In 1969, amidst the powerful currents of the civil rights movement, an artistic revolution was sparked with the creation of the Dance Theatre Of Harlem (DTH). Founded by Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook, Dance Theatre of Harlem emerged not just as a ballet company, but as a profound statement of inclusivity and a testament to the democratic spirit in dance.

Born from a moment of social upheaval and a vision for artistic equity, Dance Theatre of Harlem has become one of the most influential American ballet companies of the last half-century. Its inception story is deeply intertwined with the personal journey of its founder, Arthur Mitchell, and the turbulent times that shaped a nation.

Mitchell’s path to founding Dance Theatre of Harlem was paved with groundbreaking achievements. In 1955, he made history as the first African American principal dancer with the New York City Ballet (NYCB). As a protégé of the legendary George Balanchine, co-founder of the School of American Ballet and a towering figure in 20th-century ballet, Mitchell absorbed the highest echelons of classical training and artistry. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, served as a pivotal moment, igniting Mitchell’s determination to use his art to make a difference in his own community.

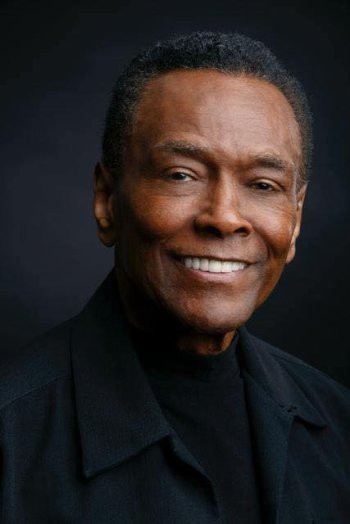

Arthur Mitchell in performance, photo by Joan Marcus

Arthur Mitchell in performance, photo by Joan Marcus

While working in Brazil on a U.S. government commission to help establish the National Ballet of Brazil, Mitchell felt an undeniable calling to return to his roots in Harlem, New York City. His vision was to offer ballet classes to local youth, creating opportunities where they had previously been scarce. At a time when the civil rights movement was reaching its zenith, Mitchell’s initiative was an act of artistic resistance, establishing a sanctuary for dancers of all backgrounds who yearned for rigorous training, performance experience, and the chance to excel in the often-exclusive world of classical ballet.

The early days of Dance Theatre of Harlem were characterized by humility and inclusivity. Mitchell began teaching in a converted garage in Harlem, intentionally leaving the doors open to invite curiosity and participation from the community. He adopted a relaxed dress code, encouraging young men, who might have felt alienated by traditional ballet attire, to join in wearing jeans and t-shirts. As student numbers grew, Mitchell partnered with his former ballet master, Karel Shook. Shook’s expertise became instrumental in running the school and shaping the trajectory of what would formally become Dance Theatre of Harlem. Together, they nurtured a company that would not only redefine the American ballet landscape but also become a global symbol for Black dancers and a champion for diversity in the arts. Dance Theatre of Harlem became a pioneer, integrating stages and disseminating the beauty of ballet through extensive outreach programs both domestically and internationally.

