The Ghost Dance was a significant religious movement that emerged among Western American Indian tribes in the late 19th century. Rooted in visions of renewal and peace, it promised a world free from suffering and the return of traditional ways of life. While intended as a peaceful spiritual practice, it was tragically misunderstood and contributed to one of the darkest events in American history, the Wounded Knee Massacre.

James Mooney, a prominent ethnographer, documented the Ghost Dance extensively in the 1890s. His recordings of Ghost Dance songs, recently updated as part of the Emile Berliner and the Birth of the Recording Industry collection at the Library of Congress, offer invaluable insight into this movement. These recordings, like the Caddo Ghost Dance Song no. 2, capture the essence of the Ghost Dance ceremonies. It’s important to note that in the early days of ethnography, researchers like Mooney often learned and performed these songs themselves to ensure accurate preservation before recording technology was widespread.

{mediaObjectId:'517518FC117F012AE0538C93F116012A',metadata:["James Moody. 'Caddo Ghost Dance Song no. 2'"],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

Origins and Prophecies of Renewal

The Ghost Dance first arose among the Paiute people around 1869, inspired by the visions of an elder named Wodziwob. These visions offered hope in a time of immense hardship for Native Americans, who were suffering greatly from disease and displacement due to European colonization. Wodziwob’s prophecies spoke of a coming renewal of the Earth, a cataclysm that would remove the European settlers and restore the world to its original state, inhabited solely by Native peoples and their ancestors.

Initially, Wodziwob’s visions predicted the disappearance of Europeans. Later, his prophecies evolved to describe an event that would remove all people, followed by a miraculous return only for those who faithfully practiced traditional spirituality. Eventually, his message shifted to focus on a peaceful, immortal life for those who adhered to his spiritual teachings, regardless of the fate of the Europeans. Central to this spiritual practice was a communal circle dance. Wodziwob passed away in 1872, but his early visions laid the groundwork for the later, more influential Ghost Dance movement.

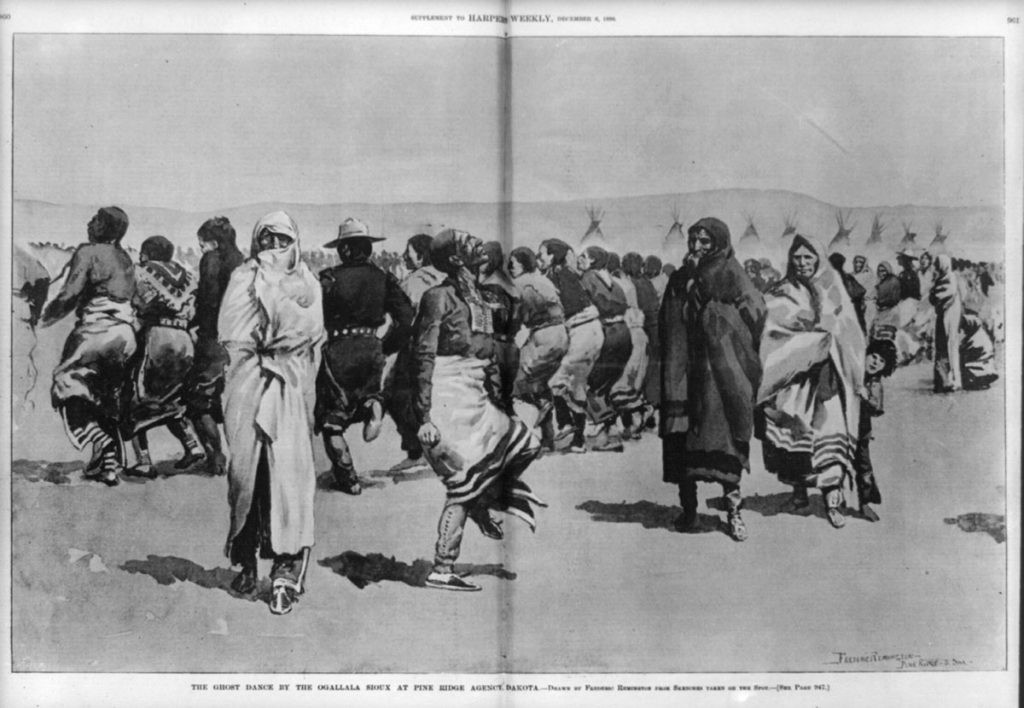

The Ghost Dance among the Oglala Lakota as depicted by Frederic Remington, 1890. Alt text: 1890 illustration of the Ghost Dance, showing a circle of Native American dancers in the background and foreground figures observing the ceremony.

