It happened on a treadmill, of all places. There I was, powering through my workout, my usual running buddy to my left, and a stranger turned impromptu rival to my right. As our group of fifteen ramped up for a two-minute push, the instructor’s energy amplified, and the Rihanna remix of “We Found Love” seamlessly transitioned into something jarring: “Smooth Criminal.”

The opening beats hit, and a wave of unease washed over me. I half-expected the instructor to realize the playlist misstep, to rush back to the iPhone and skip to the next track. Surely, we weren’t actually going to run to Michael Jackson, were we?

But she didn’t. Not only did the song continue, but she started dancing along, completely immersed in the music. She was loving it.

Perhaps she was oblivious. Maybe Leaving Neverland hadn’t crossed her radar. Maybe she was simply unaware of the controversy. Or, the thought that truly unsettled me: maybe she knew, maybe she had seen it all, and simply didn’t care.

My memories of Michael Jackson are hazy, filtered through the lens of childhood. I faintly recall watching his 1993 Super Bowl Halftime Show. At seven years old, even then, something about the one-gloved figure on screen felt unsettling. This was pre-internet saturation, yet whispers and jokes circulated – “pedophile,” “creep,” “sick,” jokes about his supposed attraction to young boys.

And yet, his music was inescapable, and undeniably catchy. I even performed a tap routine to “They Don’t Really Care About Us.” And who of my generation didn’t find themselves swaying to a lyrical rendition of “Heal the World” at some point?

I remember in third or fourth grade, my tap and ballet combo class at Miss Pam’s dance studio was set to perform our recital to a Michael Jackson song. Then, abruptly, the music changed. We were given a different song. No explanation was offered to us kids, but I overheard hushed conversations among the moms in the lobby, murmuring about the accusations.

That was 1993.

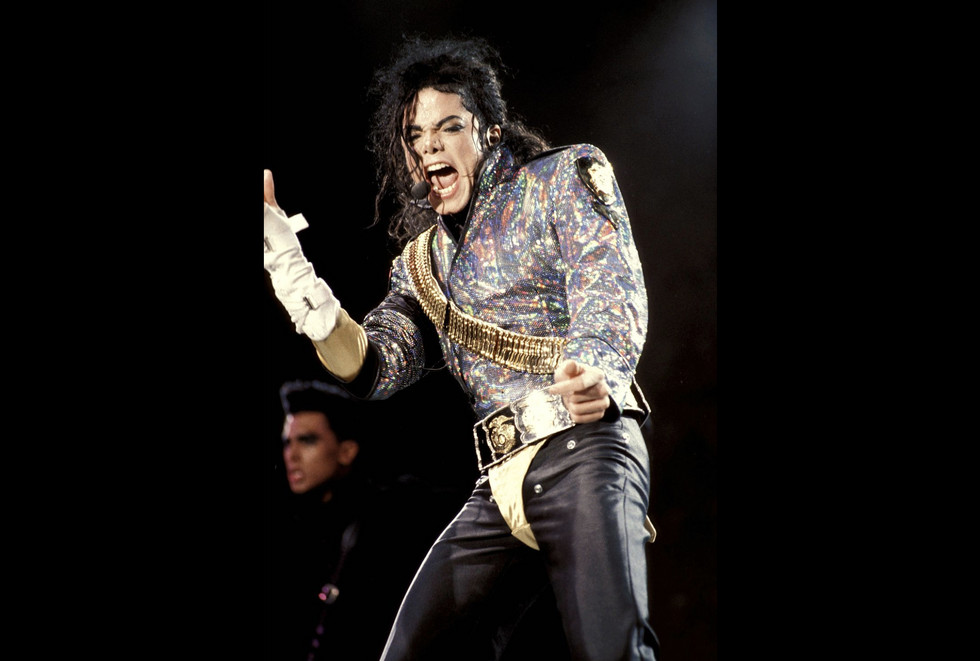

Michael Jackson, the King of Pop, performing his signature dance moves, a complex legacy in dance and music after Leaving Neverland documentary.

Michael Jackson, the King of Pop, performing his signature dance moves, a complex legacy in dance and music after Leaving Neverland documentary.

Despite the growing cloud of controversy, his music remained ubiquitous. “Man in the Mirror” became my anthem during dramatic teenage years, and “Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough” was my go-to pump-up track driving to early morning dance competitions. I loved the music, even as the man behind it made me uneasy.

But now, something has shifted. I can’t compartmentalize it anymore.

Last weekend, I dedicated five grueling hours to watching Leaving Neverland and Oprah’s subsequent interview with Wade Robson, James Safechuck, and director Dan Reed. Five hours of tears.

Tears streamed down my face watching Wade Robson, once a teenage dance idol of mine, recount his experiences of abuse and confusion. Tears of horror, of disbelief, of profound sadness. At sixteen, my dream was to work at Dance Spirit magazine specifically to write about Wade Robson. His March 2003 cover still graces my childhood bedroom wall. (Mom, please don’t ever take it down!)

Then came more tears, this time scrolling through Twitter, expecting to find a collective outpouring of shock and horror mirroring my own. Instead, I was met with a barrage of defenders. Wade and James were labeled liars, accused of exploiting Michael Jackson’s death for profit. Fans declared they would now listen to even more MJ than before, a defiant stance in the face of the allegations.

People can debate Leaving Neverland ad nauseam. But I believe Wade. I believe James. And I firmly believe that Michael Jackson’s music no longer belongs in fitness studios or dance classrooms. Jackson was undeniably a brilliant performer, an extraordinary entertainer. By those measures, he was world-class, unparalleled.

Throughout my career as a dance writer, I’ve had the privilege of interviewing countless dancers. While choreography trends, costume styles, and stage makeup evolve, one constant thread unites generations of dancers: Michael Jackson.

I’ve spoken to pre-teen dancers whose earliest dance memories involve mimicking the iconic moonwalk, a move Jackson popularized during his electrifying “Billie Jean” performance in 1983. (While not his invention, Jackson undeniably catapulted the moonwalk into mainstream consciousness, making it his signature.)

For dancers in their thirties and forties, Jackson’s entire discography formed the soundtrack to recitals, competitions, and high school dances.

Beyond just the music, Michael Jackson was a phenomenal dancer. The dance industry embraced him wholeheartedly. In mere seconds, he could seamlessly transition from that mesmerizing moonwalk into a dizzying 360-degree spin, culminating in a gravity-defying toe stand that seemed to hang in the air for an eternity. He was robotic yet fluid, meticulously rehearsed yet seemingly spontaneous, and utterly irresistible to imitate. And he wasn’t alone; Jackson often commanded entire dance ensembles, most famously in the groundbreaking “Thriller” video. As the undisputed King of Pop, his influence extended far beyond the music charts.

However, as a human being, the accusations against him are deeply disturbing and, for many, unforgivable. The fact that these allegations have persisted for decades is itself a chilling testament. Defending an adult man engaging in behind-closed-doors sleepovers with boys as young as seven is, to many, simply untenable.

This morning, a conversation with an online friend revealed a common sentiment. She acknowledged “hearing about all the Leaving Neverland stuff” but confessed she “can’t quit her MJ.” When I asked how that was possible, she explained that, for her, the man and the music exist in separate spheres. I vehemently disagree. For me, and increasingly for many others, the man is the music. The legacy of Michael Jackson And Dance is now inextricably intertwined with the serious allegations against him, forcing a critical reassessment of how we engage with his art.