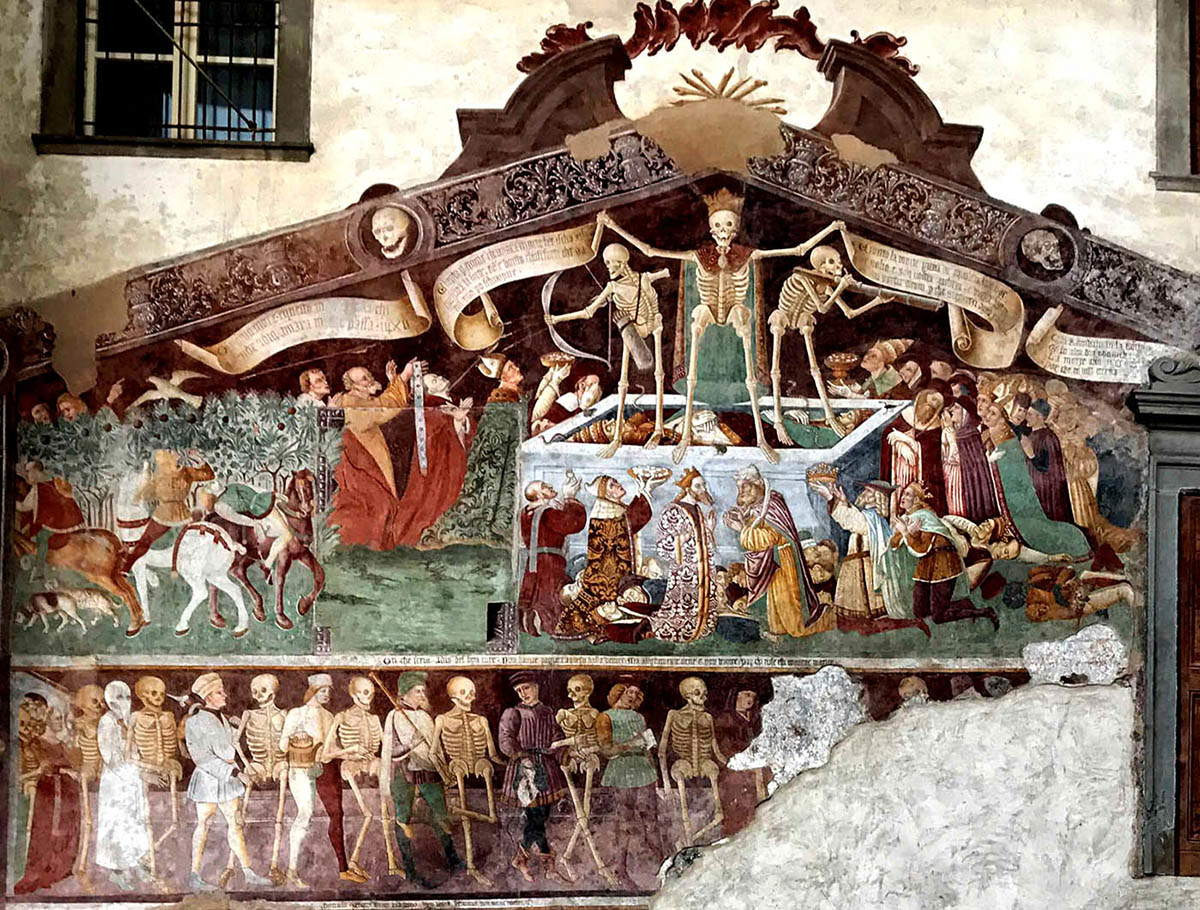

danse macabre triumpth death danse

danse macabre triumpth death danse

Around 1300, Europe stood at a crossroads. The feudal system was flourishing, favorable climates led to abundant harvests, and urban development alongside technological advancements ushered in an era of relative peace. Yet, this prosperity was not to last.

Prosperous conditions fueled rapid population growth. England’s population surged from one million in 1086 to an estimated six or seven million by the 13th century. A similar trend swept across Europe, leading historians to estimate a continental population between 70 and 100 million during the 13th century. This growth strained resources, and by the 14th century, a series of devastating events plunged Europe into crisis.

