“I wanna dance with somebody, with somebody who loves me,” the iconic words of Whitney Houston resonate deeply when I declare, “I am inside somebody who loves me.” This isn’t just a catchy tune; it’s a profound desire to embrace oneself, and poetry becomes the dance floor where this intimate connection unfolds. This declaration is a deliberate step away from the sentiment expressed by Amiri Baraka in his poem ‘An Agony. As Now,’ where he wrote, “I am inside someone / who hates me.” No more. Today, we refuse self-hatred. We reject the methodical self-sabotage, the painful journey of navigating identity through a lens of self-loathing. The shrill cry of militancy, once a shield against our own feelings of helplessness, is replaced by a powerful affirmation: I am inside somebody who loves me. This inner self is a fierce protector, a creator who uses words as weapons against the darkness that seeks to consume those trapped within self-hatred.

This is not a universal truth, but a declaration of personal liberation. To love oneself, particularly within a marginalized identity, can feel like a radical act. In a world that often projects hate and negativity, self-love can appear as a defiant stance – a form of insanity to some, or an electrifying force of life to others. It’s a precarious position, charged with both vulnerability and immense power.

From this foundation of self-love, can poetry be choreographed? Can it be improvised like a dance? Perhaps, if we consider the poem as a living entity, inhabited as deeply as our own bodies. Each word, each sound, becomes a movement within a system, navigating space and time with purpose. Words populate a vision, testing its limits and defining its boundaries in the very act of expression. When a poem is nurtured by a syntax that loves it, it moves with the inherent grace and strength of a spinning dancer. However, conflict arises when this self-love is articulated through a language that seeks to diminish or deny it. If the language demands conformity to its broken structures, forcing us to adopt its hesitations and flaws, a battle ensues. This is a rebellion against the false promises of language that fails to capture our truth, a revenge for the memories that wither in the shadows of namelessness.

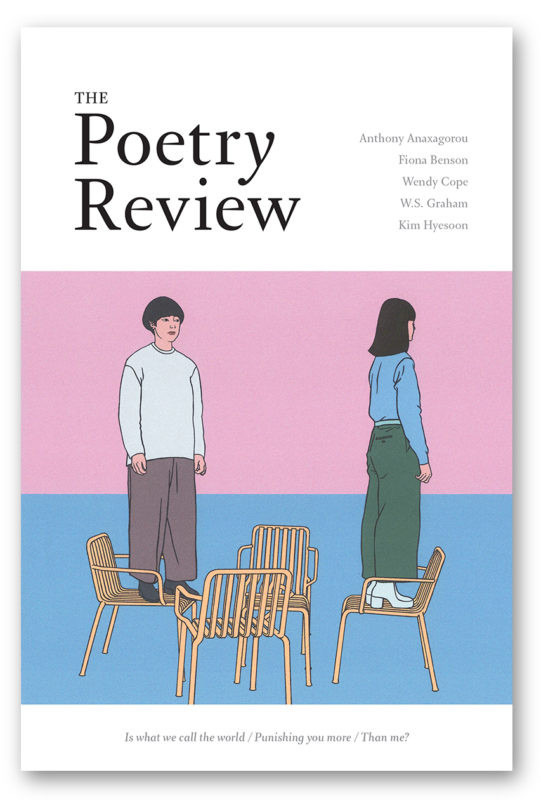

The Poetry Review Spring 2018. Cover by Manshen Lo.

The Poetry Review Spring 2018. Cover by Manshen Lo.

Somewhere between the self that loves and the language that attempts to exploit our vital energy lies a space for intention, for linguistic disobedience that ultimately serves that initial love. It is in this crevice that poems ignite, expanding into sanctuaries of self-expression. The poems that resonate, the poems we yearn to write, seize the joy of this space as a form of poetic justice. They reach out with both fury and tenderness, grasping for both new and ancient expressions, reclaiming voices silenced by colonialism. Across the African diaspora, we see an unapologetic embrace of improvisation, of “speaking in tongues,” of dance as a form of expression, and of spiritual practices that legitimize these forms. Jazz music, canonized into a secular art form, embodies this spirit of improvisation that the colonizer’s mind can then safely admire. What we are witnessing is a sophisticated poetics of refusal, so ingrained it appears almost folkloric. Bodies resist the rigid codes of Western language and logic, both in thought and form. Poetry, alongside our physical presence, becomes a potent tool of resistance, a powerful form of reproof.

This is not a declaration of war, but an affirmation of self-love. We prove this love through the way we speak – of ourselves, to ourselves, and through ourselves – and by the linguistic rules we consciously break. In this system, not of hierarchy but of interconnectedness, our movement through space and time, our relationship with our bodies, our self-worth, our freedom, and our eagerness for self-knowledge all shape our thinking. These thoughts then manifest in our lived experiences, especially when they transcend mere feeling and become spoken language. The internalized low self-esteem that can sometimes accompany marginalized identities is evident in the mimicry of colonial languages and forms. As we evolve towards new, hybrid poetic textures that mirror the authentic rhythms of our thoughts and the highest potential of our actions and rituals, we move away from self-hatred and towards self-love. This love, this self-acceptance, becomes our primary duty. To act in a manner worthy of this love is paramount.

Therefore, we write in our complex and compelling languages – be they Latinate, Romance, or patois – how we desire to appear, feel, sound, and exist. In this vulnerability, if the result is deemed “ugly,” then the fault lies collectively. But if beauty emerges, we are reborn, orphaned from limiting definitions, children of boundless potential once more. Our poems become instructions, and every person who has experienced colonization becomes a poet the moment they wield language against itself, dismantling its oppressive structures to embody their own truth. We crave poems that embody this power, and a world that eagerly welcomes and demands them. You might write of ordinary lives – laborers in a field – but infuse it with a raw, unfiltered honesty, allowing for vulnerability and complexity. Blackness inherently defies Western logic, and so must the poems born from bodies that love themselves enough to expose this untamed interiority. Hip-hop, with its innovative use of language and rhythm, is already leading the way in this liberation. Literature is catching up, carrying love poems as powerful cargo, pushing boundaries, being reborn, falling in love with ourselves in the vast emptiness of alienation, where everything becomes familiar and ripe for liberated expression. It is akin to the transformative moment of seeing yourself through loving eyes for the first time, a realization of inherent beauty that cannot be undone by doubt. Poetry captures this moment of enchantment, and its boundless, unpredictable future.