Imagine stepping into a vibrant San Francisco nightclub in the 1940s. The air buzzes with excitement as a floorshow begins. A dancer in sequins executes a pas de bourrée, her partner captivating the audience with impressive splits. A bluesy voice fills the room with a classic tune. Then, a performer emerges, adorned with nothing but large feather fans, moving with languid grace. In this scene, what is the likelihood that these captivating dancers are Asian-American? For decades, San Francisco’s Chinatown nightclubs, most notably the Forbidden City, showcased that Chinese Americans were not confined to outdated stereotypes. They were stylish, talented entertainers who could command a stage, redefining perceptions and captivating predominantly white audiences with shows that sometimes incorporated elements of Asian Nude Dance within a broader context of burlesque and exoticism.

Forbidden City Nightclub Interior circa 1940s

Forbidden City Nightclub Interior circa 1940s

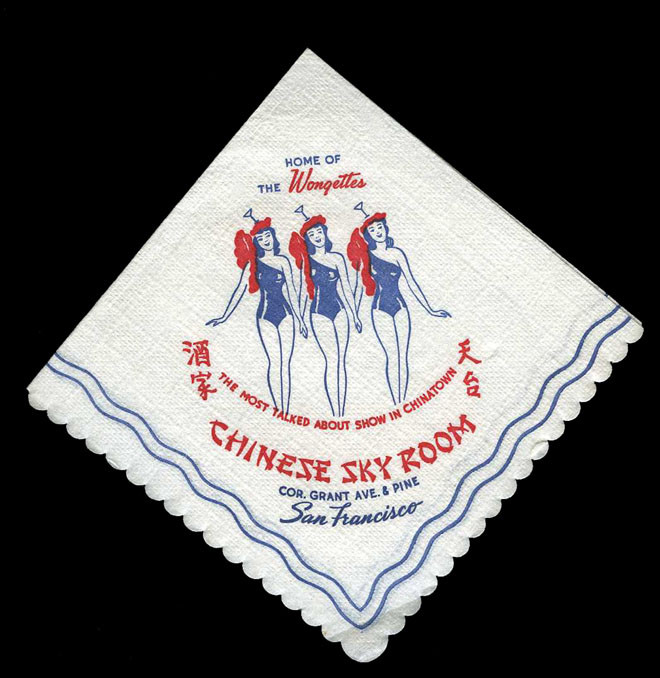

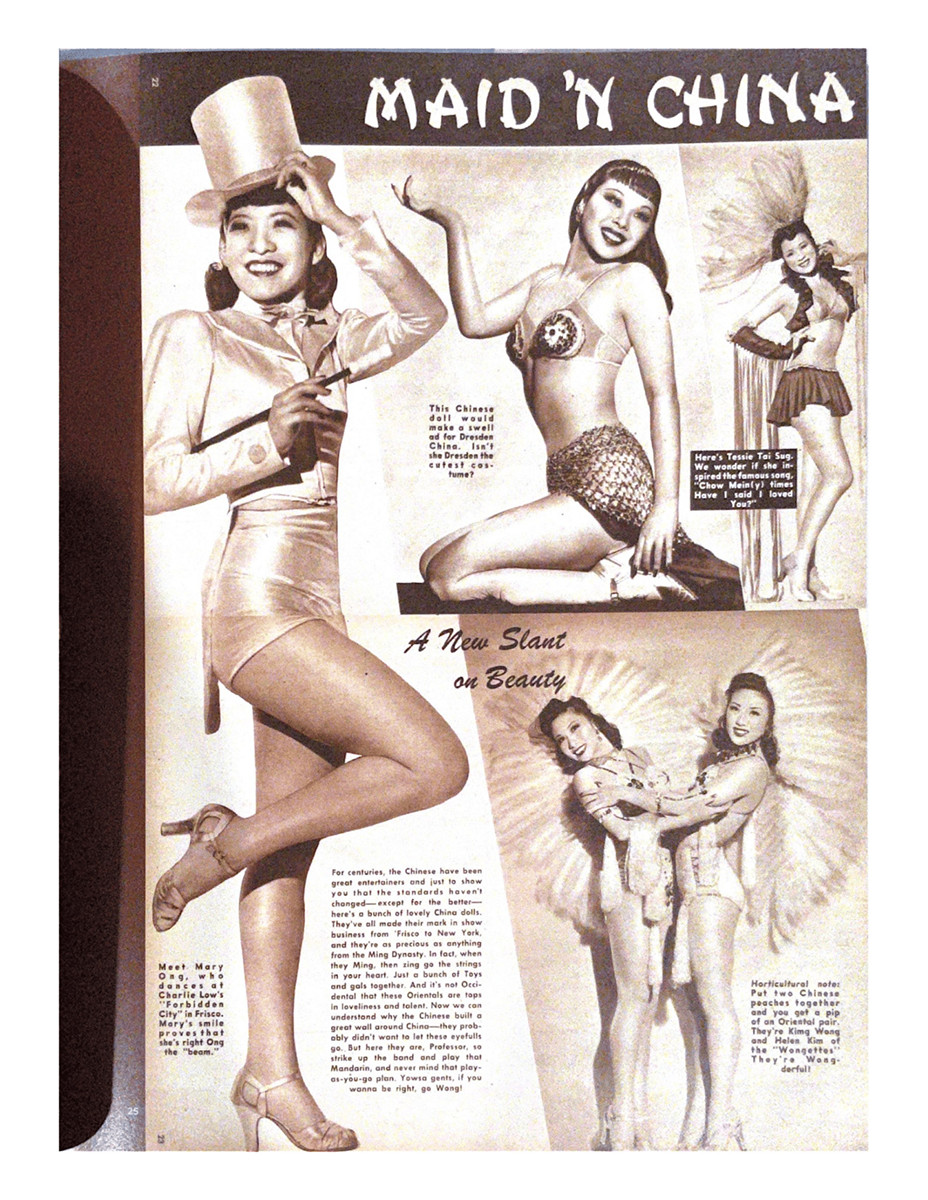

For nearly twenty years, the nightclubs of San Francisco’s Chinatown shattered racial barriers and outdated stereotypes. These venues demonstrated that Chinese-Americans were more than just laborers from a romanticized, distant land. They were sophisticated individuals who could dance, sing, and