As a dance content creator, I’ve been immersed in the academic and practical world of dance, teaching college courses and running my own dance education business. This deep dive has sparked considerable thought, especially concerning dance forms beyond the typical ballet and modern dance focus. This reflection is leading to the development of a new college survey course exploring the vast landscape of dance traditions that exist outside the mainstream Western concert dance canon.

Naming this course proved to be a challenge. Terms used to categorize non-European and American concert dance often fall short. “Ethnic Dance” feels outdated and creates a sense of otherness. “Folk Dance” is too narrow, excluding concert, religious, and classical dance forms. “Traditional Dance” raises the question of what truly defines tradition. Even “Vernacular Dance” doesn’t encompass classical forms like Bharatnatyam, which, while rooted in tradition, are now largely taught in academies rather than solely through community and family lines.

This terminology puzzle extends to the belly dance scene. There’s often a missing link in understanding when discussing learning from dancers of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) origin, naming steps, tracing lineages, and professional performance. Specialists in vernacular dance sometimes accuse concert and classical dance practitioners of cultural appropriation, misrepresentation, or romanticized interpretations. While these accusations can be valid, I believe the core issue often lies in a misunderstanding of the diverse contexts in which dances are performed.

Essentially, the belly dance seen on professional stages, while inspired by folk and vernacular forms, evolves into a distinct concert dance genre in its own right.

This article draws significantly from the extensive research of Dr. Anthony Shay, whose work examines the transformation of vernacular and folk dance for the concert stage. I am deeply indebted to his scholarship. I also acknowledge the insights of Dr. Christopher Smith, whose research focuses on the history and reconstruction of hybrid vernacular music in the United States. Furthermore, the seminal work of Joann Keali’inohomoku, particularly her essay reframing ballet as an ethnic dance form, is a crucial influence.

A note on pronouns: Throughout this piece, I occasionally use “she” when referring to professional belly dancers. This is not intended to suggest that only women can be professional dancers, but rather reflects that the iconic professional dancers I reference—figures like Fifi Abdo, Mona El Said, and Nadia Gamal—are indeed women.

The Importance of Terminology

Before proceeding, let’s define some key terms:

Folk dance is simply defined as dance of the “people.” These dances are characterized by their informal structure, evolving over time, and often performed in groups. They typically occur during holidays or celebrations but are not religious, devotional, or taught in formal academies. Examples include the maypole dance, Morris Dance, and Lebanese debke. However, the term “folk dance” has also evolved. In the mid-20th century, professional folk dance companies emerged, such as the Reda Troupe of Egypt, Bayanihan Philippine National Folk Dance Company, and Ballet Folklórico de México de Amalia Hernández. These companies adapt dances for stage performance, removing them from their original celebratory and community contexts. Dr. Shay points out that these companies often present staged versions of “peasant” or non-urbanized cultures. In doing so, they create what he terms “invented tradition,” crafting new performance forms based on folk roots.

Vernacular dance encompasses dances performed in everyday settings: homes, parties, gatherings, and clubs. It’s the dance of “ordinary people,” without the rural connotations sometimes associated with “folk.” Dr. Smith explains that vernacular skills—including dance, music, cooking, and sewing—are learned through imitation, often guided by peers or elders. Vernacular dances are performative in nature but are not performances in the formal sense. Dancers are observed by those around them, typically friends, family, and community members. While vernacular dance can be staged (consider the evolution of Vogueing), its essence lies in its informal, community-based origins.

Ethnic dance emerged as a term in the mid-to-late 20th century to categorize non-Euro-American concert dance. Essentially, it became a catch-all for any concert dance form not derived from ballet, modern/post-modern/contemporary dance, performance art, or Broadway/commercial jazz dance – what was often considered “white” concert dance. Ethnic dance is meant to reflect the aesthetic and cultural values of a specific ethnicity and can include folk, vernacular, concert, religious, and devotional forms. Festivals like the San Francisco Ethnic Dance Festival showcase this diversity, featuring everything from Regency-era partner dances to Appalachian clogging, flamenco, Cambodian dances, belly dance/ raqs sharqi, Tahitian Ori, Hawaiian Hula, and Philippine Tinikling. However, the term “ethnic” has become problematic. Today, it often broadly means “anything that’s not ballet or modern,” often with a wider societal implication of “anything that isn’t white.” Like “belly dance,” “ethnic dance” is an imperfect, colonial-era term that is increasingly seen as antiquated and inaccurate. As Keali’inohomoku famously argued, the label “ethnic” can even be applied to ballet itself, highlighting the cultural specificity inherent in all dance forms.

