The Ghost Dance Movement, a spiritual awakening that swept through Western American Indian communities in the late 19th century, remains a significant chapter in Native American history. Rooted in visions of renewal and peace, it tragically culminated in the Wounded Knee Massacre, forever linking hope and despair in its narrative.

The seeds of the Ghost Dance were sown in the late 1860s with Paiute elder Wodziwob. Around 1869, Wodziwob experienced visions promising a revitalized Earth and relief for the Paiute people, who were suffering from the devastating effects of European diseases. Following a severe typhoid epidemic in 1867, these visions offered solace and hope. Initially, Wodziwob’s prophecies spoke of a cataclysm that would remove European settlers, leaving only Native Americans. His visions evolved, later foreseeing an event that would remove all people, after which faithful practitioners of ancestral spirituality would be miraculously restored to a renewed world. Ultimately, his message shifted towards a peaceful, immortal existence for those who adhered to his spiritual teachings, marking the early stages of the Ghost Dance spiritual movement. A central element of this early movement was a communal circle dance ceremony. Wodziwob’s influence waned after his death in 1872, but the underlying yearning for spiritual renewal persisted.

The movement gained renewed momentum in 1889 with Wovoka, a Northern Paiute also known as Jack Wilson. On January 1, 1889, during a solar eclipse, Wovoka experienced a profound dream. His prophecy echoed Wodziwob’s, envisioning the disappearance of European settlers, the return of buffalo herds, and the restoration of Native American lands across the continent. Ancestors would return to life, and a time of peace would dawn. Having been raised by a European American family, Wovoka’s teachings emphasized peaceful coexistence with white Americans. Influenced by Christianity, his prophecies sometimes mentioned Jesus or a messianic figure. Wovoka proclaimed that practicing the circle dance ceremony would bring about this vision of a peaceful world.

News of Wovoka’s prophecies spread rapidly. Representatives from diverse tribes journeyed to meet him, and letters explaining his vision and the Ghost Dance ceremony circulated among Native American communities. Leaders of the movement traveled extensively, teaching others about the prophecy and the dance, contributing to the rapid dissemination of the Ghost Dance movement across the American West.

A group of dancers in Native American dress form a circle around an American Flag.

A group of dancers in Native American dress form a circle around an American Flag.

Dance held a significant place in many Native American spiritual traditions, and the Ghost Dance ceremony built upon the familiar round dance. This communal dance, common among various tribes for social gatherings and healing rituals, involved participants holding hands and moving in a circle with a shuffling step, swaying to the rhythm of songs. While traditional round dances often featured a central drum, the Ghost Dance typically omitted the drum, sometimes featuring a pole or tree at the circle’s center, or sometimes nothing at all. The specifics of the dance varied among different groups who adopted it, reflecting the diverse cultural adaptations of the Ghost Dance movement.

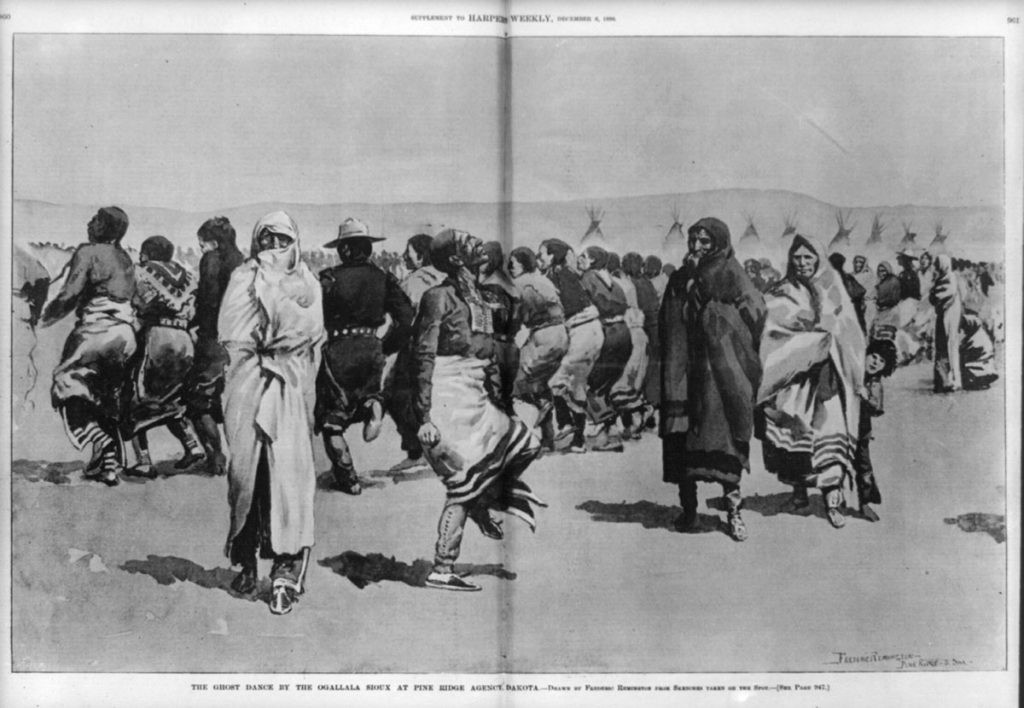

According to James Mooney, an ethnographer who extensively studied the Ghost Dance, the dance could induce a trance-like state in participants. Some dancers actively sought this trance, sometimes aided by someone waving a feather or cloth to focus their gaze. Songs with faster rhythms were used to facilitate trance and visions. Those entering a trance might leave the dance circle to dance individually or lie on the ground, experiencing the spiritual intensity of the Ghost Dance. Frederic Remington’s depiction of the Ghost Dance, featured at the beginning of this article, visually represents this phenomenon, showing dancers in the background and figures in the foreground who appear to have entered a trance state, mirroring Mooney’s descriptions.

