Our Cuban adventure was drawing to a close, but the final day in Havana was rich with experiences, starting with a captivating lecture at the Centro de Estudiantes Martianos. The topic? The vibrant world of Cuban sports and its deep-seated culture. Our speaker, a passionate sports commentator, delved into the fascinating history of Cuban athletics. Before the Revolution, Cuba wasn’t globally recognized for sporting prowess. However, under Castro’s regime, sports became a national priority, a strategic avenue to assert global standing. Olympic medals were seen as symbols of national strength and prestige, crucial for a newly independent Cuba eager to showcase its power on the world stage. From 1959 through the mid-1960s, Cuba’s intense dedication to sports became undeniably successful, with victories across various disciplines. A significant moment arrived in 1964 when runner Enrique Figeroa secured second place against the United States in the 100m sprint at the Tokyo Olympics, marking a pivotal moment in Cuban sporting history.

This history of Cuban sports is often framed as an inspiring underdog narrative, portraying Cuban triumphs over powerful American influence, each victory reaffirming their hard-fought independence. Initially, this perspective on America felt a bit jarring. However, this viewpoint resonated with themes we encountered throughout our academic exploration of Cuba. The Cuban motivation for sporting success was particularly intriguing. From an American perspective, sports often revolve around global dominance, aiming to outperform all nations, especially during the Cold War rivalry with Russia. The Cuban focus, however, seemed more localized, centered on asserting themselves against a specific historical context. It prompted reflection on America’s global role, perhaps as a dominant force that may have inadvertently overshadowed smaller nations. Despite these complex reflections, watching the highlight reels of Cuban victories was genuinely impressive, even while acknowledging my own country’s defeats within those sporting narratives.

Following the engaging sports lecture, we dispersed into smaller groups for our last independent lunch in Cuba. I joined Brittany, Emma, and Jennifer, and we found ourselves returning to La Catedral, the same paladar where we had dined on our very first day. There was a sense of poetic symmetry in beginning and ending our Cuban culinary journey at the same restaurant. Upon arrival in Cuba, I had been quite anxious about dining out due to dietary restrictions, half-expecting to fall ill within days, especially after being limited to salad on that first lunch. Yet, by this final lunch, my initial apprehension had transformed into confidence. I comfortably ordered steak, quite a departure from that first salad! It turned out to be a delightful meal. We savored delicious food, reminisced about our experiences during the trip, and even managed to spend our remaining CUC on flan. This meal, in a way, felt like our own version of a celebratory dance, a joyful culmination of shared experiences, not unlike the vibrant energy of Dirty Dancing 2, a film that, while set in Cuba later on, captures some of that passionate Cuban spirit and rhythm.

Cuba 1794

Cuba 1794

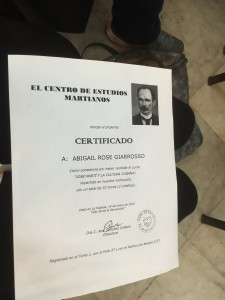

After our satisfying lunch, we reconvened at the CEM for our graduation and certificate ceremony, marking the successful completion of our two-week course on Jose Marti and Cuban culture. Another study abroad group, from Worcester State, also received their certificates alongside us, and we shared our experiences with one another. Jake, from our group, volunteered to speak, eloquently expressing our collective enjoyment of the trip and how it had offered us a unique, immersive perspective of Cuba. Professor Julian also delivered a thoughtful speech, emphasizing the leap of faith inherent in international travel and expressing his pride in our contributions to fostering warmer Cuban-American relations.

Cuba 1801

Cuba 1801

My personal highlight of the ceremony, aside from the celebratory sparkling cider that followed, was the closing address by Ana Sanchez Collazo, the director of the CEM. She encouraged both student groups to continue exploring the teachings of Jose Marti and Cuban history upon our return to America. She urged us to share the truths we had witnessed about Cuban culture, both positive and challenging, fostering honest dialogue. Her words resonated deeply, suggesting Cuba’s desire for a more open and honest relationship with the United States, built on trust and understanding between individuals, like us students, acting as cultural ambassadors. Director Collazo concluded her speech with the powerful CEM belief that culture should transcend borders. It felt like an invitation to actively engage with Cuban culture even back home in America, to see it as an extension of the authentic experiences we had gained on this trip. In a way, it instilled a feeling that a part of Cuba could remain with me, a tangible takeaway carried not just in my luggage, but in my heart and mind.

Cuba 1802

Cuba 1802

After the ceremony, we returned to our residencias, enjoying some precious free time before our API dinner and dance event. Most of us opted to begin packing, a task interrupted by the kind offer of tea from our wonderful host, Carlos. The six of us girls residing in the residencia gathered in the familiar sunroom, our usual evening gathering spot, and shared fond memories of Cuba with Carlos, reflecting on our collective experiences. Carlos generously offered to show us his rooftop garden, a space he clearly took immense pride in. Unbeknownst to us, right above our heads throughout the trip was a charming rooftop oasis, boasting the most breathtaking panoramic view of Havana I had encountered in the past two weeks. A delightful shaded patio, surrounded by lush greenery and offering a 360° vista, was simply stunning. It was evident how much personal care and effort Carlos invested in his rooftop sanctuary.

Cuba 1818

Cuba 1818

Cuba 1823

Cuba 1823

Later, we rejoined the Worcester State group at the main residencia and traveled together, a large Massachusetts contingent, to a special restaurant. There, we put into practice all the cultural skills Cuba had taught us. We savored authentic mojitos, confidently showcasing our salsa steps – perhaps not quite Dirty Dancing level, but enthusiastic nonetheless! We patiently waited for our meals, a lesson in Cuban time. We joined in singing with the lively band, belting out familiar tunes like “Hotel California” and “La Bamba”. Some even tried Cuban cigars. Finally, we enjoyed our delicious farewell meals. It was a truly memorable send-off, filled with laughter and goodbyes to many familiar faces, including Ana, our invaluable translator throughout the trip.

Returning to the residencia for the final time, a wave of nostalgia washed over me. It was a unique and fleeting moment, being in Cuba at this particular time of thawing relations, anticipating increased American tourism, and enjoying the pleasant January warmth. When would I again feel the gentle midnight breeze of the Malecon? Would I ever see Old Havana again? I craned my neck, gazing out the bus window, trying to capture one last glimpse of Cuba before our departure back to America. It struck me then, how Jose Marti sparked a revolution in Cuba from afar, and how Hemingway was forever changed after his time in his Cuban home. It seemed incredibly difficult to lose the passion for Cuba once you had experienced its culture firsthand. Director Collazo’s philosophy, that culture knows no borders, became a source of comfort in my moment of farewell sadness that night. While physical return to Cuba might not always be possible whenever we longed for it, we could always access the feeling of being in Cuba, of being present in the moment, through cultural practices and cherished memories.

[