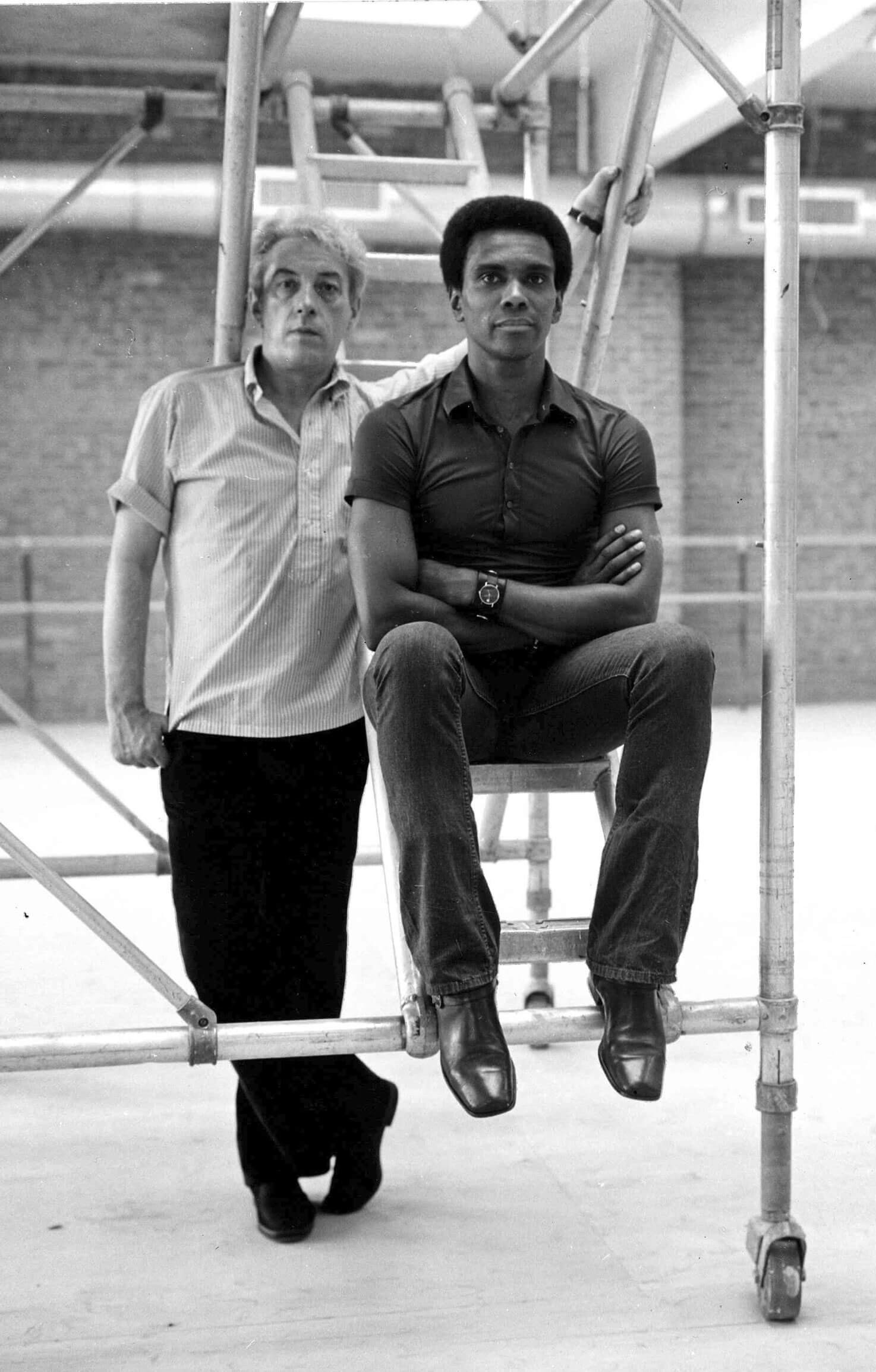

Dance Theatre of Harlem co-founders Karel Shook and Arthur Mitchell in 1971, photographed by Marbeth

Dance Theatre of Harlem co-founders Karel Shook and Arthur Mitchell in 1971, photographed by Marbeth

Virginia Johnson, a budding ballerina and NYU School of the Arts student, encountered Mitchell and became a founding member of Dance Theatre of Harlem, later ascending to the role of artistic director. Reflecting on the company’s formative years, Johnson noted, “In that first company, we were an extremely diverse group of people. We were Asian, Mexican, Black… I think the first white dancer didn’t come until 1970. But it was not about making a ‘black ballet company.’” She emphasized Mitchell’s broader intention: “It was to make people aware of the fact that this beautiful art form actually belongs to and can be done by anyone. Arthur Mitchell created this space for a lot of people who had been told, ‘You can’t do this,’ to give them a chance to do what they dreamed of doing.”

