I’m spasticus, I’m spasticus

I’m spasticus autisticus

I dribble when I nibble

And I quibble when I scribble

Hello to you out there in Normal Land

You may not comprehend my tale or understand

As I crawl past your window give me lucky looks

You can be my body but you’ll never read my books

—Lyrics to ‘Spasticus Autisticus’ from Ian Dury’s 1981 album Lord Upminster

My first piece of published legal academic writing, focused on native title law, was titled ‘Two Steps Forward, One Step Back?’ Now, twenty years later, as I navigate the process of learning to walk more naturally, I find myself wondering if that title was perhaps more aptly suited to describe my personal journey. I am a law professor, a mother, and an author. Since birth, I’ve lived with a mild form of cerebral palsy. Walking has always been a challenge, which is why I find myself, at the seasoned age of forty-something, learning to walk in a way that feels more typical for the first time.

If you’re anticipating a tale of hardship designed to evoke sympathy, I encourage you to stop reading now. Firstly, I have no intention of dwelling on pain. Pain, quite frankly, is monotonous; there’s little of interest to say about it. Secondly, my reason for quoting Ian Dury’s deliberately provocative song is simple: as someone who is spastic, it makes me laugh. Dury himself was a polio survivor whose left leg, shoulder, and arm atrophied after contracting the illness at eight years old. From a young age, I felt a connection with him. I am not a victim. I am simply an individual with strengths in some areas and weaknesses in others. I am happy to be me. If granted a magic wish, addressing my lung issues would precede any alterations to my legs.

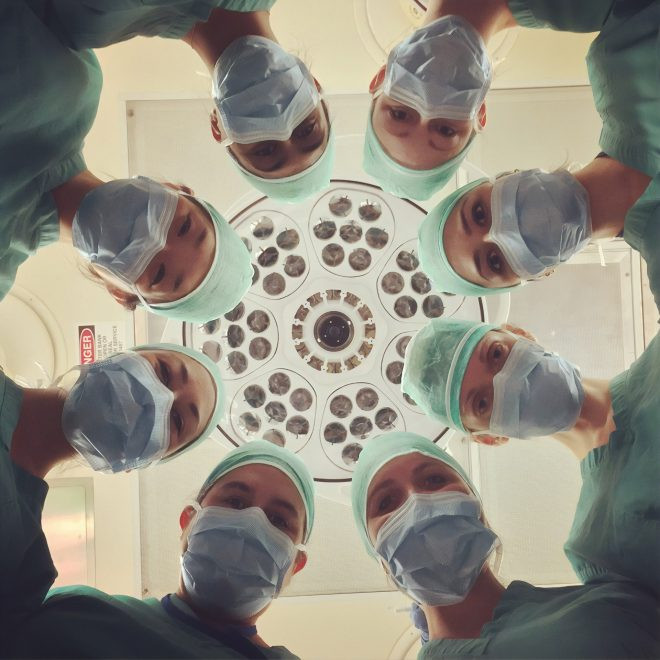

My first name is intentionally short because my survival at birth was uncertain. It’s not Katherine, Catherine, or any variation thereof. It’s simply KATY. I was born at 29 weeks, a time when infants born so prematurely often did not survive. While my mother was in labor, the medical staff advised my father to consider a name for the death certificate. The name “Katy” spontaneously came to my Dad’s mind—friends of my parents had initially chosen this name for their child but ultimately opted for Sarah instead. My dad relayed the name to the nurses… and promptly fainted outside the delivery room, requiring resuscitation. Clearly, I lived, as evidenced by my writing this account.

It must have been an agonizing experience for my parents: their first child confined to a humidicrib, untouchable. They had planned a skiing holiday. My mother had envisioned a peaceful pregnancy, relaxing by the lodge fire. Instead, she was faced with a fragile infant she couldn’t even hold. The hospital staff advised them, “Go anyway; there’s nothing you can do here.” And so, they went.

When I gave birth to my first child (two days before her expected arrival), I wept for my mother, who missed the opportunity to hold me and breastfeed me as I did my own daughter.