The Dark Centuries: Famine, Plague, and War

disciplini oratory triumph of death

disciplini oratory triumph of death

Life expectancy in the Middle Ages was already low, averaging between 35 and 40 years in the 13th century, with infectious diseases rampant. However, the calamities of the 14th century were unprecedented, leaving an indelible scar on humanity and amplifying the fear of death.

The Great Famine of 1315-1317 was the first major disaster. In some regions, it stretched until 1322. Repeated crop failures due to adverse weather and livestock diseases led to widespread starvation, disease, increased violence, and death across Europe.

Just a generation later, from 1346 onward, waves of plague decimated the continent. While some forms of bubonic plague were animal-borne, the 14th century witnessed the emergence of a terrifying airborne strain that spread with alarming speed. The Black Death, as it became known, wiped out between 30% and 50% of Europe’s population – approximately 25 million lives – within just five to six years. Some areas suffered even more drastically. Germany lost an estimated 40% of its population, Provence in southeastern France mourned half its people, and Tuscany, Italy, experienced a staggering 70% mortality rate.

michael wolgemut nuremberg chronicle

michael wolgemut nuremberg chronicle

Adding to this devastation, the protracted conflicts of the Hundred Years’ War further weakened Europe. For over a century, from 1337 to 1453, France and England were locked in a struggle for dynastic control of France.

The combination of overpopulation, worsening climate conditions in the 14th and 15th centuries, and these monumental disasters triggered a societal transformation. Scarce resources intensified competition, widening the gap between landowners and peasants, the rich and the poor.

These tumultuous times profoundly impacted how people viewed death. Death became an ever-present possibility, indiscriminately striking down the old and young, men and women in their prime. The sheer volume of corpses, often left unburied in streets due to overwhelming numbers, must have deeply traumatized the populace. This pervasive gloom permeated the art of the Late Middle Ages.