Concert (and staged) dance is defined by its presentation as a professional performance. Ballet and modern/contemporary dance are prime examples. Concert dances are typically performed on a proscenium stage in theaters, with audiences seated in rows facing the stage, often paying for tickets. Performances can range from full-length productions (like Suhaila Salimpour’s Enta Omri) to shorter pieces presented in festivals. The folk dance companies of the mid-20th century exemplify the staging and transformation of “traditional” dances for the concert stage, blurring the lines between concert dance and vernacular/folk dance.

Belly dance, for the purposes of this discussion, refers to the professional, staged, evening-length performances popularized by dancers such as Nagwa Fouad, Mona El Said, Fifi Abdo, Nadia Gamal, Sohair Zaki, Dina, Randa Kamel, and Suhaila Salimpour. These performances typically occur in nightclubs or hotels and feature live musical ensembles. This performance style can be traced back to the Casino Opera founded by Badia Masabni in the 1920s. While terms like raqs sharqi or “oriental dance” are sometimes used, experienced practitioners often note that no single term fully captures the breadth and complexity of this dance form.

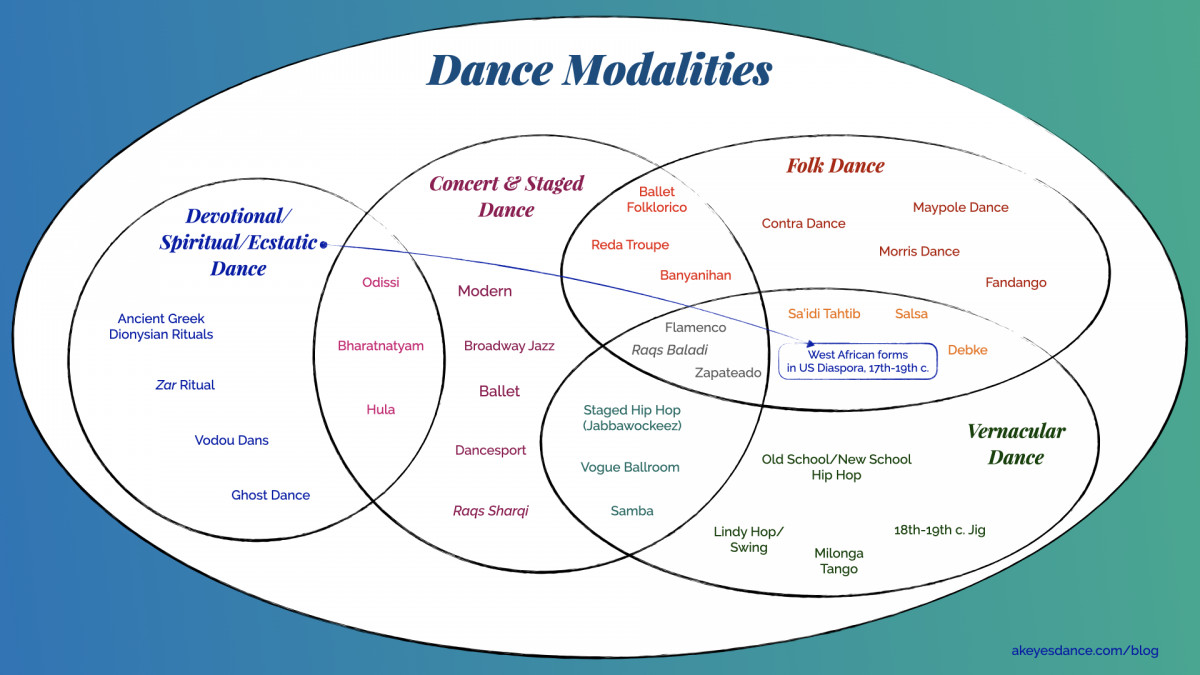

Dance Modalities Diagram: Exploring Folk, Vernacular, Ethnic, and Concert Dance Classifications

Dance Modalities Diagram: Exploring Folk, Vernacular, Ethnic, and Concert Dance Classifications

An incomplete analysis of various dance modalities with examples.

The Transformation of Folk and Vernacular Dance on Stage

When folk or vernacular dance is moved to a concert stage, significant transformations are necessary. Folk dance is inherently a community activity, performed by and for the community itself – an in-group activity for an in-group audience. However, when a director stages it, the dance becomes a representation, an ambassador for an entire culture or ethnicity – performed by an in-group for an out-group.

Here are key shifts that occur when staging folk and vernacular dance:

- Shift in Audience Relationship: The fundamental relationship between dancers and audience changes. Instead of dancing with and among friends, family, and community, dancers now perform for an audience. The very act of staging creates a separation, establishing a defined “downstage” and a performer-audience divide. Even if the staged form is derived from folk/vernacular traditions, the presence of a theater setting inherently creates an in-group (performers) and out-group (audience). The dynamic of who is performing for whom and why is fundamentally altered.

