Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas is celebrated for his enchanting Impressionist depictions of ballet dancers. His artwork, characterized by soft tutus and delicate pink hues, often evokes a sense of intimate observation, as if the viewer is secretly watching from the theater seats. However, beneath the surface of glamour and youthful innocence lies a more unsettling narrative. Join us as we delve into the hidden story behind Degas’ iconic Ballet Dancer Paintings.

1870s Paris: Setting the Stage for Degas’ Ballet World

To truly understand Edgar Degas’s ballet dancer paintings, it’s crucial to consider the social backdrop of 1870s Paris. Imagine the Belle Époque, a period of peace and economic boom following the Franco-Prussian War. Paris was transforming, with new shopping arcades and a burgeoning culture of art and fashion. The magnificent Palais Garnier opera house had just opened, ready for dancers to grace its stage. Impressionism was gaining momentum, marked by the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, featuring artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and of course, Edgar Degas.

This era of progress also fostered a culture of leisure. Affluent Parisians increasingly enjoyed opera and ballet, a trend reflected in many Impressionist works. Yet, these seemingly opulent paintings hint at a darker reality. Degas’ ballet dancer paintings subtly suggest a connection between the ballerinas and sex work, with their audience cast as potential patrons.

A classroom setting with ballet dancers in white tutus and a man in the center, described as The Dance Class painting by Edgar Degas, displayed at The MET Museum

A classroom setting with ballet dancers in white tutus and a man in the center, described as The Dance Class painting by Edgar Degas, displayed at The MET Museum

The Rehearsal Rooms: More Than Just Dance in Ballet Dancer Paintings

In The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage (1874), Degas portrays dancers in practice, their movements fluid across the canvas. An instructor, presumably the choreographer, guides them at the center. To the side, two men observe the rehearsal from the wings. Their relaxed postures emphasize their position of power.

Ballet’s popularity waned in the 1870s, and many dancers, often from lower social classes, faced economic hardship. Sex work became a means of survival, sometimes encouraged by families struggling after the war. Ballet, ironically, offered a path to financial stability, which could intertwine with sex work. In The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage, the male observers could be interpreted as patrons watching the dancers, potentially to meet them later in the backstage rooms often used for practice. These spaces, depicted in ballet dancer paintings, become settings with dual meanings.

Ballet dancers on a stage rehearsing, with men watching from the side in the painting The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage by Edgar Degas, showcased at The MET Museum

Ballet dancers on a stage rehearsing, with men watching from the side in the painting The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage by Edgar Degas, showcased at The MET Museum

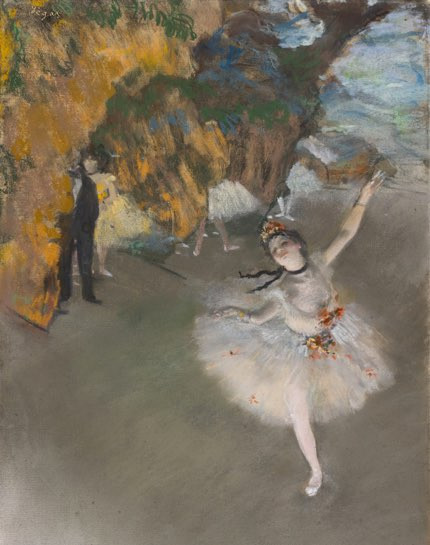

The Star Ballerina: Symbolism in Ballet Dancer Paintings like Ballet

Ballet (1876), sometimes referred to as The Star, is a particularly telling image in the context of the darker interpretations of Degas’ ballet dancer paintings. It features a lone ballerina center stage. A young dancer in a white tutu adorned with flowers dominates the foreground. While some believe she is Rosita Mauri, a Spanish dancer, her identity remains unconfirmed. The background is a wash of color depicting the set, curtains, and other dancers. A figure in a black tuxedo stands out against the colors. His face hidden, the figure’s presence feels imposing, even ominous.

Rumors circulated that ballerinas who entertained backstage patrons were favored with better roles. This perspective casts a shadow over paintings like Ballet, suggesting the “star” might have achieved her position through such arrangements. This adds a layer of complexity to how we view ballet dancer paintings from this period.

A single ballerina in a white tutu on stage with a dark figure in the background, captured in Edgar Degas' Ballet painting from 1876, displayed at Musée d’Orsay

A single ballerina in a white tutu on stage with a dark figure in the background, captured in Edgar Degas' Ballet painting from 1876, displayed at Musée d’Orsay

Voyeurism and Social Commentary in Degas’ Ballet Dancer Paintings

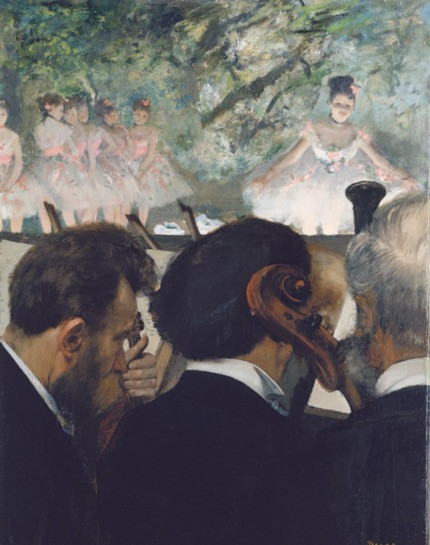

While the true stories behind each of Degas’ ballet dancer paintings remain speculative, the underlying atmosphere is palpable. In Orchestra Musicians (1872), the dancers are viewed from the orchestra pit’s perspective. The principal ballerina curtsies, while others gather behind her. Older musicians appear captivated by the stage, highlighting the voyeuristic element inherent in Degas’ work.

Men are often present on the periphery of his ballet dancer paintings, but in Orchestra Musicians, they are brought to the forefront. Despite the focus on the young dancers, the Palais Garnier was designed with the male patrons in mind. Backstage practice rooms were indeed intended for encounters with these patrons. The young dancers, often called “les petits rats” or little rats, were seen as commodities. Many were as young as 14. Orchestra Musicians starkly contrasts the older male audience and the young dancers, underscoring the challenging reality behind the Belle Époque’s glittering facade, as seen in ballet dancer paintings.

Musicians in an orchestra pit looking up at ballet dancers on stage, depicted in Edgar Degas' Orchestra Musicians painting from 1872, showcased at Städel Museum

Musicians in an orchestra pit looking up at ballet dancers on stage, depicted in Edgar Degas' Orchestra Musicians painting from 1872, showcased at Städel Museum

Beyond the Beauty: The Deeper Meaning of Ballet Dancer Paintings

Degas ballet dancer paintings, while undeniably beautiful, serve as a potent reminder that appearances can be deceiving. These relics of the Belle Époque encapsulate both beauty and a sense of underlying melancholy. They encourage us to look beyond the surface and consider the complex social realities of the time. Degas’ legacy lies in his ability to capture both the aesthetic grace of ballet and the subtle, often unsettling, stories hidden within his ballet dancer paintings.