Memento Mori: Remember You Must Die

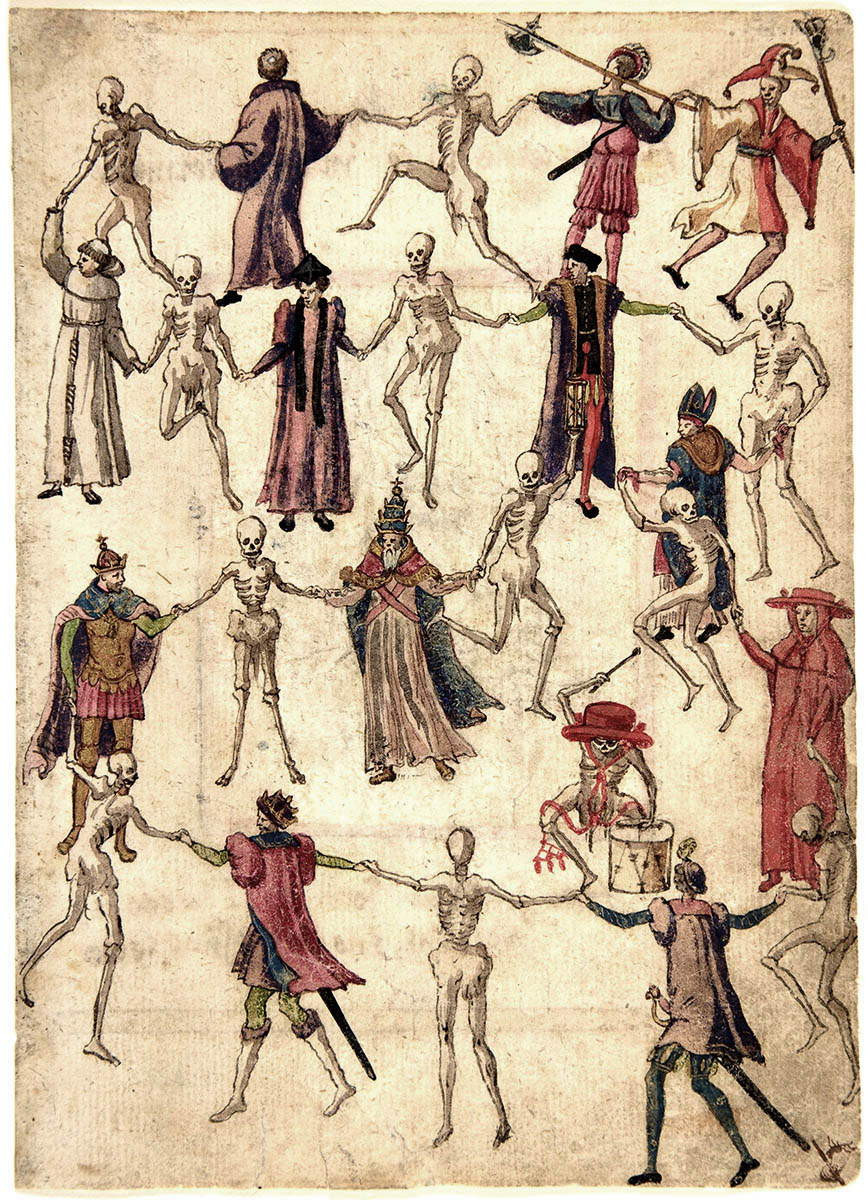

the dance of death drawing

the dance of death drawing

Amidst this climate of fear, artists sought new ways to represent death. The concept of Memento Mori, Latin for “remember you must die,” gained widespread traction in medieval arts and architecture. It later evolved into Vanitas, a prominent genre in 16th and 17th-century Dutch painting. Memento Mori also connected to two influential medieval Latin texts known as the Ars Moriendi, or “The Art of Dying,” published around 1415 and 1450. These texts provided guidance on achieving a “good” death within the framework of Late Middle Age Christian beliefs.

Like other medieval illustrations, Memento Mori imagery served as an educational tool for a largely illiterate population. People needed constant reminders of life’s fleeting nature and the inevitability of death. Memento Mori became a recurring motif in late medieval art.

lucerne dance of death painting

lucerne dance of death painting

While 13th-century effigies often display serene faces and fine attire, projecting an image of peace, from the latter half of the 14th century onwards, sculpted tombs took a starkly realistic turn. Cadaver tombs emerged, depicting the deceased in a state of decay, revealing rotting flesh or skeletons often shrouded in decaying cloth.

Danse Macabre: The Dance of Death Emerges

The “Transi Tomb of Guillaume de Harcigny,” an anonymous work from 1394, illustrates the cadaver tomb trend.

Many sculptors embraced a morbid trend already present in medieval literature, drama, and graphic arts: the Danse Macabre. The French term “macabre” itself appeared in the 1376 poem Respit de la Mort by Jean le Fèvre. The Danse Macabre, or Macchabaeorum Chorea in Latin, stands as the epitome of horrifying death depictions in late medieval art, characterized by decaying bodies and skeletons.

Originating in late 13th-century literature, the Danse Macabre is an allegory of Death, portraying a dance uniting the living and the dead, rich and poor alike. Figures are depicted according to their social standing, from the Pope to commoners and children. The Danse Macabre functions as social satire, exposing human vanities and vices, and rapidly gained notoriety across Europe, especially among the common populace. It visually communicated the powerful message that death equalizes everyone, regardless of social status.

danse macabre saint germain church painting

danse macabre saint germain church painting

The personification of Death often leads the procession in the Danse Macabre. This theme found expression in diverse artistic forms: literature, painting, music, and even choreography. Before its depiction on walls, the Danse Macabre was likely performed in churches or sacred spaces.

Graphic representations often feature musical instruments and figure positioning that suggest a circular dance. However, this is no joyful celebration; the living are compelled to dance with ghastly figures. Dance, in this context, becomes a form of punishment. Christianity often viewed dance with suspicion, associating it with pagan rituals and potential vice. Yet, during the Middle Ages, dance and religion coexisted, with dancing occurring within churches or cemeteries during Christmas or Easter.