My grandfather described me as resembling a “skinned rabbit,” with vibrant red hair. I was small enough to fit in the crook of an arm and lacked body fat. My weight was approximately one kilogram—comparable to a bag of sugar. Initially, I lay sprawled out, much like the aforementioned skinned rabbit, but as I grew, my legs curled upwards, mirroring the fetal position. At six weeks old, I underwent my first surgery to correct a double inguinal hernia. Despite these early challenges, I was an alert and responsive infant. Unlike many infants in the ward, I eagerly anticipated my feeding tube. My mother recounts a disagreement with the matron upon my discharge, as she was reluctant to let “her baby” go, having grown deeply attached during my two-and-a-half-month hospital stay.

I was a bright and interactive child. However, when I began walking at eighteen months, I could only walk on my tiptoes. The medical professionals were initially uncertain about the cause, but we now understand it to be spastic diplegia, a form of cerebral palsy common in premature infants. The muscles in my legs are excessively tight due to persistent signals from my brain to contract, and my calf muscles are significantly shorter than average. Only recently have I come to realize that other people’s leg muscles do not experience an unpredictable tic tic tic, like a faulty clock. It has been a revelation to discover that walking is not a consciously demanding task for everyone. In my experience, without constant visual attention to my feet, their actions become unpredictable.

I still don’t dance like the other cats, in any area of my life.

How did I navigate walking as a child? Imagine standing on your toes, heels raised. Take a step without bending your knees, using a long, scissor-like motion, and push your buttocks outwards for balance. Extend your arms slightly to the sides, a little bent, with the left arm and hand dangling. Remarkably, I could walk quite quickly in this manner, and I was also capable of running, jumping, and swimming. However, riding a bicycle remains a challenge.

My parents never treated me as disabled or incapable of achieving my aspirations. I persuaded my mother to enroll me in dance classes at the age of three. We were instructed to dance like cats, which involved holding our “paws” downwards, clenched fists pointed to the floor in front of our stomachs. I found this “paw” positioning illogical. Surely, “paws” should be held upwards under the chest, palms outward, so they would be correctly positioned if we needed to move onto all fours like actual cats? I presented my reasoning to the dance teacher, but to my astonishment, she rejected my logic. I also struggled with the foot movements. At the recital, a line of well-behaved cats performed precisely as taught. However, one cat stood at the end, paws held upwards—the logical way, I maintain!—moving about in an uncoordinated fashion. “Who is that child not dancing like the other cats?” one of the other mothers inquired of my mother. My mother found herself caught between embarrassment and intense pride. I still don’t dance like the other cats, in any aspect of my life.

Eventually, I cultivated a thicker skin, a dark sense of humor, and a fascination with the terrible things people do to each other.

I learned to read at an early age. I vividly remember my sister snatching a cornflakes box from me because I was absorbed in reading the ingredient list. “Can you not stop reading for a minute?” she exclaimed. I still haven’t stopped. By the age of seven, I had read J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and my life’s ambition was to become a hobbit. Unfortunately, I am now too tall to be a hobbit, though my fondness for mushrooms persists.

It wasn’t until kindergarten that I realized my walk was unusual; before then, I had been surrounded by the unconditional love of my family. In primary school, some children called me “Spazzo,” and teachers reprimanded me for “walking like that.” Adding to the complexity, I was also academically gifted. While I am grateful that cerebral palsy did not affect my cognitive abilities, being both disabled and a “nerd” in Australia during childhood was challenging. I was a sensitive child, easily brought to tears by teasing, but I was fortunate to have good friends, some of whom remain close to this day. All that’s needed are a few kind and generous individuals. Over time, I developed a thicker skin, a dark sense of humor, and a fascination with the terrible things people do to one another. I rarely cry in public now, and I affectionately call my car the Spazzmobile, much to my husband’s dismay.

I underwent testing for numerous conditions. A muscle biopsy confirmed that I did not have muscular dystrophy but possessed an atypical ratio of short-twitch to long-twitch muscles, similar to that found in people of Aboriginal or African descent. At the time, we dismissed it as a peculiar anomaly, but we later discovered Aboriginal ancestry on my paternal grandfather’s side. Despite my ginger hair and fair skin, a part of that distant ancestor from Rockhampton lives on in my muscles.