Ghost Dance songs followed a distinctive pattern: a line repeated twice, followed by another line repeated twice, and so on. Judith Gray, an expert in American Indian music at the American Folklife Center, noted that this pattern was common among Paiute and other Northwest Plateau peoples but not among Plains Indians or many other groups who embraced the Ghost Dance. Despite its novelty to many, this song structure became integral to Ghost Dance music, adapted and sung in various Native American languages, demonstrating the movement’s ability to integrate and transform existing cultural forms.

The rapid spread of the Ghost Dance movement and the intertribal communication it fostered caused alarm among European Americans, becoming a concern for the U.S. Army. While many white Americans perceived the Ghost Dance as a war-like and militant movement, it was fundamentally a peaceful form of resistance rooted in Native American spirituality. It arose from desperation, a response to broken treaties and forced confinement on reservations. For Plains Indians, the era was marked by starvation following the mass slaughter of buffalo, their primary food source and way of life. From a Native American perspective, European actions were not only destroying their cultures but also the very environment, rendering the plains uninhabitable. European American fear and misunderstanding clashed with the spiritual and survival-driven motivations behind the Ghost Dance.

James Mooney recognized the mischaracterization of the Ghost Dance in popular media and dedicated himself to correcting these inaccuracies. His research, initially published in 1890 and later expanded into a book in 1896, aimed to dispel prejudiced and inaccurate newspaper accounts. While the press fueled fears of a dangerous Indian uprising connected to the dance, Mooney emphatically asserted its peaceful nature. He conducted extensive fieldwork between 1890 and 1894, traveling approximately 32,000 miles and spending time with around twenty tribes. As a participant observer, Mooney engaged in Ghost Dance ceremonies with the Arapaho and Cheyenne, documented testimonies, and took photographs. Ethnographers of the time were captivated by the Ghost Dance as a rare instance of a new religion rapidly emerging, transcending cultural and linguistic boundaries, making Mooney’s work particularly significant.

Mooney traced the Ghost Dance beliefs to earlier prophecies within various Native American groups predicting land restoration and a return to pre-European life. These prophecies emerged soon after European colonization and the ensuing conflicts. Thus, while the Ghost Dance appeared to be a sudden phenomenon, its core ideas had deep historical roots in Native American responses to colonization and cultural disruption.

An elderly man lies in the snow.

An elderly man lies in the snow.

Tragically, the Ghost Dance movement became intertwined with one of the darkest episodes in American history: the Wounded Knee Massacre. On December 15, 1890, tensions surrounding Ghost Dance ceremonies led to the killing of Chief Sitting Bull by police at Standing Rock Reservation. Subsequently, a group of over 300 Miniconjou Lakota, led by Chief Spotted Elk (Big Foot), sought refuge at Pine Ridge Reservation. They were intercepted by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee Creek and forcibly detained. As soldiers disarmed the Lakota men, gunfire erupted. Accounts of what triggered the shooting vary, but the result was devastating. Estimates suggest that between 150 and 300 Lakota people, many unarmed women and children, were killed, including those who perished from exposure and wounds afterward. Spotted Elk, unarmed and ill with pneumonia, was among the slain. The Army suffered 25 casualties.

Mooney meticulously documented the events leading up to, during, and after the Wounded Knee Massacre. He included firsthand accounts and testimonies from those who visited the site shortly after. Mooney estimated the total death toll at around 300, accounting for those who died immediately, later from wounds, or from exposure. Despite the horrific nature of the event, it was initially portrayed as a battle, the soldiers were hailed as heroes, and some received the Congressional Medal of Honor. However, perspectives shifted significantly with time. Dee Brown’s 1971 book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, and the rise of the Indian civil rights movement brought forth the Native American perspective, leading to a re-evaluation of history. Today, the event is widely recognized as the Wounded Knee Massacre, a stark reminder of the tragic consequences of fear and misunderstanding.

In the aftermath of Wounded Knee, the Ghost Dance was misrepresented as a failed and dangerous movement. The Bureau of Indian Affairs attempted to suppress it, reinforcing the idea that it had ended in 1890. However, the Ghost Dance ceremony persisted into the early 20th century, and its songs remain part of Native American traditions today. James Mooney’s recordings and research serve as vital resources for understanding the true nature of the Ghost Dance beyond the sensationalized accounts of his time. The legacy of the Ghost Dance, including its message of peaceful resistance, continues to resonate within Native American activism and spirituality. Even today, the spirit of peaceful resistance and hope for a better future, inherent in the Ghost Dance movement, can be seen in ongoing efforts for Indian rights and cultural preservation.