- Choreography and Rehearsal: Most folk dances presented on stage, or even at cultural festivals, are choreographed and rehearsed. Companies aim for consistent performances with set sequences of movements, staging, and blocking. Rehearsals typically take place in dance studios or cultural centers, moving the dance from spontaneous community expression to structured, repeatable performance.

- Formal Training: Dancers in companies presenting staged folk and vernacular dances generally undergo formal training. They take classes from master teachers and choreographers, spending considerable time in studio settings to learn technique, steps, and choreographies. Staged forms often incorporate virtuosic elements, such as impressive leaps, fast turns, or complex footwork, enhancing the performance aspect.

- Costume Design and Stylization: Costuming becomes a critical element. Directors make deliberate choices about costume styles, colors, makeup, and hair styling. Stage costumes are rarely exact replicas of everyday wear from specific regions or time periods. Instead, they are often stylized and enhanced with vibrant colors, rhinestones, sequins, and elaborate decorations, adapted for stage visibility and the demands of dance movement.

- Music Selection and Adaptation: Directors must carefully select music or commission original scores or re-recordings. If live musicians are involved, their performance must also be consistent across shows. Music choices, musicians hired, and song arrangements are all aesthetic, political, and creative decisions that further transform “people’s dance” into “professional dance.”

A typical stage with wings and lighting, and an orchestra pit, illustrating the physical separation between performers and audience characteristic of concert dance.

Belly Dance: Blurring the Lines Between Vernacular and Concert

Professional belly dance, often known as raqs sharqi, uniquely blurs the lines between audience and performer, and between vernacular and concert dance forms. The classic belly dance performance, featuring a soloist with a live band, integrates elements distinct from typical Euro-American concert dance presentations.

- Audience and Musician Interaction: Unlike the proscenium arch separation of many concert dance forms, belly dancers frequently interact directly with both the audience and the musicians. This interaction mirrors a jazz singer’s engagement in a supper club. Audience members might approach the stage to offer tips or even briefly dance with the performer, creating a more participatory and less formally structured atmosphere.

- Stage Proximity and Setting: Classic belly dance, from its origins in venues like the Casino Opera to contemporary 5-star hotels in Cairo and Dubai, is typically not performed on a raised proscenium stage. Nightclub stages are often at the same height or level as the audience, minimizing the architectural separation common in traditional theaters. While belly dance is increasingly performed on proscenium stages, its historical and quintessential presentation remains in nightclubs with live bands.

- Improvisation and Adaptable Choreography: Dancers often improvise movements, though their deep familiarity with the music allows for a kind of fluid, adaptable choreography. Solo performances are generally not rigidly rehearsed or set, emphasizing spontaneity and responsiveness to the music and audience.

- Performance-Based Skill Development: Historically, many renowned belly dancers developed their skills through performance experience itself, rather than solely through formal studio training. They honed their craft on stage, learning by doing. This has evolved since the 1970s, especially with more foreign-born dancers entering the nightclub and hotel performance circuits in Cairo, Dubai, and other cities within the MENAHT region.

- Musical Improvisation and Collaboration: Musicians in belly dance settings also incorporate improvisation, through solo taqasim and heterophonic embellishments. They might adjust song phrasing or even spontaneously change the setlist, creating a dynamic and collaborative performance environment.

These characteristics position belly dance/raqs sharqi/oriental dance in an intermediate space between Euro-American concert dance and vernacular dance.

In this iconic performance setting, Nadia Gamal, her orchestra, and the audience are all situated on the same physical plane, highlighting the integration between performers and audience.

“Folkloric” as a Stand-in for “Peasant”

It’s important to distinguish between “folklore” as an academic field and “folkloric dance.” Folklore is a broad discipline encompassing the study of diverse cultural elements of “common people,” who can be both urban and rural. However, when staging “traditional” dances, “folk” and “folkloric” often become euphemisms for “peasant.”

In belly dance performances, a “folkloric tableau” might be incorporated, featuring songs or segments with “peasant” elements. These elements often draw from balad (Arabic for “countryside”) or fellahin (Egyptian agricultural laborers, or peasants) traditions.

The baladi tableau typically appears in the latter part of a belly dance show. The dancer changes from her bedlah costume into a baladi dress, galabiyya, or a dress made of assyut or tulle bi-telli fabric, quintessential baladi materials. She might be accompanied by “back-up” dancers, often young men in galabiyyas who perform simple, choreographed phrases with tahtib sticks. The music often features baladi songs or Sa’idi pieces with tabl baladi drums and a mizmar (a double reed wind instrument), instruments associated with fellahin culture, or even more contemporary sha’abi songs.