Dance Theatre of Harlem gained traction during the Black Power movement, yet, as Johnson clarifies, their approach was not rooted in aggression but in empowerment. “But there wasn’t a sense of militancy around the idea of making black people visible in this art form. It was more that he made dancers aware of the fact that they could define their own identity. That they didn’t have to be defined by somebody else’s perception of them.”

Ballet’s origins trace back to the European Renaissance and Baroque periods, evolving in the courts of nobility, particularly in France under Louis XIV. Initially an art form of and for the elite, ballet gradually became more accessible to the public. However, even as it spread from France across the globe by the 19th century, its rigorous training and elaborate aesthetics maintained a degree of exclusivity. Historically, given ballet’s early focus on European ideals and narratives, a misguided assumption arose that non-white dancers could not authentically embody or interpret this art form.

Arthur Mitchell was born in 1934 in an America deeply marked by racial segregation. This pervasive atmosphere extended into the dance world, severely limiting opportunities for dancers of color in classical ballet. George Balanchine, who would become a mentor to Mitchell, was among those who sought to broaden ballet’s reach and promote integration. In 1933, Lincoln Kirstein, Balanchine’s collaborator, envisioned a ballet company with diverse representation, even proposing a core group of dancers “half white and half negro.” This vision led to the establishment of the School of American Ballet and subsequently the New York City Ballet. However, the initial aspiration for integrated student bodies faced administrative resistance and was never fully realized in its early years.

Despite these challenges, Balanchine was committed to showcasing Black talent, inviting guest artists like Martha Graham-trained dancer Mary Hinkson and choreographer Louis Johnson to perform with NYCB.

While Arthur Mitchell is widely recognized as a pioneering Black dancer at NYCB, Arthur Bell, a lesser-known figure, preceded him as a student at the School of American Ballet in the late 1940s and performed with NYCB before building a career in Europe. Bell’s story, largely forgotten until he was found living in poverty in 1994, underscores the limited opportunities and subsequent neglect faced by many Black dancers after their performing careers concluded.

Mitchell’s own introduction to ballet occurred in Harlem. His mother enrolled him in tap classes at the Police Athletic League. A school guidance counselor recognized his potential and encouraged him to audition for the High School of Performing Arts, where he was directed towards ballet. He excelled, earning a scholarship to the School of American Ballet shortly after graduating. It was at the school that Mitchell met Balanchine, and within a few years, he was invited to join the New York City Ballet.

Johnson emphasizes Balanchine’s profound interest in Mitchell, stating, “Balanchine was interested in African-American dancers, but Mitchell was not just a dancer to him. He was the realization of an idea that Balanchine had wanted to explore. When Mitchell joined NYCB, it released something in Balanchine. He started creating some of his greatest work—a different kind of work, something he’d been wanting to do for some time.”