At twelve, my orthopedic surgeon suggested lengthening my Achilles tendons—a procedure considered experimental then but now standard. My parents were hesitant, but I was determined. I was thirteen when the surgery was performed. Upon waking, both legs were encased in plaster, extending from toes to knee. My calf muscles twitched uncontrollably, so they administered Valium to alleviate the spasms. A few days post-operation, a nurse assisted me in washing my hair in a basin by the bedside. This simple act restored a sense of normalcy. I doubt she ever realized the impact of her kindness, but her face remains vivid in my memory.

Remaining self-pitying in the hospital environment was impossible, as many other children were facing far more serious conditions: the girl with spina bifida, the boy with a bone in his foot deteriorating, the hairless children battling bone cancer. Humor was a common coping mechanism among patients and nurses alike; laughter was preferable to tears. In the adjacent ward, another boy with severe cerebral palsy communicated through signs that he wanted to race wheelchairs with me. By chance, I had been given a wheelchair with unusually small wheels that day, making it a fair competition since I could barely reach the wheels with my fingers. He won and grinned at me triumphantly.

For the first time that summer, I wore out the heels of my shoes. Mum and I cried with joy.

By the end, I was thoroughly weary of the plaster casts. They were itchy, hot, and uncomfortable. But I was also apprehensive about what lay beneath: would there be large, bloody wounds? The orthopedic surgeon questioned me intently about my experience during the operation. It turned out I was the first patient capable of providing detailed feedback; the others had been non-verbal. I flinched as the plaster saw whirred and vibrated. Pink, slender lines traced my Achilles tendons—no bleeding wounds at all. Then, I hopped off the table and attempted to walk.

I fainted.

The reality was, I couldn’t walk. The surgeon recommended practicing on sandy beaches. My parents followed his advice, and I developed a somewhat normal, heavy-footed walk, my feet still feeling as rigid as if encased in plaster. The skin on my heels was initially tender, unaccustomed to pressure. For the first time that summer, I wore out the heels of my shoes. My mother and I wept with happiness.

Unfortunately, it remained apparent that something was still not quite right. In a twist of ‘be careful what you wish for,’ a girl in my Year 9 class in Australia mocked my walk. I thought to myself, “I wish you knew what it felt like to be me.” One day, in art class, while the teacher was briefly out of the room, I reached a breaking point. I stood up and stuffed handfuls of crayons down her dress. After four handfuls, I stopped, sat back down, and resumed my work. I think I frightened her. She never teased me again.

Subsequently, my family relocated to England for four years, and I saw it as an opportunity for a fresh start. My English school was small and selective. Initially, adapting was challenging as I struggled to understand the Mancunian accent, and they struggled to understand me. Crucially, however, from the school’s perspective, I excelled academically. For the first time, I stopped feeling ashamed of being intelligent and unconventional. My English school was indifferent to my lack of athletic prowess. My mother grew suspicious when I received an “A” in sports. She gave me a knowing look. “I haven’t attended sports for years,” I confessed. “I don’t think the teacher even knows who I am.” My mother laughed.

In my late teens, I heard that the girl who had teased me had been in a car accident and suffered a brain injury that affected her ability to walk. I felt no satisfaction; instead, I felt horror and guilt, as if my wish had caused this misfortune. I realized I would never wish such a fate on anyone. When I returned to Australia at 18 for university, I saw her in a supermarket, using a walker. I considered approaching her to apologize for my childish wish and acknowledge her newfound understanding of what it was like to struggle with mobility, but I was too timid. Years later, I was surprised to read a newspaper article about her in my local paper: rehabilitation had been beneficial, and I was relieved.

