Dance, as a living art form, constantly evolves, yet its essence remains timeless. The act of dancing, of embodying movement, ensures that dance stays alive, generation after generation. This is powerfully illustrated through the legacies of choreographic giants like Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown. Their influence continues to resonate, not just through archives and recordings, but vitally through the dancers who keep their spirit and techniques in motion.

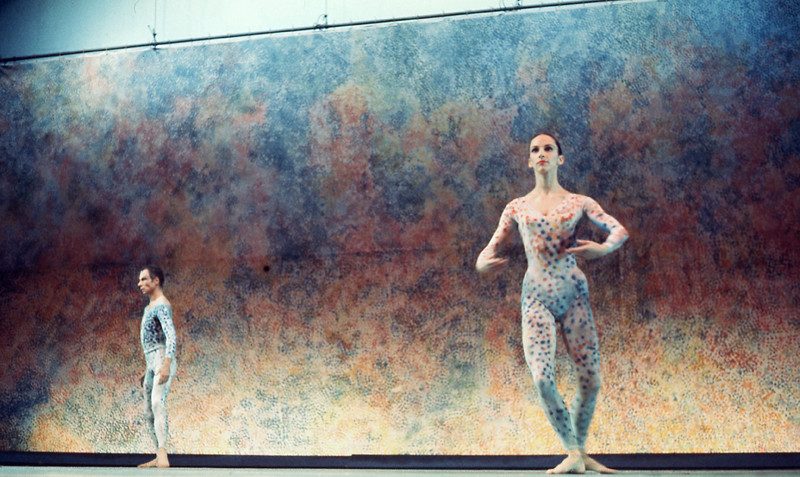

Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham performing <em>Summerspace</em> with backdrop and costumes by Robert Rauschenberg; Brooklyn Academy of Music, 1970. Photo: James Klosty.Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham in Summerspace dance performance, Brooklyn Academy of Music 1970, highlighting the innovative collaboration of dance and visual art.

Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham performing <em>Summerspace</em> with backdrop and costumes by Robert Rauschenberg; Brooklyn Academy of Music, 1970. Photo: James Klosty.Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham in Summerspace dance performance, Brooklyn Academy of Music 1970, highlighting the innovative collaboration of dance and visual art.

My own entry point into the world of Cunningham’s technique began unexpectedly, a testament to the enduring appeal of his work. Seeking a new physical and artistic challenge, I found myself one winter evening at the Merce Cunningham Studio. Despite the recent loss of its namesake, the studio pulsed with an energy that spoke to the ongoing vitality of his methods. Robert Swinston, my instructor, a direct link to Cunningham’s lineage, patiently introduced newcomers like myself to the foundational principles of the technique. The structured warm-ups, the intricate sequences built from simple movements, the emphasis on spinal articulation and dynamic legwork – it was a revelation. Cunningham himself famously said, “The only way to do it is to do it,” and indeed, immersion in the technique was the only way to grasp its profound logic and physical demands. This direct engagement, this physical learning, is a crucial part of how dance traditions are maintained and kept alive.

Merce Cunningham teaching class at Westbeth, New York 1971. Photo: James Klosty.Merce Cunningham teaching a dance class at Westbeth, New York in 1971, showcasing the direct transmission of dance knowledge to new generations.

Merce Cunningham teaching class at Westbeth, New York 1971. Photo: James Klosty.Merce Cunningham teaching a dance class at Westbeth, New York in 1971, showcasing the direct transmission of dance knowledge to new generations.

Even in the shadow of Cunningham’s passing and the impending closure of the school, there was a sense of burgeoning potential. For me, personally, Cunningham technique became a source of unexpected strength and artistic exploration. After years in other dance forms, this new approach opened up fresh pathways in my body and mind. It was a reminder that even amidst endings, new beginnings and new ways of staying alive in dance can emerge.

The news of Trisha Brown’s death in 2017 struck a similar chord. While personal acquaintance was absent, the deep connection to her artistic spirit was undeniable. Brown’s revolutionary ideas, her redefinition of dance itself, had permeated the dance world. Her fearless exploration of movement, whether it was dancers traversing building facades or the subtle accumulation of gestures, expanded the very definition of what dance could be. This boundary-pushing spirit is vital to the continuous evolution and staying alive of dance as an art form.

