Dance Academy, an Australian TV series, unfolds within the walls of a prestigious ballet school in Sydney. Designed for a young, primarily female audience and with an eye on international appeal, it ticks many familiar boxes: iconic shots of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and Opera House, the innocent protagonist, the quirky best friend, and the archetypal mean girl. The classic love triangle also takes center stage, featuring the charming romantic interest, the brooding rebel, and the endearing intellectual.

The cast of Dance Academy: a posed photo of attractive dancers. All but one are white; five girls, four boys.

The cast of Dance Academy: a posed photo of attractive dancers. All but one are white; five girls, four boys.

The season 2 cast of Dance Academy showcases the ensemble cast of the show.

However, Dance Academy distinguishes itself through its nuanced writing, courtesy of experienced YA novelists like Melina Marchetta. The series subtly challenges genre conventions without alienating its target demographic. The “mean girl” confronts her vulnerabilities, the “goofy best friend” confronts her self-defeating patterns, and the “naive heroine” grapples with the complexities of reality.

One of the most compelling aspects of Dance Academy is its exploration of male characters. It’s essential to remember that this series is primarily aimed at young female viewers. While it’s crucial not to recenter narratives intended for women to focus solely on men, the portrayal of masculinity in teen fiction is consistently fascinating. There’s a certain irony in the way figures like Edward Cullen embody wish-fulfillment fantasies, yet often come across as shallow and one-dimensional. Dance Academy‘s male characters, while fitting recognizable molds, are placed within the intensely feminine environment of a ballet school. The series navigates this dynamic in ways that both challenge and sometimes reinforce stereotypes.

The problematic aspect arises, particularly in the initial half of the first season, from the show’s emphasis on the male ballet students’ masculinity and heterosexuality. The sole LGBTQ+ male character is a teacher, who is then replaced in the second season by a heterosexual counterpart of similar age. While this plot development is driven by narrative reasons—a student falsely accuses him of misconduct, a storyline that is problematic for various reasons, but also understandable given the student’s background—it’s still disappointing to lose a gay male role model.

The male students often appear defensive about their masculinity. Ethan voices a common complaint, “They act like we’re not athletes,” when the dance school is forced to share facilities with a football team. Christian faces criticism for insufficient core strength. It’s worth noting that female characters also express concerns about strength and fitness, but in their cases, it’s frequently intertwined with anxieties about body image, reflecting a realistic aspect of the ballet world setting.

A scene from “Best and Fairest” highlights the clash between football players in ballet attire and ballet dancers in casual clothes.

However, the series does depict gradual shifts in the boys’ understanding of masculinity. Early in the first season, Sammy, the friendly and academically inclined male character, is informed about his weak ankles and the need to strengthen them by practicing in pointe shoes. Initially, this is a source of amusement, particularly for Sammy, who has already felt his masculinity questioned due to a rooming mix-up that placed him with a girl. However, after a period of practice, only outsiders, non-dancers, find it comical. Within the dance community, it’s understood that pointe work has made Sammy a more technically proficient and resilient dancer.

A Closer Look at Sammy Lieberman

A promotional shot of Tom Green portraying Sammy, emphasizing his athleticism and grace.

Sammy is a captivating character, and Tom Green’s performance was a standout element of the first two seasons. Samuel Lieberman is burdened by his father’s aspirations for him to enter the medical profession. (“I know we don’t like to talk about it, but your grandfather was only a dermatologist.”) Coming from a traditional Jewish family with close ties to his Yiddish-speaking grandfather, Sammy is acutely aware of the perceived disappointment in choosing dance over his academic capabilities.

He also understands the societal perception of ballet as a “feminine” pursuit, a point often reinforced by his younger brother Ari, who is interested in gaming and martial arts. This adds another layer of complexity for Sammy as he attempts to convince his father of the legitimacy of a dance career, countering the stereotype of it being an easy, “feminine” choice.

Sammy eventually reconciles with the fact that he may not fit the alpha male archetype, and over two seasons, his father gradually accepts his chosen path. However, his journey of self-discovery takes another turn with the exploration of his sexuality.

The episode featuring the rugby players culminates in one of these athletes asking Sammy out on a date. This moment is significant within the Australian context, where football culture is deeply ingrained and historically homophobic. Openly gay football players are virtually nonexistent in Australia. While efforts have been made to combat racism in sports, homophobia and misogyny remain pressing issues. Depicting an openly gay footballer, even at a junior level, is a bold move for an Australian drama, particularly one targeted at young teenagers.

Sammy is visibly surprised by the invitation, becoming flustered and stating he is “not available.” This subtly reveals his relationship with Abigail to the public. The clever writing avoids a direct denial of same-sex attraction, with Sammy’s response being “I’m taken,” rather than “I’m straight.”