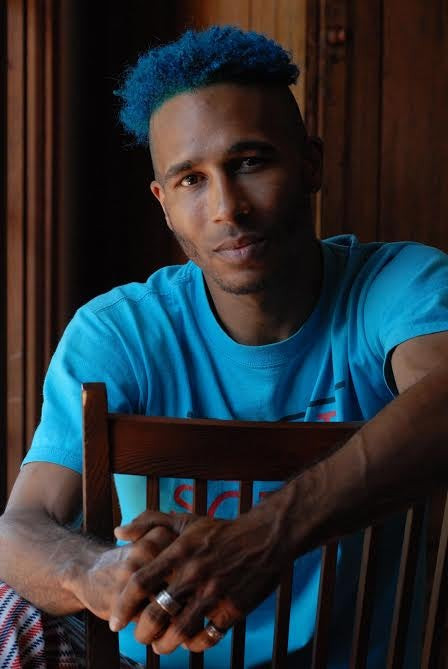

Katy Barnett

I’ve learned that there are generally considered to be three psychological responses to trauma: denial, immersing oneself in work, and emotional outbursts. My family leans towards denial and workaholism: classic Stoic, working-class approaches. I rarely discussed my physical challenges with others, neither in high school in England nor upon my return to Australia for Arts and Law studies at university. It was a sensitive subject I avoided.

There were unavoidable moments, however. I attempted to learn karate at university. I failed the first yellow belt grading multiple times. One of the instructors tried to guide me personally. After about thirty minutes, he looked at me curiously. “You move in an unusual way. Do you have a medical condition?” I quit karate.

During job interviews for clerkships at law firms, one condescending blond interviewer remarked, “You’re not a team player. You haven’t participated in any team sports.” I resisted the sudden urge to throw my glass of water at him and instead replied, “I am sufficiently aware of my abilities to know I would be a liability to any team.” My mind flashed back to primary school, to the sporting teams competing not to have me on their team. I hadn’t realized that being a lawyer involved more than just legal knowledge.

Later, another interviewer asked, “What disadvantage have you experienced?” This question felt, if anything, worse than the inquiries about my sports participation. My disability didn’t even occur to me as a possible answer until years later. It should not be a factor in hiring decisions or professional advancement. I want to be employed because of my intelligence and work ethic. Until recently, sharing these painful encounters with a stranger was difficult. I responded, “I consider myself very fortunate,” because I genuinely do.

Suffering does not always make you a better person.

It’s a fallacy to assume that hardship automatically equates to goodness or wisdom. Suffering does not invariably improve character. For some, it might enhance empathy and understanding of difficulty, though I believe—for whatever it’s worth—that I am naturally empathetic. However, not everyone responds to adversity in this way. Some seek revenge, aiming to reverse roles with those who once bullied them. I do not: I felt no joy, only distress, upon hearing about the accident of the girl who had teased me. For others, I suspect pain breeds solipsism, a preoccupation with oneself and one’s own suffering. I cope with suffering through humor and by retreating into intellectual and imaginative realms.

I married a wonderful man, and we have three children. Mentally, I didn’t perceive myself as disabled. However, I experienced several bad falls and began relying on a walking stick. Standing upright became difficult, and I was in constant pain. I gained weight and lost fitness. Someone advised me on the importance of exercise. I wanted to shout, “Do you understand how challenging that is? I can’t do the same things you can!” Then, I realized I had been deceiving myself (and everyone else) into thinking I could. In 2018, a neurologist confirmed my diagnosis of cerebral palsy and referred me to a specialist. After a year, it became evident that physical therapy alone would be insufficient. In January 2020, I began receiving Botox injections in my calf muscles, a treatment that will need to be ongoing, as it helps to reduce constant muscle contraction.

Simple acts of kindness make the world keep spinning.

It has been challenging: a week after the Botox injections, I was unable to walk for several days. I asked my daughter, “Can you explain how to walk?” She stared at me, perplexed. “It’s automatic?” No, not for me. But it has also been enlightening: the tic tic tic sensation has lessened, as has the pain. I have been learning to walk correctly. Previously, I had mimicked the walking patterns of others (imperfectly), but I didn’t realize that people actually push off with their toes or bend their knees when walking. I may not dance like the other cats, but I am learning to walk more like them, and I am experiencing significantly less pain. I am grateful for healthcare professionals, modern medicine, and the unwavering support of friends and family.

They say, ‘You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.’ This old dog is learning new tricks. She hopes this story inspires other children facing similar challenges and reminds us all, even in these isolating times, that simple acts of kindness are what keep the world turning.