Kabuki, a mesmerizing form of traditional Japanese theatre, is renowned for its highly stylized dance, drama, and song. A vibrant tapestry woven with music, elaborate dance movements, mime artistry, and breathtaking stagecraft and costumes, Kabuki has captivated audiences in Japan and worldwide for four centuries. Emerging as a major theatrical art form, Kabuki’s very name, suggesting “unorthodox” and “shocking,” hints at its revolutionary beginnings. In contemporary Japanese script, Kabuki is elegantly represented by three characters symbolizing “song” (ka), “dance” (bu), and “skill” (ki).

Kabuki plays, celebrated for their lyrical narratives, are often viewed less as literary masterpieces and more as showcases for actors to exhibit their vast repertoire of performance skills, both visual and vocal. These dedicated performers, often inheriting their roles and artistic lineages, meticulously preserve Kabuki traditions, passing them down through generations with only subtle refinements. Many Kabuki actor families proudly trace their ancestry and performance styles back to the earliest pioneers of Kabuki, denoting their lineage by adding a “generation number” to their stage names.

The Historical Genesis of Kabuki Dance

Kabuki’s origins can be traced back to the early 17th century, with a captivating female dancer named Okuni, formerly an attendant at the Grand Shrine of Izumo. Okuni gained widespread acclaim for her performances that cleverly parodied Buddhist prayers. Gathering a troupe of itinerant female artists, she and her company presented dances and theatrical acts that quickly gained popularity. Okuni’s Kabuki marked a significant turning point as the first major dramatic entertainment intentionally crafted to appeal to the tastes of the common populace in Japan.

However, the overtly sensual nature of these early Kabuki Dances, coupled with the actors’ involvement in prostitution, was deemed too disruptive by the ruling government. In 1629, a pivotal ban was enacted, prohibiting women from performing Kabuki. Subsequently, young boys, dressed as women, took over these roles. Yet, this iteration of Kabuki was also suppressed in 1652 due to persistent concerns about public morality. Ultimately, older men stepped into the female roles, giving rise to the all-male Kabuki tradition that has remarkably endured to this day. As Kabuki evolved, the plays became more sophisticated, and the art of acting achieved new levels of subtlety and depth.

By the dawn of the 18th century, Kabuki had firmly established itself as a respected and mature art form, capable of delivering profound dramatic narratives and genuinely moving portrayals of human experiences. As merchants and commoners gained social and economic prominence in Japan, Kabuki, as the quintessential people’s theatre, became a potent voice reflecting contemporary society. Historical events were frequently adapted for the Kabuki stage. A prime example is Chūshingura (1748), a play that faithfully dramatized the famous 1701–03 incident of the 47 rōnin (masterless samurai) who patiently waited for nearly two years to avenge the forced suicide of their lord. Similarly, many “lovers’ double suicide” (shinjū) plays penned by the renowned playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon drew inspiration from actual tragic pacts between ill-fated lovers.

In contrast to Bugaku, the stately dance ceremony of the imperial court, and Noh theatre, both ancient art forms reserved for the nobility and samurai warrior class, Kabuki became the beloved theatre of the townspeople and farmers. While Bugaku and Noh are characterized by delicate refinement and subtle movements, Kabuki embraced a more robust and unrestrained style, its beauty often described as flamboyant and extravagant.

Kabuki shares significant connections with Noh and jōruri, the Japanese puppet theatre that flourished in the 17th century. Kabuki adopted considerable material from Noh, and following its ban in 1652, Kabuki reinvented itself by adapting and parodying kyōgen, the comic interludes in Noh performances. This period also witnessed the rise of onnagata, specialist actors who portrayed female roles with remarkable skill and artistry, often becoming the most celebrated performers of their time.