entertain, challenging societal expectations in glamorous nightclubs. During its peak, San Francisco boasted six nightclubs featuring all-Asian floorshows. These establishments, with names like The Dragon’s Lair, The Lion’s Den, Kubla Khan, The Chinese Sky Room, and Club Shanghai, deliberately played into the exoticism sought after by their largely white clientele. Among them, the Forbidden City rose to become the most renowned.

The visionary behind the Forbidden City was Charlie Low, who arrived in San Francisco from Nevada in 1922. During the Roaring Twenties, Low demonstrated his business acumen by persuading a brokerage firm to establish a Chinatown office under his management. Facing racial discrimination in 1927 when landlords refused to rent to his family, Low took a proactive step, assisting his mother in constructing the first modern apartment building in Chinatown. His passion for nightlife led him to the bar industry after Prohibition. In 1936, he inaugurated Chinese Village, Chinatown’s first cocktail bar, marking the beginning of his significant contribution to the entertainment scene.

The Forbidden City chorus girls as the “Devilettes”, L-R: Mary Ong, Lily Pon, Bertha Hing, Dottie Sun, Mary Mammon, ca 1940s.

The Forbidden City chorus girls as the “Devilettes”, L-R: Mary Ong, Lily Pon, Bertha Hing, Dottie Sun, Mary Mammon, ca 1940s.