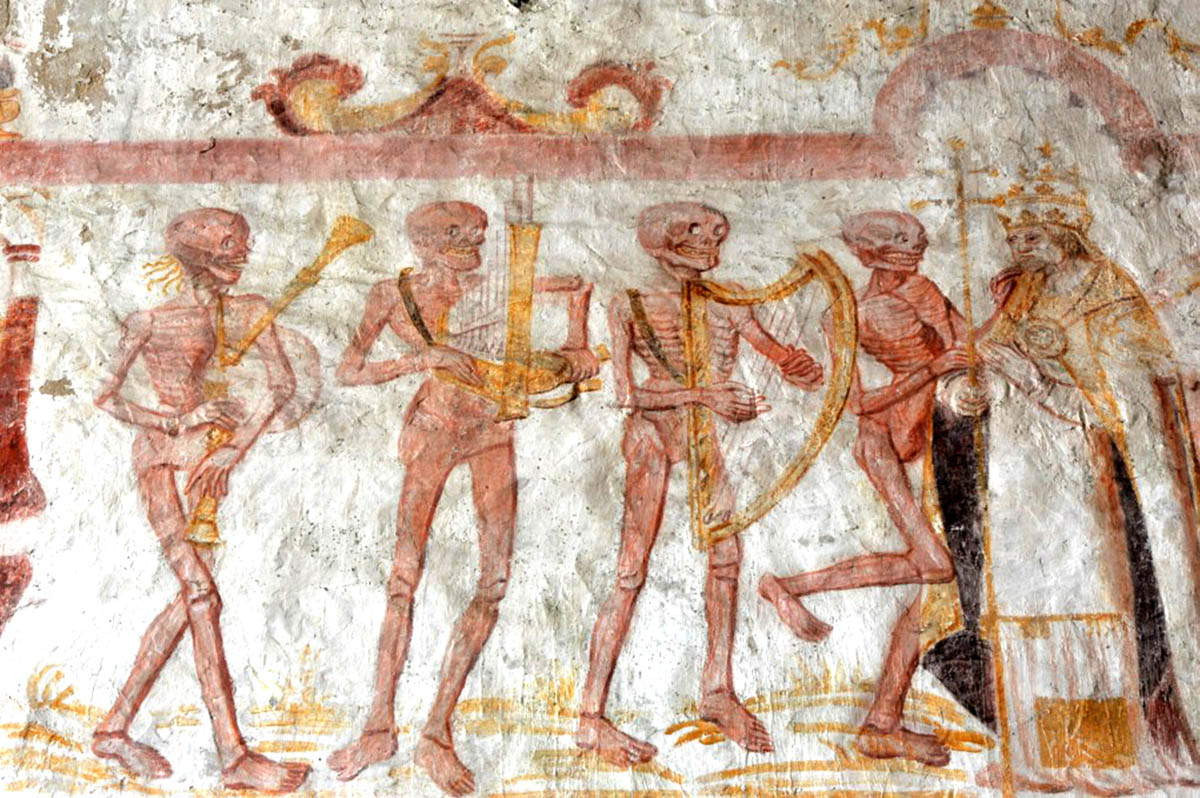

danse macabre skeletons musicians

danse macabre skeletons musicians

Another peculiar phenomenon of the late Middle Ages, possibly related to the Danse Macabre, is the infamous “dancing plague.” Across Europe, hundreds of individuals were afflicted by a strange condition that compelled them to dance frantically in groups for days without rest. Often, they would gather in churches or cemeteries, believing themselves cursed. These events presented a truly disturbing spectacle. Whether caused by epileptic fits or mass hallucination remains unclear; the origin of the dancing plague is still debated.

The Dancing Plague of 1518 in Strasbourg, France, prompted city authorities to organize the dancing mania in designated locations around the city. They even hired musicians to encourage dancing until exhaustion. The link between dance and death was, once again, palpable.