Therefore, it’s not entirely unexpected when Sammy later realizes he experiences attraction to men as well, specifically to his roommate and close friend, Christian. (Attraction to Christian is hardly surprising, given his magnetic personality).

What follows is a coming-out narrative that is both familiar in its themes and distinctive in its approach. While stories of “boy falls in love with boy and grapples with his sexuality” are common, Dance Academy uniquely acknowledges bisexuality.

“I have these feelings for Christian, and I don’t know if these feelings mean I’m gay,” Sammy articulates, using a metaphor about muffins and labradors to navigate the sensitive topic. Sammy fears he must choose between his perceived straight identity and his friendship with Christian.

This dilemma proves to be a false dichotomy. Sammy’s identity is far more multifaceted than just his sexuality, and while Christian doesn’t reciprocate romantic feelings, their honesty strengthens their bond.

In the second half of season two, Sammy is tutored by Ollie, a third-year student. Their initially competitive dynamic evolves into a romantic relationship. Ollie, with his inflated ego and disregard for boundaries, publicly outs Sammy by announcing their relationship to everyone.

Tara’s reaction to Sammy’s coming out is a hug and an enthusiastic, “I always wanted a gay friend!” While endearing, it’s also presented as somewhat problematic, prompting Sammy’s awkward reply, “But … I’m not…”

Sammy spends the remainder of the episode confronting two misperceptions: first, that he is exclusively attracted to men, and second, that same-sex attraction equates to femininity. The first is imposed externally, by his social circle, while the second is internalized, reflecting societal norms. Sammy doesn’t view femininity negatively, but he is aware of a culture that links male homosexuality or bisexuality with effeminacy. Having already challenged stereotypes associated with male dancers, Sammy now navigates societal expectations that attempt to redefine his identity.

Following this personal struggle, Sammy faces another challenge: his father’s reaction. Having come to terms with Sammy’s dance career, how will this traditional, middle-class Jewish doctor accept his son having a boyfriend?

Sammy, a character who strives to do right but is prone to significant missteps, asks Abigail to feign being his girlfriend, upsetting both her and Ollie. After reconciliation and apologies, Sammy’s father’s reaction is surprisingly accepting. He witnesses Sammy and Ollie holding hands, smiles, introduces himself, creating a genuinely heartwarming moment.

Tragically, this positive development is followed by Sammy’s death shortly after.

This plot point is controversial. The “bury your gays” trope is a harmful cliché, seemingly beneath the nuanced writing of Dance Academy.

However, considering Tom Green’s departure from the series—he adopted the name Thom Green and pursued roles in Halo: Forward Unto Dawn and Camp—the writers faced a difficult situation. Sammy was integral to the show’s core dynamic. Writing him out through a simple transfer to another school would have been drastically out of character, given his deep connections to his friends and his passion for dance.

A partial consolation is Ollie’s continued presence as a main character, taking Sammy’s place. While replacing a bisexual character with a gay one is not ideal, it maintains LGBTQ+ representation within the cast.

Furthermore, even into the fourth episode of the third season, Sammy’s absence is deeply felt. His friends grieve, reflect on his legacy, and adapt to a world without him. He is gone but not forgotten.

Christian: The Troubled Heartthrob

Jordan Rodrigues as Christian, showcasing his dynamic dance ability.

Ah, Christian. The archetypal Bad Boy Love Interest, the Troubled Young Man with a Past. His backstory includes the death of his mother, abandonment by his father, and an arrest for armed robbery in the first season. He is undeniably trouble, yet his undeniable dance talent earns him repeated second chances from the academy. He is also the on-again, off-again boyfriend Tara struggles to fully move on from, even into season three.

He is intensely captivating.

Full disclosure: Christian was the primary reason for initially watching Dance Academy. A glimpse of the series playing silently in a cafe, showcasing attractive teenagers, dance sequences, Sydney vistas, and actor Jordan Rodrigues, was enough to pique interest.

Another confession: Christian’s appeal partly stems from his resemblance to Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender. Despite admiration for Dev Patel, the casting of The Last Airbender remains a sore point, especially when considering Jordan Rodrigues’s potential as Zuko.

Notably, the series’ main love interest is a young Asian-Australian actor.

Australian television has historically been overwhelmingly white. While some shows actively strive for diversity, these are often adult-oriented dramas. Dance Academy, while predominantly white, is noteworthy for featuring two prominent love interests who are men of color (Ollie being the other).

(The school’s predominantly white demographic likely mirrors the reality of elite ballet institutions, but should accuracy always be prioritized in fiction? The first season briefly featured a Black extra, and later seasons introduce a clique of junior dancers led by a talented Asian dancer. However, these characters remain peripheral.)