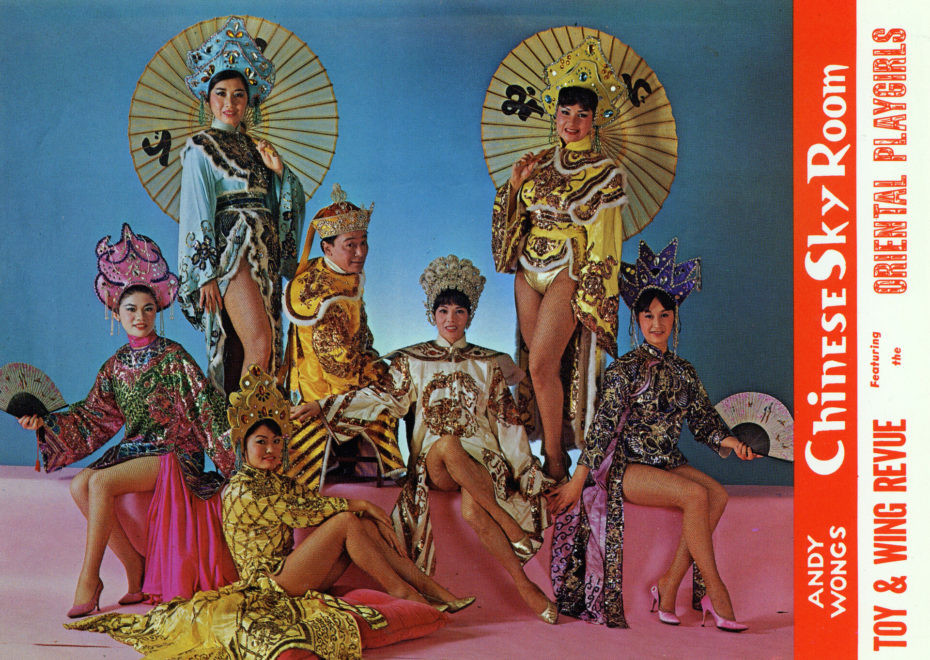

The subsequent year, Andy Wong, a trumpet player, opened the Chinese Sky Room just down Grant Street, establishing the first Chinese-American nightclub. Wong, who had previously played in funeral bands and a jazz sextet, the Chinatown Knights, envisioned a sophisticated nightclub reminiscent of those he had seen in movies. He wanted a place where his band could perform for elegant couples dancing the night away.

Andy Wong’s Chinese Sky Room, San Francisco Chinatown circa 1950

Andy Wong’s Chinese Sky Room, San Francisco Chinatown circa 1950

While Low’s cocktail bar was successful, he observed Wong’s venture and recognized a greater opportunity. Confident he could create an even more spectacular venue, especially with his talented wife, Li Tei Ming, a captivating torch singer, Low pursued his vision. He secured a location near Chinatown, decorated it with Chinese artifacts, and in 1938, launched the Forbidden City. Despite initial concerns about finding performers, Low recalled, “I thought I would have a lot of trouble in recruiting a good Chinese floorshow, but I was quite lucky.”