The Holy Innocents’ Cemetery: Ground Zero for the Macabre Dance

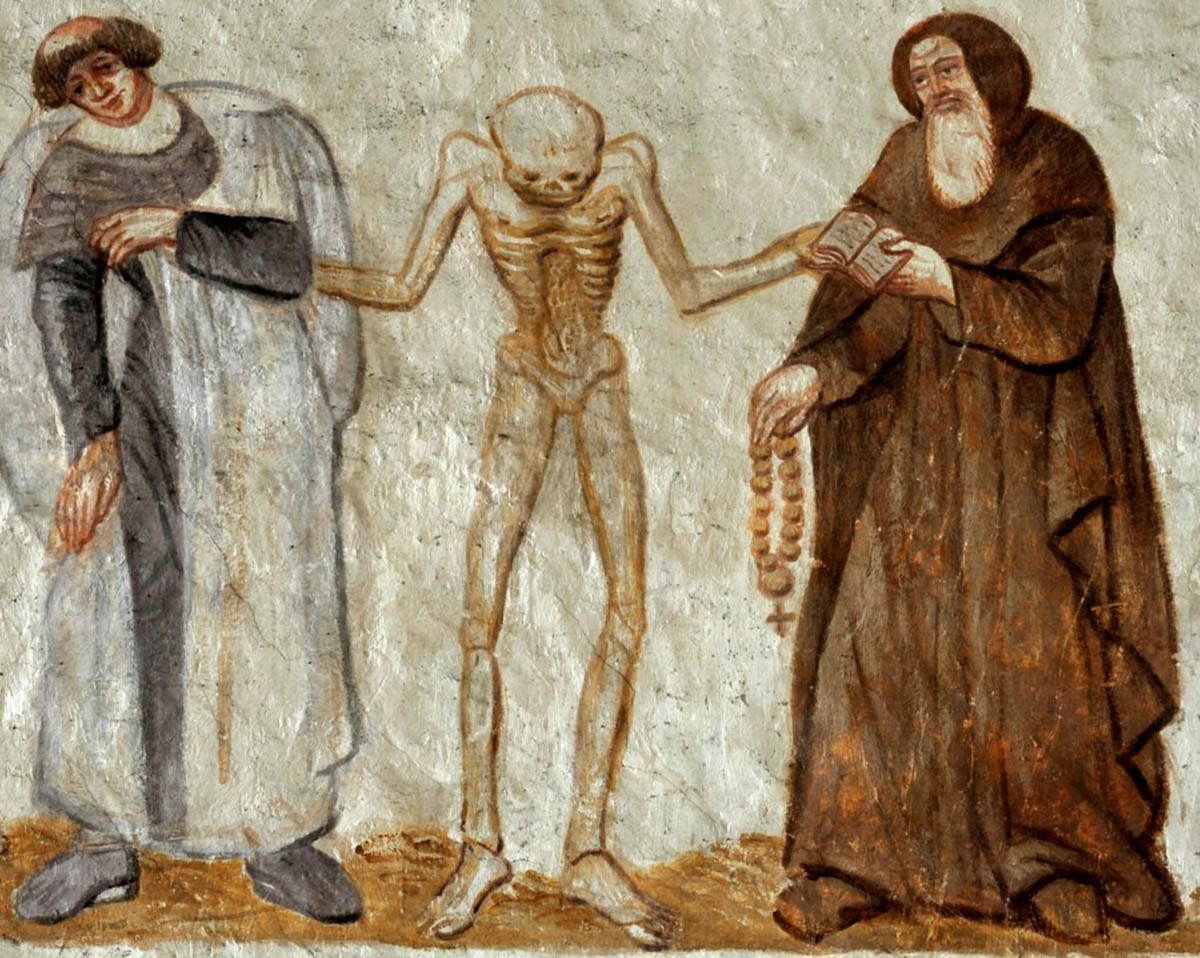

danse macabre skeleton saint germain

danse macabre skeleton saint germain

According to a Parisian bourgeois journal, a Danse Macabre was painted in 1424 in the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery in Paris, marking the earliest known pictorial representation of the theme in Europe. The Holy Innocents’ Cemetery held significant importance at the heart of medieval Parisian life. Over centuries, it became the final resting place for over 10 million bodies, often interred in mass graves. Contrary to modern perceptions of cemeteries as quiet places, it was a vibrant hub of medieval life. People traversed it, socialized, purchased food and goods from vendors, and enjoyed theatrical performances within its grounds. Despite its sacred status, the cemetery functioned as a center for daily life.