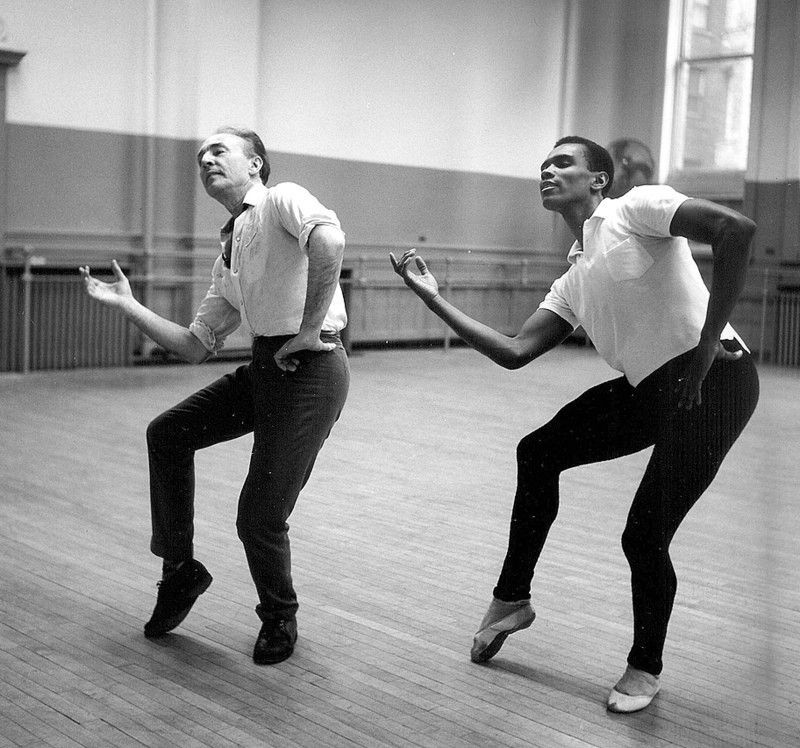

George Balanchine and Arthur Mitchell collaborating on choreography

George Balanchine and Arthur Mitchell collaborating on choreography

Balanchine choreographed roles specifically for Mitchell, most notably the groundbreaking pas de deux in Agon and the role of Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Balanchine understood the value of a dancer who brought not only technical brilliance but also personal insight to choreography.

In 1971, Dance Theatre of Harlem officially debuted at the Guggenheim Museum, heralded as a “neo-classical ballet company,” and received immediate acclaim. Later that year, Balanchine and Mitchell collaborated on Concerto for a Jazz Band and Orchestra, an unprecedented partnership that provided a significant platform for the burgeoning Harlem company. Following the success of Rythmetron, a prizewinning television special choreographed by Mitchell, Dance Theatre of Harlem launched its first full season in New York in 1974.

Mitchell’s departure from NYCB, where he had risen to principal dancer from 1956 to 1969, signaled a move away from the homogenous ballet world he had inhabited. He envisioned a more expansive realm for dancers like himself to flourish. Virginia Johnson reflects on this foundational principle: “Right from the beginning it was about diversity in the richness, which was very oppositional to the way that ballet was moving in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s in this country. At that time, ‘sameness’ was what was signified in ballet. One of the things that Arthur Mitchell was doing was creating the chance for people who had the skill—and the training—to perform, to keep challenging themselves, and to grow into world-class artists, which was not something that was happening in many other places.”

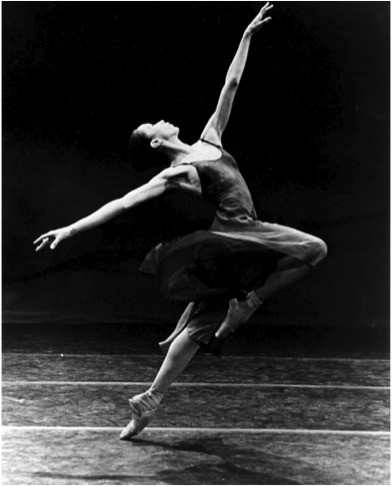

Virginia Johnson performing in Glen Tetley’s Greening; Johnson later became Artistic Director of Dance Theatre of Harlem

Virginia Johnson performing in Glen Tetley’s Greening; Johnson later became Artistic Director of Dance Theatre of Harlem

Balanchine’s generosity extended to granting Dance Theatre of Harlem the rights to perform several of his ballets, providing the nascent company with a repertoire of recognized modern classics. By 1979, Dance Theatre of Harlem was touring internationally, presenting a repertoire of 46 ballets. The 1980s saw the company ascend to the forefront of American ballet, carving out a unique space and injecting fresh dynamism into works like Firebird, Giselle, Scheherazade, Bugaku, and the seminal Agon.

Throughout the 1990s, Dance Theatre of Harlem continued to transcend racial and political divides, earning global recognition. They made history as the first American ballet company to perform in Russia after the Soviet Union’s collapse. In 1992, their tour to South Africa during the final years of apartheid sent a powerful message. Performing for integrated audiences and extending their outreach principles into townships, they established a dance program, Dancing Through Barriers, which continues to thrive today. This initiative exemplifies the profound impact a predominantly Black and Brown ballet company could have on international politics, challenging entrenched racism through the practice and sharing of their art.