Mai Tai Sing and Wilbur Tai Sing, the smooth dancers of Forbidden City in 1942

Mai Tai Sing and Wilbur Tai Sing, the smooth dancers of Forbidden City in 1942

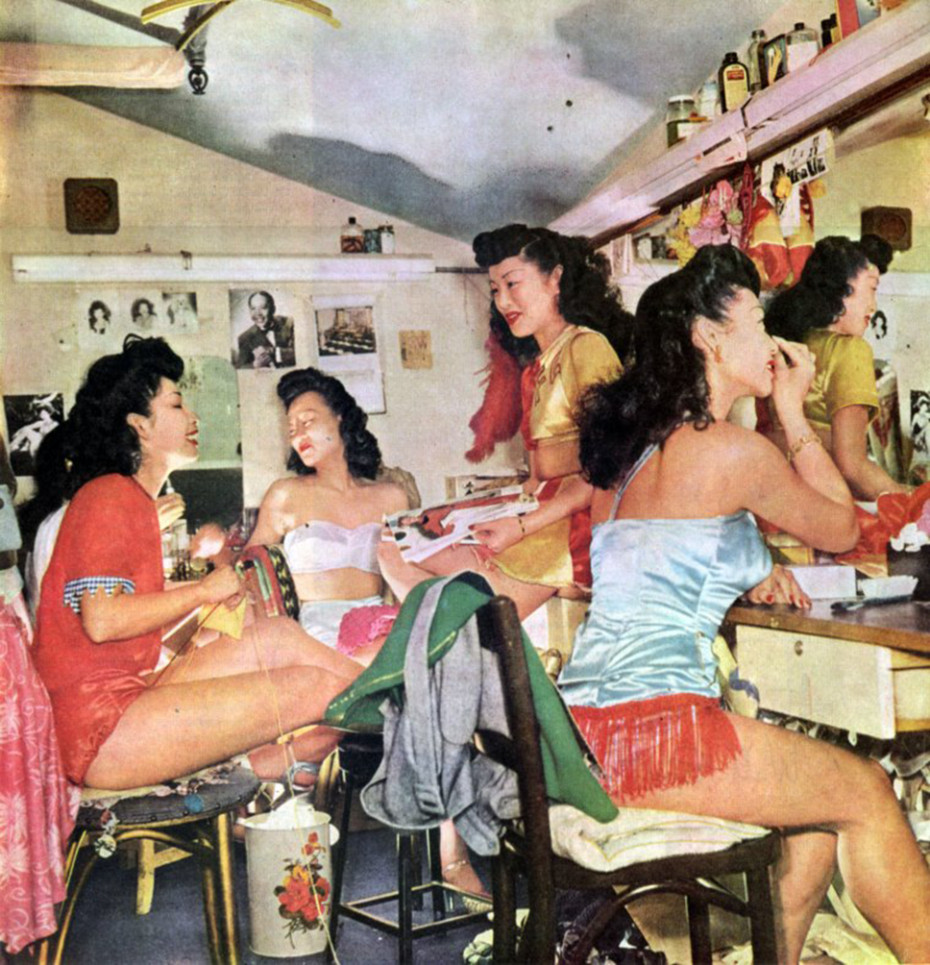

Low discovered a wealth of talent among young Asian-Americans in the city seeking opportunities. Born in America, they had grown up immersed in Hollywood musicals and jazz music. However, their immigrant parents, many of whom had overcome the barriers of the Chinese Exclusion Act, often held traditional views and were not always supportive of artistic pursuits. Consequently, many Forbidden City performers lacked formal training. By entering show business, these performers defied expectations from both their families and the predominantly white society. For the women, this career path also represented a challenge to patriarchal norms of modesty and decorum, particularly for those who engaged in more revealing forms of dance like burlesque.

Ellen Chinn, the headliner on opening night, was a teenage runaway from Monterey with a few years of dance experience. Many chorus girls, including Dottie Sun, Mary Mammon, and Mai Tai Sing, initially worked as cocktail waitresses while training under Forbidden City’s choreographer, Walton Biggerstaff. His studio became a crucial training ground for Chinatown nightclub talent.

Ellen Chinn was called the “Chinese Betty Grable.”

Ellen Chinn was called the “Chinese Betty Grable.”

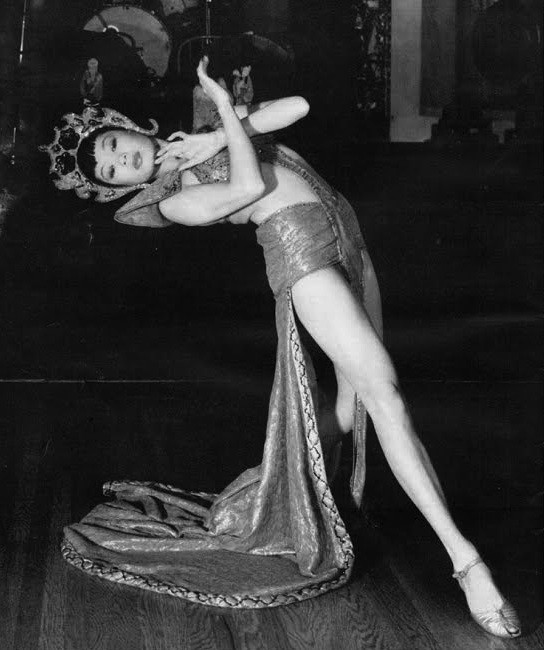

Jadin Wong, another opening night headliner, was an exception, possessing formal dance training. Driven by a passion for dance, she funded her own lessons from a young age. After a brief, unsuccessful attempt to find fame in Hollywood, Wong’s fortunes changed when she was spotted tap dancing on Hollywood Boulevard by director Norman Foster. This chance encounter led to lunch with Foster and an introduction to his wife, actress Claudette Colbert. This serendipitous meeting resulted in Wong’s appearance in Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation. Later, following a dance teacher to San Francisco, she found her place at the Forbidden City.