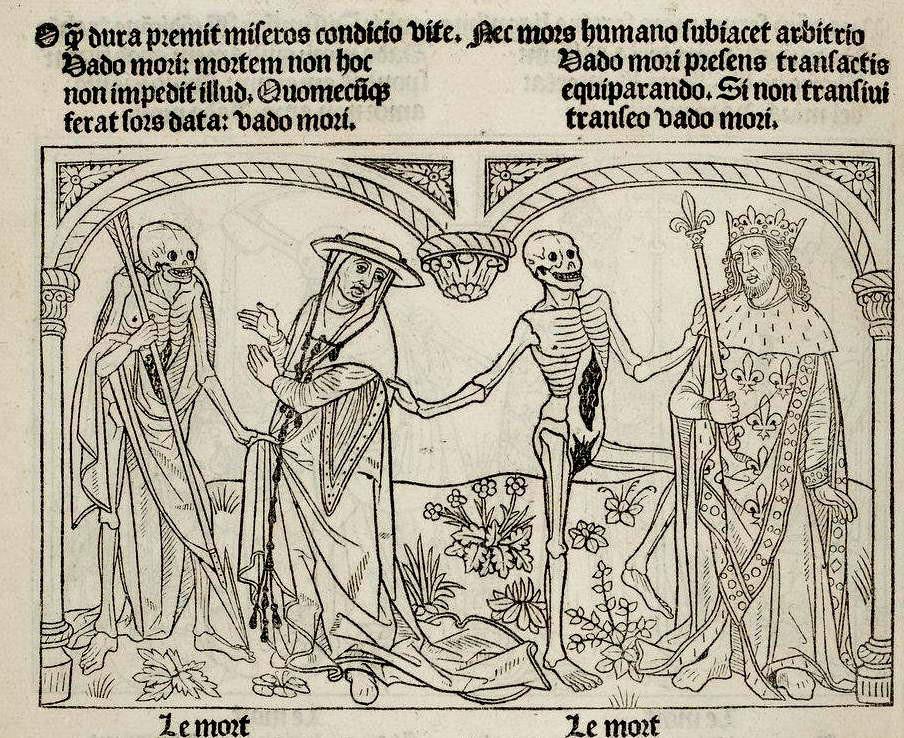

guyot danse macabre cardinal and king

guyot danse macabre cardinal and king

Jehan of Orléans, painter to King Charles VI of France and his brother Louis I, Duke of Orléans, is believed to have painted the scene on an arcade wall bordering one of the cemetery’s mass graves. Jehan depicted figures of royal and religious authority dancing with skeletons and corpses.

The Danse Macabre of the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery in Paris was destroyed in 1669 to make way for urban development. However, its macabre imagery gained widespread circulation thanks to Parisian printmaker Guyot Marchant, who reproduced the cemetery’s paintings. The Holy Innocents’ Danse Macabre likely served as the original model that inspired countless subsequent representations across Europe, initiating the macabre trend.