Dance Theatre of Harlem Company during their historic tour in the former Soviet Union

Dance Theatre of Harlem Company during their historic tour in the former Soviet Union

After a distinguished 25-year career as a principal dancer with Dance Theatre of Harlem, and a 40-year international career overall, Virginia Johnson succeeded Mitchell as the company’s artistic director in 2013. Reflecting on her succession, Johnson shared, “When Arthur Mitchell invited me to step into his huge shoes, I really didn’t want to. But I knew that the work needed to continue.” She acknowledged the evolving challenges facing the company in the digital age: “Nowadays, we’re in an electronic age where we don’t really understand or even appreciate the notion of the live performance of an art form that is so rigorous. One that requires actually coming into the theater.”

Dance Theatre of Harlem faced a hiatus from 2004 to 2012 due to financial constraints. Johnson emphasized the impact of this period: “This means that there was a generation of little girls who didn’t see brown ballerinas. They didn’t have that seed planted of I could be up there too! I want to be a part of that! So we really need to rebuild that sense of inspiring another generation of dancers to come forward.”

Johnson has been pivotal in guiding Dance Theatre of Harlem into a new chapter while honoring its foundational legacy. Dance Theatre of Harlem stands as more than just a ballet company; it is a groundbreaking cultural institution, a living testament to the transformative potential of inclusivity in art, and a beacon of excellence.

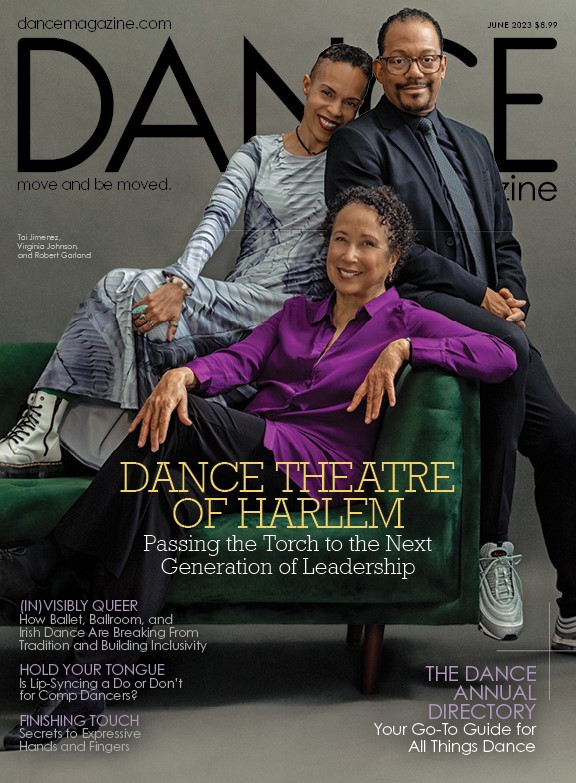

Dance Magazine cover featuring Dance Theatre of Harlem

Dance Magazine cover featuring Dance Theatre of Harlem

As Dance Theatre of Harlem concludes a remarkable four-decade chapter, Virginia Johnson retired from her role as Artistic Director at the end of the 2022-23 season on June 30, 2023. Her tenure, encompassing twelve years as Artistic Director and twenty-eight years as a company member, including her status as a founding member and Principal Dancer, marks an era of significant growth and sustained vision. Johnson transitioned to Artistic Director Emerita, and Robert Garland, acclaimed DTH Resident Choreographer and School Director, assumed the Artistic Directorship on July 1, 2023. Former DTH Principal Dancer Tai Jimenez, who made history as the first Black ballerina elevated to Principal at Boston Ballet in 2006, became the Director of the Dance Theatre of Harlem School.

Dance Theatre of Harlem continues to champion its core values of access, opportunity, and artistic excellence, moving forward into a vibrant future.

Support DTH | Join Our Mailing List