Wovoka and the 1890 Prophecy

The Ghost Dance movement gained significant momentum with the emergence of Wovoka, a Northern Paiute man also known as Jack Wilson. On January 1, 1889, during a solar eclipse, Wovoka experienced a profound dream. His prophecy echoed Wodziwob’s but became more widely influential. Wovoka proclaimed that the European settlers would depart or vanish, the buffalo herds would return, and the ancestral lands would be restored to Native American tribes across the continent. In his vision, deceased ancestors would be resurrected, and all would live in peace and harmony.

Wovoka’s upbringing contributed to the unique character of his teachings. Raised by the European American family of David Wilson after his father’s death, he was exposed to Christianity. Consequently, his prophecies incorporated elements reminiscent of Christian messianic beliefs, sometimes mentioning Jesus or a messiah figure. However, the core of his message remained rooted in Native American spirituality. He taught that performing the circle dance ceremony would hasten the arrival of this peaceful new world. Crucially, Wovoka emphasized maintaining peaceful relations with white Americans, advocating for a path of non-violence and spiritual practice to achieve the prophesied renewal.

Spread and Practice of the Ghost Dance

News of Wovoka’s prophecy spread rapidly. Representatives from numerous tribes journeyed to meet him and learn about the Ghost Dance. Letters explaining the vision and the associated ceremony were disseminated among various Native American communities. Leaders of the movement traveled to different nations, teaching the Ghost Dance and its songs.

The Ghost Dance ceremony itself was based on the traditional round dance, a common practice among many Native American groups for social gatherings and healing rituals. Participants would join hands and dance in a circle, moving with a shuffling side-to-side step, swaying to the rhythm of songs. While traditional round dances often featured a drum at the center, the Ghost Dance typically omitted the drum. Instead, a pole or tree might stand in the center, or sometimes nothing at all. The specific details of the dance varied slightly among different tribes who adopted it, reflecting local customs and interpretations.

According to James Mooney’s observations, the Ghost Dance could induce a hypnotic state in some participants. Some dancers actively sought to achieve a trance, sometimes aided by someone waving a feather or cloth to focus their gaze. Faster-paced songs were used to facilitate trance and visions. Those experiencing a trance might leave the dance circle to dance individually or lie on the ground, as depicted in Frederic Remington’s illustration.

Ghost Dance songs followed a distinctive pattern: a line repeated twice, followed by another line repeated twice, and so on. Judith Gray, an expert at the American Folklife Center, notes this pattern was common among Paiute and Northwest Plateau peoples but not among Plains Indians or many other tribes who embraced the Ghost Dance. Despite this unfamiliar structure, various tribes adopted and adapted the song form, creating Ghost Dance songs in their own languages.

{mediaObjectId:'517518D47350014AE0538C93F116014A',metadata:["James Moody. 'Arapaho Ghost Dance Songs no. 44 and 45'"],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

This recording features two Arapaho Ghost Dance Songs, showcasing the variations in tempo and style. The first song demonstrates a slower rhythm compared to the second.

Misunderstanding and Fear

The rapid spread of the Ghost Dance across diverse Native American communities in the Western United States caused alarm among European Americans. The movement was misinterpreted as a sign of impending Indian uprising, becoming a significant concern for the U.S. Army.

Contrary to popular perception, the Ghost Dance was not a militant movement. Instead, it represented a peaceful, albeit desperate, form of resistance rooted in Native American spiritual beliefs. It emerged from the dire circumstances faced by Native Americans, who were subjected to broken treaties, forced onto reservations, and faced starvation due to the destruction of buffalo herds – their primary food source and way of life. From the Native American perspective, the actions of European Americans appeared irrational and destructive, not only to their cultures but also to the natural environment.

