Garth Brooks and Elvis Presley, two titans of different musical eras, might seem worlds apart. Yet, a fascinating anecdote and a shared connection through a powerful song reveal a surprising common ground. Back in 2007, Vancouver DJ Red Robinson, a witness to both Elvis’s 1957 Vancouver concert and Garth Brooks’ phenomenal career, made a striking comparison. He stated that Garth Brooks was the only performer he’d seen who could ignite concert crowds with the same electric fervor reminiscent of Elvis. Garth Brooks, really? For someone not deeply immersed in country music, the comparison might seem unexpected, but the sheer scale of Garth Brooks’ appeal cannot be denied.

Garth Brooks’ drawing power became undeniably clear when tickets for his Spokane, Washington, shows went on sale in 2017. A staggering 84,000 tickets vanished online in a mere 90 minutes. To put that into perspective, that’s enough to fill Spokane’s 12,000-seat arena seven times over. The overwhelming demand led to Brooks and his wife spending three days in Spokane, delivering seven sold-out performances. This level of devotion mirrors the kind of mass hysteria that once surrounded Elvis Presley.

While the energy of a Garth Brooks concert is a spectacle in itself, the connection to Elvis runs deeper than just crowd enthusiasm. It lies within the lyrics of one of Brooks’ signature songs, “The Dance.” This ballad, penned by Tony Arata, though seemingly about lost love, offers a poignant metaphor for the enduring, complex relationship between artists like Elvis and Garth Brooks, and their legions of fans. Consider these lines:

“Looking back on the memory of the dance we shared ’neath the stars above,

For a moment all the world was right.

How could I have known that you’d ever say goodbye.”

“And now I’m glad I didn’t know the way it all would end, the way it all would go.

Our lives are better left to chance.

I could have missed the pain, but I’d have had to miss the dance.”

At first glance, these lyrics might appear to be solely about romantic love lost. However, when viewed through the lens of an artist’s journey and the ebb and flow of fan adoration, a profound parallel emerges. The “dance” becomes a metaphor for the shared experience between a performer and their audience, a relationship marked by intense connection, inevitable change, and the bittersweet acceptance of time’s passage.

Like any artist with a long and evolving career, Elvis Presley experienced different phases in his relationship with his fanbase. These phases can be seen as distinct “dances,” each with its own unique energy and eventual farewells. Throughout his career, Elvis’s connection with fans unfolded in roughly five key stages.

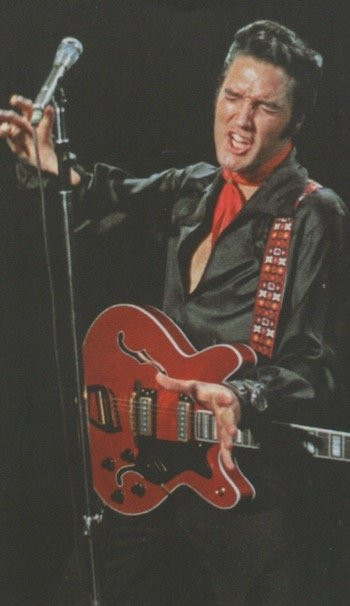

Firstly, there was the initial spark, the nascent “dance” of 1954-55. As Elvis’s star began to rise, pockets of fans emerged in the Southern towns he toured. Radio airwaves playing his Sun Records and appearances on shows like the Louisiana Hayride ignited early passions. Then came the explosion, the whirlwind “dance” of 1956-57. Elvis became a national phenomenon, captivating audiences in over 100 cities, dominating movie screens, and becoming a fixture in American living rooms through numerous television appearances.

The third “dance” began as Elvis returned from military service in 1960. He emerged a changed artist, transitioning into a more mature pop singer and movie star. This era drew in a new wave of fans, different from the screaming teenagers of his rock and roll beginnings. A fourth “dance” commenced with his triumphant 1970s comeback, marked by Vegas residencies and nationwide tours. This phase attracted a more adult audience, many of whom were rekindling their earlier Elvis devotion, alongside a fresh generation discovering his stage presence. Finally, a more subtle, enduring “dance” continues even after his passing in 1977, with new generations discovering and embracing Elvis’s legacy.

However, with each new phase, some fans inevitably fell away. Life changes, evolving tastes, and shifts in an artist’s style can lead to a parting of ways. Elvis’s two-year army service, for instance, created a significant gap. While records kept his name on the charts, his absence from the public eye was palpable. His core teenage fanbase, for whom two years felt like an eternity, naturally gravitated towards new idols like Ricky Nelson and Frankie Avalon. While these early fans might have moved on, the memory of their initial “dance” with Elvis, the intense excitement and connection, likely remained.

For those who became fans in the 1960s, like the author himself, the “dance” was different. It was the era of movie screens and pop ballads like “Return to Sender.” There was little expectation of seeing Elvis live. This generation, however, also experienced a form of “goodbye” when Elvis’s artistic direction seemed to falter in the face of the British Invasion. The rise of The Beatles in 1964 marked a turning point, and some fans felt Elvis had lost his way, retreating further into Hollywood and less impactful music. Yet, for many, the initial connection, the deep feeling of that 1960s “dance,” was strong enough to sustain their loyalty even through periods of disappointment.

The 1970s comeback era represented another shift. The “dance” this time was often with fans who were now adults, perhaps revisiting a youthful passion or discovering a new, more mature Elvis. But this phase, too, ended in a painful “goodbye.” Elvis’s declining health and untimely death in 1977 brought a different kind of disillusionment. The image of a seemingly flawless icon was shattered, replaced by the reality of human frailty. This revelation was a painful process for many fans, requiring a reconciliation between the idealized image and the flawed human being. Yet, even with this painful ending, the enduring power of his music and the memory of the “dance” – the shared joy and connection – remained.

Ultimately, the metaphor of “the dance,” as Garth Brooks so eloquently sings, encapsulates the complex and evolving relationship between artists and their fans. It’s a journey filled with exhilarating highs, inevitable changes, and sometimes, painful goodbyes. But the memories of those shared moments, “’neath the stars above,” the times when “for a moment all the world was right,” are what endure. And like the author, and countless others who have found meaning in the music of both Elvis Presley and Garth Brooks, we understand that “I could have missed the pain, but I’d have had to miss the dance.” It’s a dance worth remembering, and in its own way, worth repeating, generation after generation.