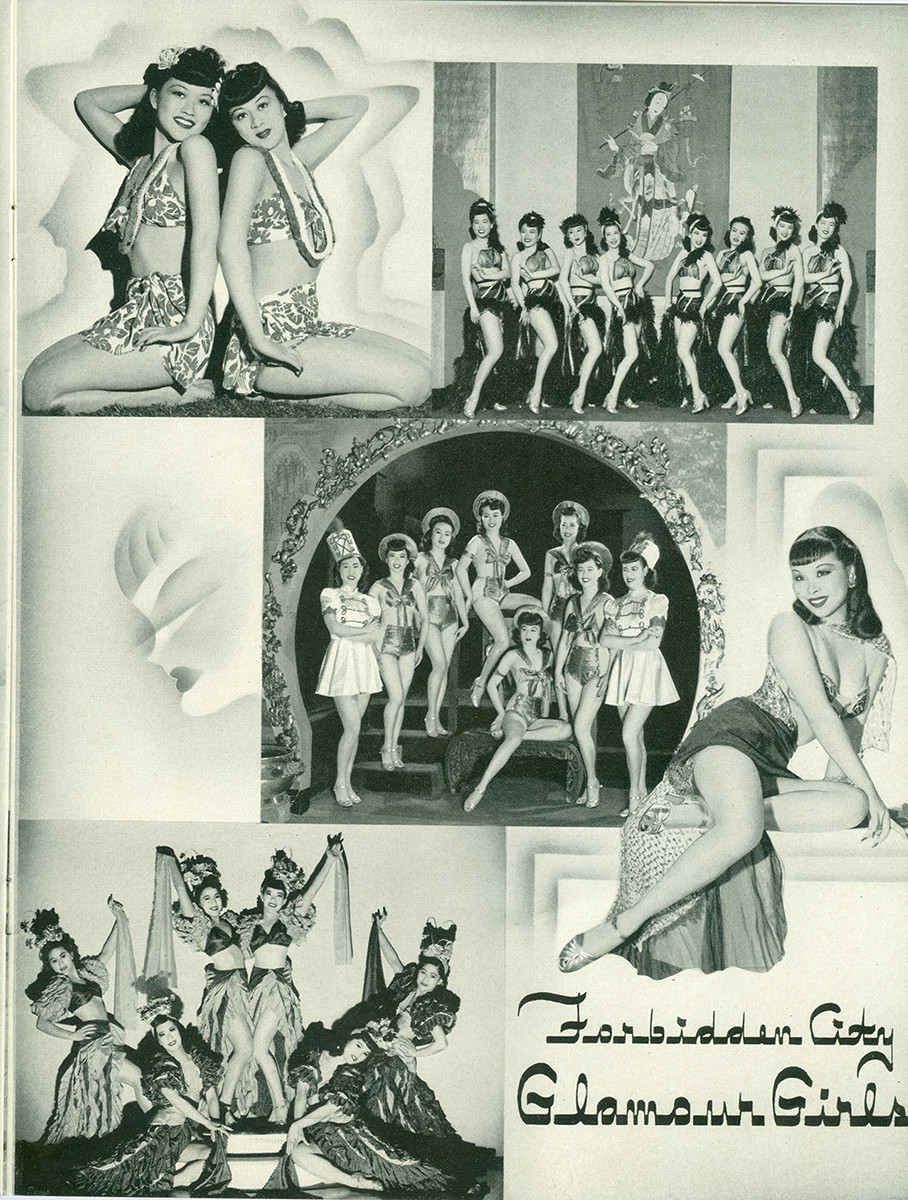

So many gorgeous Glamour Girls, from a Forbidden City souvenir program.

So many gorgeous Glamour Girls, from a Forbidden City souvenir program.

Larry Ching joined the merchant marines at 17 and honed his singing skills by listening to records onboard ships. After leaving the marines, he became a waiter at Charlie Low’s Chinese Village, refining his performance abilities while serving customers. His charm and smooth style earned him the moniker “the Chinese Frank Sinatra,” a label he disliked, preferring “Bing Crosby” or simply “Larry Ching.” Columnist Herb Caen famously quipped, “Frank Sinatra is really the Italian Larry Ching.”