James Mooney recognized the mischaracterization of the Ghost Dance in the press. He undertook extensive research, publishing his findings in a report in 1890 and later in a comprehensive book in 1896. Mooney aimed to dispel inaccurate and prejudiced portrayals of the Ghost Dance, emphasizing its peaceful nature. His fieldwork from 1890 to 1894 involved extensive travel and engagement with numerous tribes. As a participant-observer, he actively engaged in Ghost Dance ceremonies with the Arapaho and Cheyenne, consulted with movement participants, and documented his experiences through photography. The Ghost Dance fascinated ethnographers as a rare instance of a new religion rapidly developing and transcending cultural and linguistic boundaries.

Mooney traced the Ghost Dance beliefs to earlier prophecies across various Native American groups predicting the restoration of their lands and traditional ways of life, dating back to the early periods of European colonization. Thus, the Ghost Dance, while seemingly sudden in its widespread emergence, drew upon long-standing hopes and beliefs within Native American cultures.

A group of dancers in Native American dress form a circle around an American Flag.

A group of dancers in Native American dress form a circle around an American Flag.

“Ghost dance – Cheyennes & Arapahoes,” ca 1898. Alt text: Circa 1898 photograph of Cheyenne and Arapaho Ghost Dancers circling an American flag at the Indian Congress in Omaha, Nebraska.

Tragedy at Wounded Knee

The Ghost Dance became tragically linked to the Wounded Knee Massacre, one of the most devastating events in American history. On December 15, 1890, tensions surrounding the Ghost Dance led to the killing of Chief Sitting Bull by police at Standing Rock Reservation. Following this, a group of over 300 Miniconjou Lakota, led by Chief Spotted Elk (Big Foot), sought refuge at Pine Ridge Reservation. However, they were intercepted by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee Creek.

On December 29, 1890, the Lakota were surrounded and disarmed by soldiers, including units equipped with Hotchkiss guns. As weapons were being confiscated, gunfire erupted. The details remain disputed, but the ensuing massacre resulted in the deaths of an estimated 150 to 300 Lakota, many of whom were unarmed women and children. Chief Spotted Elk, ill with pneumonia and unarmed, was among those killed. Army casualties numbered 25.

Mooney provides a detailed account of the events leading up to, during, and after the Wounded Knee Massacre, including firsthand testimonies and investigations. He attributed discrepancies in death toll figures to the exclusion of those who died from wounds and exposure after the immediate conflict, estimating the total loss of life at around 300.

Despite the horrific nature of the event, it was initially portrayed as a “battle,” and soldiers received Medals of Honor. The shift in public perception began with Dee Brown’s 1971 book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, and the rise of the Native American civil rights movement. This marked a turning point, bringing Native American perspectives on history to the forefront.

The body of Spotted Elk (Big Foot) after the Wounded Knee Massacre, 1890. Alt text: Black and white photograph of the body of Chief Spotted Elk lying in the snow after the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890.

Legacy and Continued Relevance

Mooney’s research and publications, including his Ghost Dance song recordings, were intended to promote understanding and prevent further violence in the aftermath of Wounded Knee. However, popular perception at the time largely framed the Ghost Dance as a dangerous threat that was decisively ended at Wounded Knee. The Bureau of Indian Affairs even attempted to ban the practice, further reinforcing this idea.

In reality, the Ghost Dance continued to be practiced into the early 20th century, and its songs remain part of Native American traditions today. The collections of the American Folklife Center hold further examples of Ghost Dance songs (available on site), sometimes cataloged as “new religion songs.”

The legacy of Wounded Knee and the Ghost Dance continues to resonate. The 1973 Wounded Knee protest by the Lakota Sioux, part of the broader Indian rights movement, underscored the enduring significance of these events for Native Americans. The principles of peaceful resistance to injustice and oppression, inherent in the Ghost Dance spirituality, remain relevant in contemporary expressions of Native American rights and activism.

Listen to the recordings of Ghost Dance songs and consider the complex history and enduring spirit of this movement.

Notes

[1] Mooney, James. The Ghost-dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890. Fourteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1892-93, Part 2. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1896.

[2] Mooney, James. The Ghost-dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.