(Returning to Christian.)

Christian embodies a range of clichés, some problematic. It’s questionable that the main Asian character is the one involved with criminal activity. (In Australia, stereotypes link gang violence with Asian youth. However, Dance Academy is far removed from gritty crime dramas.)

Christian also represents urban poverty within the cast. While Tara’s family faces financial strain, they own a farm. The majority of the cast are firmly middle class, even upper middle-class in some cases. Christian’s scholarship and upbringing in public housing (“Housing Commission Flats”) significantly shape his character, possibly more so than his race, reflecting Australia’s broader reluctance to openly address racial issues.

Christian acts as a bridge between social classes for his peers. He introduces Ethan to street dance, lending authenticity to Ethan’s hip-hop choreography assignment. (While appropriation remains a factor, researched appropriation is arguably preferable to unresearched appropriation. It also reflects the show’s casting choices, where many working-class characters are played by actors from middle-class backgrounds.)

Later, when Kat mentors a talented dancer from a disadvantaged background, Christian cautions her about the long-term commitment involved, emphasizing that it’s not a fleeting act of charity. Kat’s subsequent realization of her own privilege becomes a significant part of her narrative, handled subtly, with Christian initiating the critical perspective.

However, Christian’s background is often perceived as a liability by adults. Teachers and authority figures seem perplexed by his perceived inability to simply accept help and conform. This sentiment is sometimes mirrored by viewers: why can’t he just “get over it?”

The unspoken expectation seems to be: Why can’t he just be middle class?

This dynamic recalls the Legend of Korra fandom’s reaction to Mako, another brooding love interest. Even before Mako’s romantic entanglements, fans criticized his perceived preoccupation with money, overlooking his background as a former street kid turned professional athlete in a system that exploits “professionals.” While fan criticism directed at a problematic male character was a welcome shift, the narrative around Mako often became fixated on his financial concerns.

The desire for Christian to conform to a more palatable, middle-class ideal becomes particularly evident when he is asked to articulate his emotions. The masculine ideal of the taciturn working-class man clashes with the expectations of the school board and choreographers. Christian is repeatedly urged to verbalize his feelings, as if these authority figures seek to dissect his psyche. Since Christian expresses himself primarily through action and dance, these attempts often backfire. The voyeuristic interest in his emotions understandably makes him defensive. “You’ve experienced more than your peers,” they seem to imply, “Entertain us with your trauma, but remain under our judgment.”

In a hypothetical Dance Academy vampire AU, the school board would undoubtedly be the bloodsuckers.

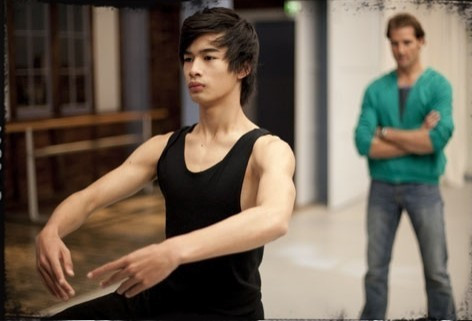

A young Asian man practices ballet, an older white man looking on from the background.

A young Asian man practices ballet, an older white man looking on from the background.

Christian in training, showcasing the dedication required for ballet.

Season two sees Christian reunite with his estranged father. The absent Asian father figure is not a common trope, and Reed Senior is less malicious than simply irresponsible. He resides on the northern coast of New South Wales, a region often stereotyped as a haven for hippies, artists, and drug users, and crafts surfboards.

The rebuilding of their relationship is a familiar narrative, executed without particular innovation. While Christian’s father is a likable character, he isn’t especially compelling. Interestingly, this quintessential “Aussie bloke” displays only mild interest and a hint of pride in his son’s ballet career, subtly subverting the typical rural Australian male stereotype. (In contrast, Christian finds common ground with Tara’s father through their shared interest in cars.)

Concluding Thoughts (For Now)

Dance Academy excels in depicting adolescence as a period of defining boundaries—emotionally, professionally, and sexually. For the male characters, growing up in a culture with rigid notions of masculinity, this involves understanding their identities as young men entering a predominantly female profession. This isn’t to diminish the female characters’ negotiation with femininity and feminism, themes frequently explored in media aimed at young women.

The series’ strength lies in addressing masculinity in multifaceted ways, largely avoiding misogynistic undertones. The storylines discussed are in addition to, not at the expense of, the female characters’ narratives. Within a series primarily targeted at a female audience, this inclusion is significant. Dance Academy strikes an unusual balance between acknowledging male struggles within patriarchal structures and avoiding the prioritization of male experiences over female ones.

Next up: Analysis of Ethan, Ollie, and Ben’s characters!