Burlesque dancer Jadin Wong, 1940

Burlesque dancer Jadin Wong, 1940

Forbidden City offered patrons a choice of Chinese or American cuisine and an extensive cocktail menu. Each 45-minute show, performed three times nightly, featured singers, dancers, and variety acts. Shows often commenced with chorus girls in faux-Asian robes performing stylized bows to traditional music. They would then shed these robes to reveal dazzling, leg-baring outfits. From that point onward, the shows were distinctly American. While the initial exotic imagery served to attract the largely white audience, the Asian-American performers consciously moved beyond stereotypes. Singers performed contemporary hits, and dancers showcased jazz, rumba, and mambo styles. Burlesque acts, sometimes incorporating exotic costumes, featured the same bump-and-grind routines as their white and Black counterparts, demonstrating a fusion of styles and a rejection of simplistic Orientalist expectations.

Gorgeous Jadin Wong in 1941. (Museum of the Chinese in the Americas)

Gorgeous Jadin Wong in 1941. (Museum of the Chinese in the Americas)

Initially, business was slow, and Charlie Low faced financial challenges. Publicist Bill Steele suggested hiring a Chinese performer to emulate Sally Rand, whose nude fan dance was a sensation at the 1939 World’s Fair. Low encountered Noel Toy, a Chinese-American college student working at another risqué World’s Fair attraction, Candid Camera, where she posed nude for amateur photographs.

Babe magnet Larry Ching with Forbidden City ladies (l-r) Mai Tai Sing, Jade Ling, Diane Shinn & Betty Wong (the third Mrs. Charlie Low), early 1940s. (DeepFocus Productions Inc.)

Babe magnet Larry Ching with Forbidden City ladies (l-r) Mai Tai Sing, Jade Ling, Diane Shinn & Betty Wong (the third Mrs. Charlie Low), early 1940s. (DeepFocus Productions Inc.)

Toy accepted Low’s offer to perform at Forbidden City for $50 a week, using a giant balloon as her prop. Advertisements billed her as the “Chinese Sally Rand,” provocatively asking, “Is it true what they say about Chinese girls?” This strategy attracted white patrons intrigued by racialized and sexualized curiosity about Asian women. Noel Toy responded to the lurid questions with humor, famously quipping, “Oh sure, it’s just like eating corn on the cob!” effectively deflecting the racist undertones of the audience’s fascination with asian nude dance.

Noel Toy was dubbed the Chinese Sally Rand.

Noel Toy was dubbed the Chinese Sally Rand.

A Life Magazine photo essay on December 9, 1940, significantly boosted Forbidden City’s popularity. The four-page spread, titled Forbidden City “the No.1 all-Chinese night club in the U.S.,” featured captivating images of Jadin Wong in an exotic costume, Li Tei Ming singing, and the chorus line performing in rumba outfits. Life Magazine commented on the performers, stating, “Chinese girls have an extraordinary aptitude for Western dance forms. As singers, not many achieve success according to occidental standards. But slim of body, trim of leg, they dance to any tempo with a fragile charm distinctive to their race.” This national exposure, despite its mildly patronizing tone, dramatically increased the club’s visibility.

Noel Toy photographed by Murray Norman.

Noel Toy photographed by Murray Norman.

Following the Life Magazine feature, numerous publications highlighted Forbidden City, including Beauty Parade Magazine in 1943. Business tripled after the article and quadrupled after the U.S. entered World War II in 1941. San Francisco became a hub for servicemen and shipyard workers, all drawn to the exotic allure of Chinatown nightclubs. Celebrities like Errol Flynn, Ethel Waters, Ronald Reagan, Bing Crosby, Duke Ellington, and Frank Sinatra frequented these venues. Grey Line Tours regularly brought busloads of tourists to each show.