The Dynamic Kabuki Audience Experience

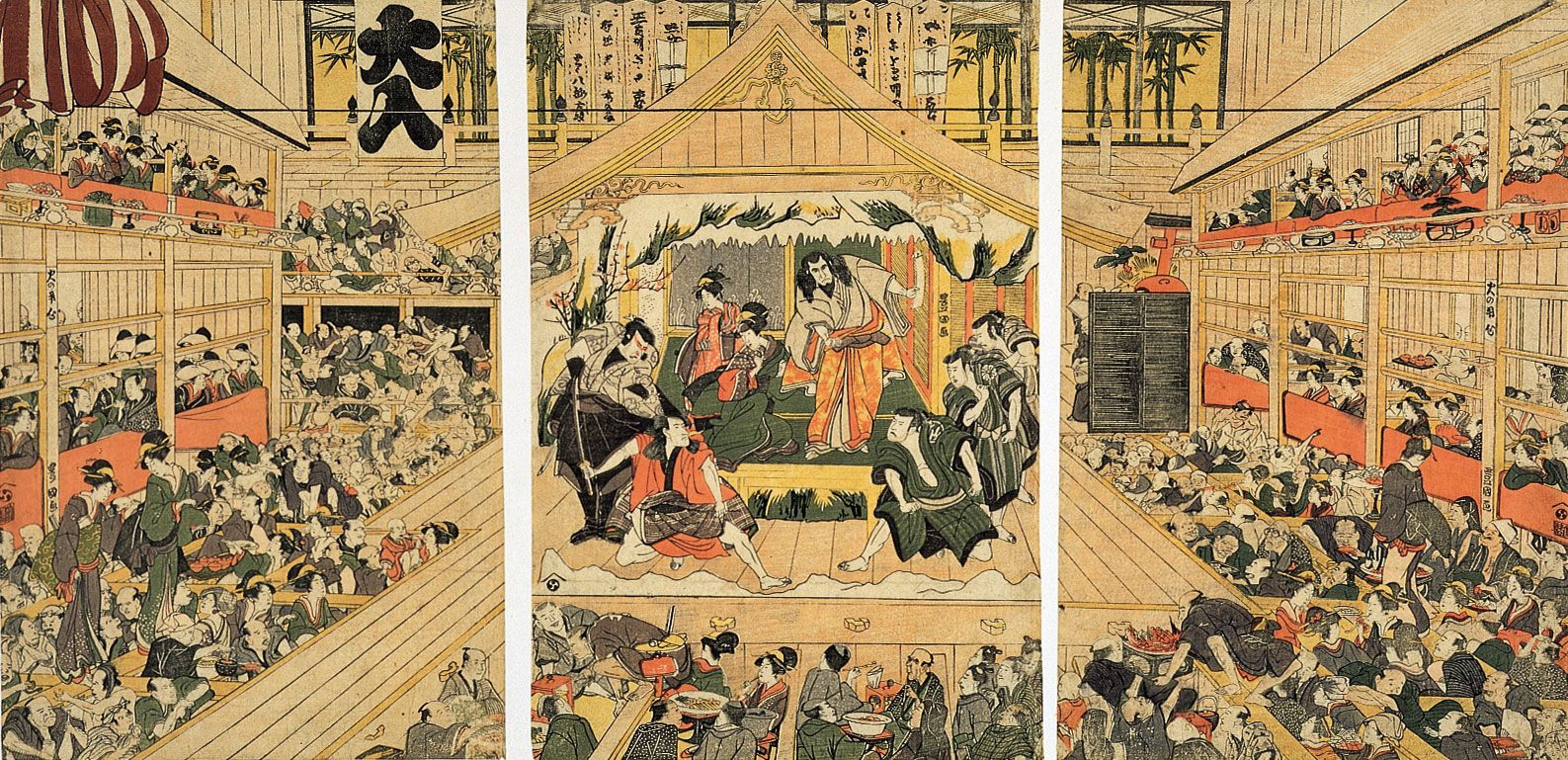

Traditionally, Kabuki performances fostered a lively interaction between actors and spectators. Actors would frequently break the fourth wall, directly addressing the audience, who, in turn, responded with enthusiastic praise or rhythmic clapping according to established conventions. Spectators also commonly called out the names of their favorite actors during performances, creating an atmosphere of shared excitement.

Kabuki programs were known for their extended duration, often spanning from morning until evening. Many audience members would attend for only select plays or scenes, resulting in a constant flow of people entering and leaving the theatre. Meals were served within the theatre, further contributing to a relaxed and communal atmosphere. Kabuki programs often incorporated seasonal themes and contemporary events, ensuring relevance and topicality. Unlike many Western theatres that, since the late 17th century, have employed a proscenium arch to separate performers from the audience, Kabuki intentionally blurred this boundary. The use of hanamichi, elevated passageways extending from the main stage into the auditorium, effectively placed the audience amidst the performance, surrounded by three stages.

Kabuki Themes, Purpose, and Conventions

Kabuki repertoire is broadly categorized into historical plays (jidaimono) and domestic plays (sewamono). A typical Kabuki program presents these in sequence, often interspersed with dance plays featuring supernatural beings, courtesans, and other fantastical characters. The program usually culminates in a vibrant dance finale (ōgiri shosagoto) involving a large ensemble cast.

While Kabuki’s primary aim is entertainment and showcasing the actors’ artistry, it also incorporates a didactic dimension, reflecting the ideal of kanzen-chōaku (“reward the virtuous and punish the wicked”). Kabuki plays frequently explore conflicts rooted in religious concepts such as the impermanence of the world (Buddhism) and the importance of duty (Confucianism), as well as broader moral sentiments. Tragedy often arises when societal morality clashes with intense human passions. Structurally, Kabuki plays typically weave together multiple storylines (suji) but may lack the singular unifying element characteristic of Western drama. Instead, they present a rich tapestry of interwoven episodes progressing toward a dramatic climax.

Despite its adaptability to incorporate new elements, Kabuki remains a highly formalized theatrical tradition. It preserves numerous conventions inherited from earlier forms of theatre performed in shrines and temples. Kabuki dance is arguably its most iconic feature. Opportunities for dance are seamlessly integrated throughout performances, ranging from the graceful, flowing movements of onnagata to the exaggerated, dynamic postures of male characters. Indeed, Kabuki acting is so stylized that it often blurs the lines between acting and dance.

Today, regular Kabuki performances are held at the National Theatre in Tokyo, which actively strives to uphold historical traditions and preserve Kabuki as a classical art form. While the historic Kabuki-za Theatre in Tokyo closed in 2010, a modern office tower incorporating a state-of-the-art theatre opened on the same site in 2013, ensuring Kabuki’s continued presence in the city. Other theatres also host occasional Kabuki performances, and various Kabuki troupes tour and perform outside Tokyo, ensuring the art form’s accessibility and reach. At the National Theatre, a typical Kabuki program lasts approximately four hours, offering audiences a comprehensive immersion into this captivating theatrical world.