The Enduring Legacy of the Danse Macabre

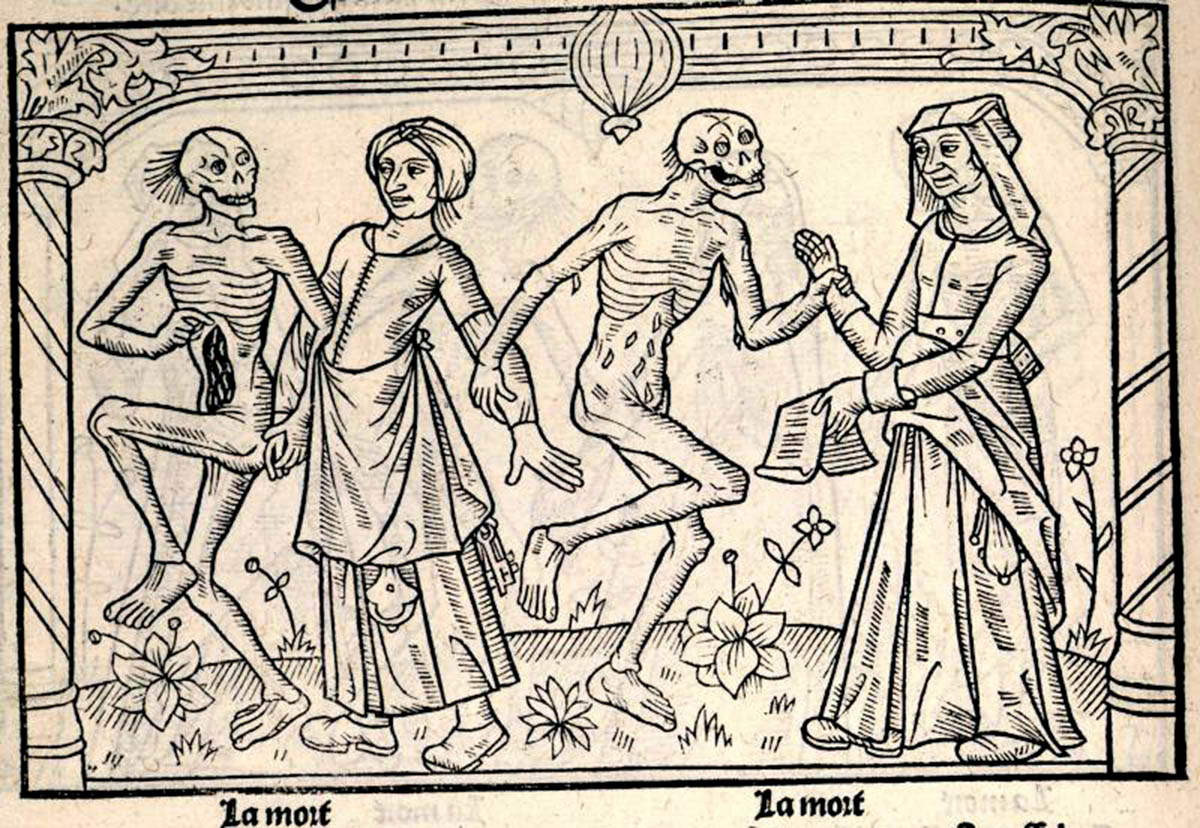

guyot danse macabre chambermaid and housekeeper

guyot danse macabre chambermaid and housekeeper

Numerous Danse Macabre scenes can be found adorning church and cloister walls, particularly in France and Northern Europe. Germany, England, Switzerland, Estonia, and Finland boast some of the finest examples of Danse Macabre artworks.

Prints became the preferred medium for disseminating Danse Macabre themes, offering an efficient way to spread ideas among the populace. Tragically, most of these fragile prints have been lost to time, as have many Danse Macabre paintings on church and cemetery walls. Yet, the theme’s immense popularity led to its adoption on various religious and secular objects, including church curtains and metalwork, jewelry, furniture, and architectural elements within private homes. The Danse Macabre transcended a mere artistic trend; it deeply permeated people’s lives in the aftermath of the Late Middle Ages.

Hans Holbein the Younger’s “Dance of Death (Gentleman, New-married Lady, Pedlar),” circa 1526, part of his woodcut series.

The theme continued to captivate audiences during the 15th and 16th centuries. In 1526, Hans Holbein the Younger created his influential Dance of Death woodcut series. Inspired by the Danse Macabre at the Dominican monastery cemetery in Basel, Switzerland, Holbein depicted Death startling individuals engaged in everyday activities.

hugo simberg dancing with death

hugo simberg dancing with death

Later, artists moved the theme beyond its solely religious context, using it to critique contemporary ideas and offer commentary on political events. The Danse Macabre resonated strongly with artists of the Romantic movement. Though firmly rooted in the anxieties of the Late Middle Ages, the Danse Macabre has become a recurring and powerful theme throughout art history. The troubled era of the late Middle Ages indelibly shaped how death was perceived and artistically represented, leaving a legacy of macabre dance imagery that continues to fascinate.