Jadin Wong at Forbidden City in the 1930s

Jadin Wong at Forbidden City in the 1930s

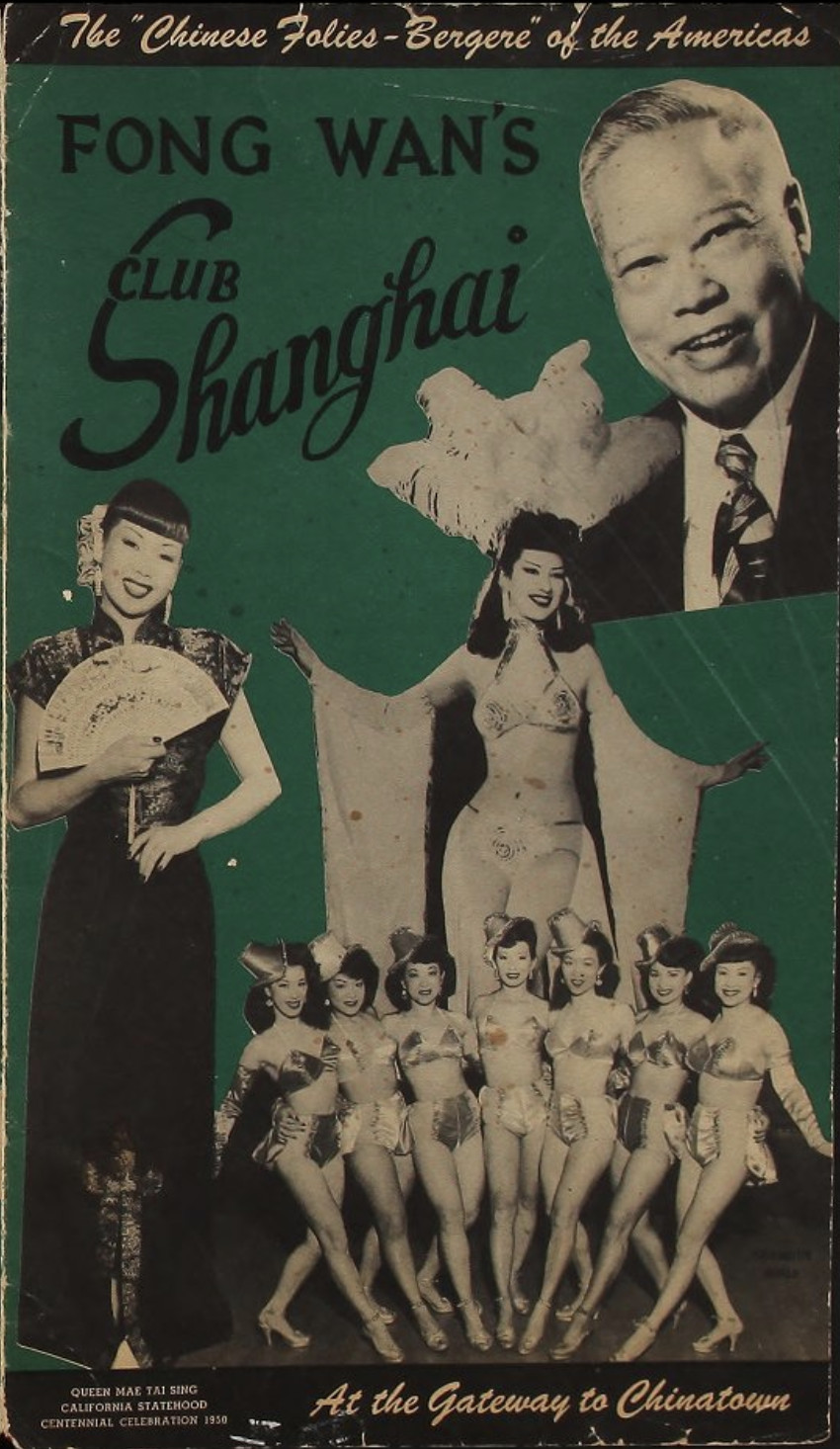

The success of Forbidden City spawned other Chinese-themed nightclubs, expanding opportunities for Asian-American entertainers. This period became known as the “chop suey circuit.” In New York City, the China Doll nightclub emerged, presenting revues with racially insensitive titles. Washington, D.C., also gained a similar club. In San Francisco, the number of such clubs grew to six, all Asian-owned and primarily located in Chinatown. Eddie Ponds opened the Dragon’s Lair and Kubla Khan, a lavish establishment where he was known for playing maracas with the Latin house band. When Fong Wan took over Club Shanghai in 1946, he and Charlie Low became rivals, culminating in Wan suing Low in 1949 for poaching an acrobat.

The photo of Forbidden City chorus girls in Life Magazine, 1940.

The photo of Forbidden City chorus girls in Life Magazine, 1940.