Brown granted permission to generations of artists to challenge conventions, to seek dance in unexpected places and forms. Her legacy isn’t just in her choreography but in the ripple effect of her innovative thinking. The outpouring of grief and tributes online, epitomized by Sarah A.O. Rosner’s poignant reflection on embodiment, highlighted the profound intimacy and lasting impact of dance. Embodiment, as Rosner articulated, is a deep intimacy, a way in which dance transcends the ephemeral and truly stays alive within the bodies of those it touches.

Concerns arose that Cunningham’s vast body of work might vanish with his death. However, recent performances by companies like the Lyon Opera Ballet and Compagnie CNDC-Angers, along with Walker Art Center’s extensive exhibition “Merce Cunningham: Common Time,” demonstrated the enduring presence of his creations. Under the direction of Robert Swinston, Compagnie CNDC-Angers brought Cunningham’s pieces to life, proving that his choreography could transcend time and continue to resonate with contemporary audiences. These revivals are crucial acts of keeping dance history alive and relevant.

Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Melissa Toogood and Dylan Crossman (left to right) performing Walker Cunningham Event. February 2017. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Photo: Gene Pittman.Dancers Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Melissa Toogood, and Dylan Crossman performing Walker Cunningham Event in Minneapolis, February 2017, exemplifying the dynamic energy of contemporary dance performance.

Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Melissa Toogood and Dylan Crossman (left to right) performing Walker Cunningham Event. February 2017. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Photo: Gene Pittman.Dancers Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Melissa Toogood, and Dylan Crossman performing Walker Cunningham Event in Minneapolis, February 2017, exemplifying the dynamic energy of contemporary dance performance.

The Walker Art Center’s exhibition, especially the “Events” curated by Andrea Weber, offered an intimate encounter with Cunningham’s world. These excerpts, performed in a gallery setting with live improvised music, revealed the raw vitality of his choreography. The brilliance of the dancers – Dylan Crossman, Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Melissa Toogood – was undeniable. They embodied Cunningham’s spirit, pushing the boundaries of movement with breathtaking precision and risk. Their performances weren’t mere replications; they were vibrant re-interpretations, breathing new life into Cunningham’s work and ensuring its continued relevance as a form of Staying Alive Dance.

The dancers’ ability to navigate the precarious edge of collapse and collision, their mastery of the technique allowing for transcendence, was captivating. A duet between Crossman and Scott exemplified this tension and control, highlighting the split-second timing and deep understanding inherent in Cunningham’s choreography. It’s through these dancers, through their dedication and skill, that Cunningham’s work truly stays alive and continues to inspire.

Yet, within the comprehensive “Common Time” exhibition, a subtle absence lingered: sustained recognition of the dancers themselves. While Cunningham and his collaborators were rightfully celebrated, the 163 dancers who embodied his vision over decades were acknowledged primarily through a collective list. Carolyn Brown, a pivotal figure in Cunningham’s company for two decades and author of a celebrated memoir, appeared in archival videos, but her profound contributions remained largely unexplored within the exhibition’s framework.

Alexandre Tondolo and Adrien Mornet of Compagnie CNDC-Angers in Merce CunninghamAlexandre Tondolo and Adrien Mornet of Compagnie CNDC-Angers performing Merce Cunningham’s How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run, showcasing the physical demands and precision of Cunningham technique.

Alexandre Tondolo and Adrien Mornet of Compagnie CNDC-Angers in Merce CunninghamAlexandre Tondolo and Adrien Mornet of Compagnie CNDC-Angers performing Merce Cunningham’s How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run, showcasing the physical demands and precision of Cunningham technique.

Wendy Perron, a former Trisha Brown dancer and dance writer, raised a pertinent question in 1976: “Is it possible that that old preconception of a dancer being a mere instrument of the creator is still around?” Decades later, this question remains relevant. When asked about Carolyn Brown’s contribution, Perron emphasized her “ongoingness,” her ability to convey “the idea that this dance just keeps going and going, and I, Carolyn, still have this floating tranquility above the whole thing.” This “ongoingness” is the essence of keeping dance alive.

While not co-choreographers in the traditional sense, Cunningham’s dancers, and indeed all dancers who interpret and perform choreography, are vital collaborators in the creative process. Their expertise, their individual qualities, and their unwavering dedication are what allow dance to unfold, evolve, and, most importantly, stay alive. There is no dance without dancers. It is through their bodies, their artistry, and their continued practice that dance breathes, persists, and remains a vibrant, living art form. The legacy of Cunningham and Brown, and indeed the future of dance, rests in the hands and feet of those who keep dancing.