In contrast to the previous example, Nadia Gamal here wears a stylized baladi dress for a folkloric tableau, demonstrating the adaptation of folk elements for stage performance.

These folkloric presentations exemplify the “invented tradition” in staged folklore described by Dr. Shay. The intent is not to authentically replicate fellahi or baladi dance as seen in rural Egyptian villages. Instead, dancers portray a character, often bint al-balad, the “country girl,” an archetype simultaneously innocent, playful, flirty, and assertively feminine, who might playfully interact with masculine farmer figures using an assaya (cane) or tahtib stick. The bint al-baladi is an archetype, sometimes bordering on stereotype, rather than a realistic representation of rural life outside Luxor. She is, in a sense, a romanticized fantasy of peasant life.

Conversely, the first part of a belly dance show, with its grand entrance song—often composed in the style of Hani Mehanna’s “Misha’al” or Muhammed Sultan’s “Set al Hosen”—is distinctly urban, embodying glamour, sophistication, and class. The dancer, impeccably styled, in an expensive costume, and with perfect grooming, embodies professional artistry. She is a diva, a superstar. Her entrance, often with a flowing chiffon veil, declares, “Yes, I am a belly dancer, aware of your judgments, but I am elegant and untouchable. I am not a country girl.”

Nagwa Fouad’s entrance to “Set al-Hosen” (on a soundstage) perfectly captures the diva persona, emphasizing the sophisticated and urban aspects of professional belly dance.

Belly Dance as a Form of Concert Dance

Returning to the definition of vernacular dance as learned through observation and imitation, it’s clear that most belly dance learning contexts today differ significantly. Most students are not learning belly dance by attending Arabic or MENAHT parties or weddings, imitating participants, absorbing cultural nuances, and receiving informal guidance from community members. For those outside MENAHT heritage, growing up dancing to Arabic/MENAHT music at home or family events is not the norm. Furthermore, the bedlah costume, iconic in belly dance, is not worn in vernacular settings at parties or homes within the MENAHT region. The bedlah is specifically associated with the professional dancer, marking her profession.

Belly dance/raqs sharqi as it is learned, performed, and taught globally today—in the United States, Europe, and beyond—is not accurately categorized as folk or vernacular dance. It more closely resembles a classical dance form, akin to bharatnatyam, certain flamenco lineages, and indeed, ballet.

Students attend classes in studios, pay instructors (ideally those with cultural heritage or direct mentorship from someone within the culture), learn movements and steps in structured, progressive sequences, and practice combinations designed for skill development. Student showcases, “haflas,” and festivals are held in dance studios, theaters, and hotel ballrooms, primarily for non-MENAHT audiences.

Whether intentionally or not, belly dance, regardless of terminology preferences, has moved far from its folk and vernacular roots, evolving into its own distinct field.

This evolution does not diminish the importance of understanding its origins, exploring its roots, and acknowledging its diverse influences.

However, to insist that stage belly dance remains a folk or vernacular form overlooks the transformative journey initiated nearly a century ago by Badia Masabni. It is now a staged dance, a type of concert dance, practiced and presented for paying audiences.

Therefore, as students and practitioners, it’s crucial to recognize the dedicated work, skill, and training inherent in performing belly dance on the concert stage, whether in festivals, restaurants, nightclubs, or traditional proscenium theaters.

Notes

-

The term “white” is intentionally placed in quotation marks to acknowledge its socially constructed nature, particularly when discussing folk and vernacular dances. There isn’t a singular “white” dance tradition. Instead, there are diverse dance traditions from specific regions like England, Scotland, Ireland, France, the Basque region, and Italy. Furthermore, modern European borders don’t fully capture the rich diversity of traditions within the continent; cultural markers in Sicily differ significantly from those in Milan, despite both being within “Italy.”

-

Many foreign-born dancers, particularly those from Russia and Ukraine performing in Cairo and other Arab cities, often have ballet backgrounds from childhood. They then seek specialized training in “oriental dance” from former members of renowned folkloric dance companies such as the Reda Troupe and Firqat Khawmiyya, highlighting a fusion of concert and traditional dance influences in their professional development.

-

This generalization about “folk” equating to “peasant” is not universally applicable, especially considering the character dances created by Mahmoud Reda for his company. His work often depicted urban characters, such as the milaya leff dance portraying a young urban woman from Alexandria and the bambutiyya featuring a boisterous sailor from Port Said, illustrating a broader representation of Egyptian society beyond just rural peasantry.