Asian-American performers were highly sought after during World War II, touring for organizations like the U.S.O., Stage Door Canteen, and the Red Cross. Jadin Wong reportedly even performed with Bob Hope in Europe. However, these performers faced segregation in the American South. Singer Frances Chun recounted an incident where she was confronted with “Black” and “White” signs in a restroom, unsure where she belonged. Dancer Jackie Mei Ling recalled being asked in a diner, “Are you people black?” highlighting the racial ambiguities and prejudices faced by Asian-American performers despite not experiencing the same level of hostility as Black performers.

Following Life Magazine, several papers featured Forbidden City including Beauty Parade Magazine, 1943.

Following Life Magazine, several papers featured Forbidden City including Beauty Parade Magazine, 1943.

Dorothy Toy and Paul Wing, a leading Asian-American dance duo, also faced challenges. Toy, who was Japanese but used a shorter surname, and Wing, faced scrutiny when Wing was mistakenly identified as Japanese. Amidst rising anti-Japanese sentiment, they relocated to Chicago to avoid potential internment. After Wing was drafted in 1943, Toy continued performing with her sister, though her parents were interned.

Jadin Wong with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall

Jadin Wong with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall

After the war, the novelty of Chinese-American nightclubs began to diminish. However, C.Y. Lee’s 1957 novel Flower Drum Song, set partly in the Forbidden City, kept the memory alive. The novel was adapted into a successful Broadway musical and a film in 1961.

club-shanghai-lg

club-shanghai-lg

Charlie Low retired in 1962, selling Forbidden City to Coby Yee, a headliner since the 1940s. However, business continued to decline. The rise of topless dancing in nearby North Beach in 1964 marked a turning point. With changing tastes and the proliferation of nude entertainment, variety clubs became less fashionable. Forbidden City finally closed its doors in 1970, marking the end of an era for asian nude dance and Asian-American nightclub entertainment in San Francisco.

Dorothy Toy and Paul Wing, the great dancing duo.

Dorothy Toy and Paul Wing, the great dancing duo.

While many performers from the Chinatown nightclub circuit transitioned into Hollywood, Broadway, and television, they often faced racial barriers that prevented them from achieving mainstream success. As the Vancouver Herald noted after seeing Jadin Wong perform, “If it were not for their race, they would undoubtedly be headliners in New York’s Rainbow Room or some other first-line cabaret.”

Jade Ling, who had an affair with Orson Welles before he met that Rita woman.

Jade Ling, who had an affair with Orson Welles before he met that Rita woman.

Many performers pursued different paths after the decline of the chop suey circuit. Larry Chin became a truck driver, and Noel Toy ventured into real estate. Some women retired to raise families. A few remained in entertainment, including ballroom dancer Mai Tai Sing, who owned a nightclub, and Jadin Wong, who became a talent manager for Asian-American artists, ensuring their continued presence in the entertainment industry.

Barbara Yung, one of the headlining burlesque performers in the 1940s. She performed at Club Shanghai and Kubla Khan.

Barbara Yung, one of the headlining burlesque performers in the 1940s. She performed at Club Shanghai and Kubla Khan.

Despite catering to a white audience seeking exotic entertainment, Chinatown nightclubs like Forbidden City offered a crucial platform for a generation of Asian-American entertainers. They challenged stereotypes, showcasing their talent and sophistication and proving themselves to be far more than simplistic “Oriental dolls” or menial laborers. Looking back, these glamorous figures in their gowns and tuxedos offer a poignant glimpse into a time when Asian-American performers shone brightly, even amidst societal prejudices and expectations of asian nude dance and exoticism.

Kubla Khan performers, 1950. Owner Eddie Pond is seated at right in the light-colored suit. The club closed not long after this photo.

Kubla Khan performers, 1950. Owner Eddie Pond is seated at right in the light-colored suit. The club closed not long after this photo.

coby-yee-late-1950s-930×704.jpeg

coby-yee-late-1950s-930×704.jpeg

Toy and Wings Oriental Playgirl Revue publicity for Chinese Skyroom Nightclub circa early 1960s

Toy and Wings Oriental Playgirl Revue publicity for Chinese Skyroom Nightclub circa early 1960s

coby-yee2-930×1163.jpeg

coby-yee2-930×1163.jpeg

backstage-at-forbidden-city-holiday-magazine-1948-930×965.png

backstage-at-forbidden-city-holiday-magazine-1948-930×965.png