Kanoe performing at House Without a Key

Kanoe performing at House Without a Key

For Kanoelehua Kaumeheiwa, her Hawaiian first name was once a source of childhood embarrassment. Growing up in multicultural Hawaii, surrounded by classmates with Hawaiian, Chinese, and Japanese surnames yet Westernized first names, Kanoe felt singled out. “Every time the teacher would call roll, she’d struggle over my name,” Kanoe recalls, reflecting on her school years. “Every grade, every class, even through high school, they struggled to pronounce my name. It got to the point where the whole class would anticipate the struggle and call out, ‘Oh, she’s here!’ when the teacher paused at the ‘K’s.”

This constant mispronunciation and attention made young Kanoe feel ashamed. “That always made me ashamed because it singled me out,” she explains. “I was shy, and this was in the 1960s, long before widespread awareness of ethnic pride. I even considered changing my name to something more common.” However, her father, deeply rooted in his Hawaiian heritage, vehemently opposed the idea. He instilled in her a vital lesson: “You need to be proud of who you are. There’s only one person with your name, so you have to be proud of it.” This paternal wisdom resonated as Kanoe matured. Entering the world of modeling and beauty pageants, she realized the uniqueness of her name was an asset. “He was right,” she acknowledges. “I was the only one with that name. So it was memorable, and eventually, I took pride in it.”

This pride radiates from Kanoe every time she graces the stage to perform hula, a dance deeply intertwined with Hawaiian identity and storytelling. Celebrated as the most photographed hula dancer globally, Kanoe Miller’s image has graced countless publications. Her mesmerizing performances are readily available online, captivating a devoted fan base who frequent House Without a Key, the elegant restaurant at Waikiki’s Halekulani hotel, where she has enchanted audiences for over four decades. Her journey, however, began not with a burning desire to dance, but with a mother’s gentle push.

“My mother forced me to take lessons,” Kanoe laughs, recalling her initial reluctance. “I wanted to take tap! But she insisted, ‘You have to go because it’s a summer special, and I can put you and your two sisters in there for $12 a month.’ This was back in 1966, or ’67.” Despite her initial resistance, Kanoe discovered a profound connection to dance. “I ended up liking it. I feel like I learned that I have the soul of a dancer because dancers love discipline, they love music, and they love to express themselves. Hula gave me all of that.” Hula, more than just steps, became a language, a way to express and embody the spirit of Hawaii, much like the significance held within a Hawaiian Dance Name itself, carrying stories and heritage.

Kanoe and her sisters in their younger years

Kanoe and her sisters in their younger years

As Kanoe’s modeling career took off in her teenage years, her hula instructor, the esteemed Ma‘iki Aiu Lake, noticed a shift in her student’s dedication. “I would come to class in a not correct attitude,” Kanoe admits. “I would arrive in makeup, lipstick, dressy go-go boots, fishnet stockings – it just wasn’t right.” Ma‘iki, a guardian of hula tradition, firmly corrected Kanoe’s approach and asked her to leave. The separation was temporary. When Kanoe set her sights on the Miss Hawaii pageant in 1973, she knew she needed a talent, and hula was her calling. “I had to go back and ask Ma‘iki if I could perform a specific hula written for her. That’s the proper protocol; you must ask permission.” Ma‘iki granted her request, and Kanoe’s victory in the Miss Hawaii competition propelled her onto a unique path. “Winning Miss Hawaii put me on a track of being in two worlds. I was modeling, deeply immersed in the fashion scene, but I was also dancing, with a foot firmly planted in the Hawaiian cultural scene. It was unusual. Most people chose one or the other.”

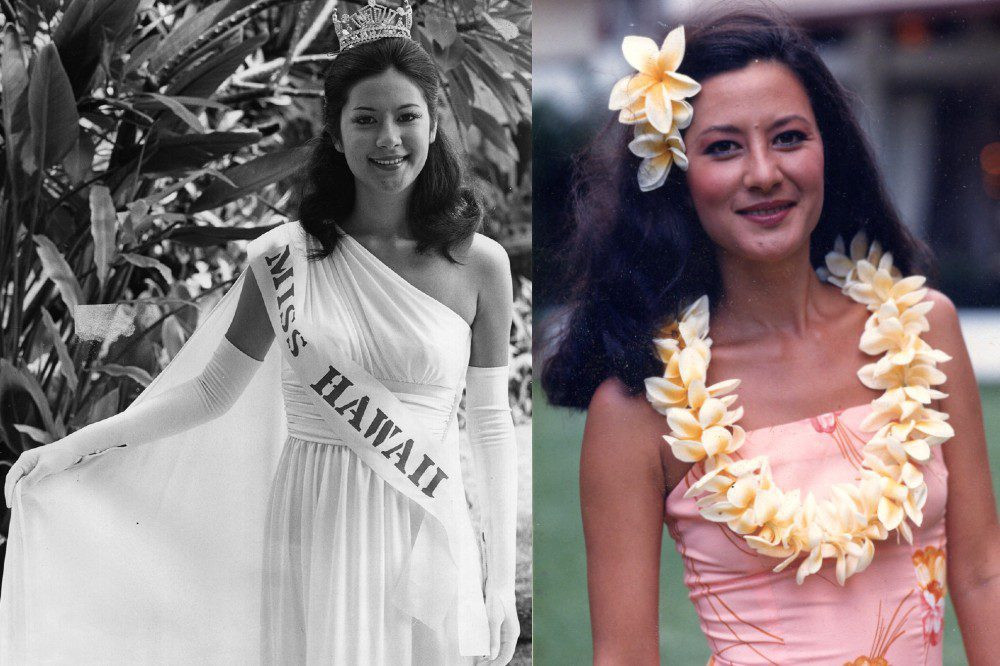

Kanoe Miller in 1973 as Miss Hawaii, and a decade later in 1983

Kanoe Miller in 1973 as Miss Hawaii, and a decade later in 1983

Kanoe’s journey coincided with the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s, a cultural resurgence reclaiming traditions suppressed for decades. Following the arrival of missionaries in the 1820s, hula, along with other cultural practices, was banned. King Kalakaua, the “Merrie Monarch,” who reigned from 1874 to 1891, revived Hawaiian dance, a legacy celebrated annually at the Merrie Monarch Festival. However, after his death and the annexation of Hawaii by the United States following the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, Hawaiian culture faced renewed repression. By the time Hawaii became a state in 1959, speaking Hawaiian in schools was discouraged, a stark contrast to the deep cultural meaning embedded in a Hawaiian dance name or any Hawaiian word.

“The Hawaiian language had almost died,” Kanoe reflects. “Hawaiian music had almost died. Walking through Waikiki, the traditional Hawaiian essence was largely absent. It wasn’t considered ‘in’ or ‘cool’.” The Hawaiian Renaissance aimed to reverse this cultural decline. “Everybody was reconnecting with their Hawaiian roots,” Kanoe explains. “People who might have previously hesitated to openly identify as Hawaiian or express their pride now embraced their heritage. Many even began using their Hawaiian middle names as their primary names.” Ironically, after Kanoe married John Miller, she sometimes faced questions about why she hadn’t retained her Hawaiian surname. “By then, I had been married for fifteen years!” she recalls of one such conversation. “And I replied, ‘You know what? I’m proud to be his wife, and I’m proud to be Miller. So, I’ll keep it as Miller.’”

Following her year as Miss Hawaii, hula steered Kanoe’s career in an unexpected direction. In 1976, she was asked to temporarily fill in for a dancer at House Without a Key. This temporary role evolved into a permanent fixture. While other dancers came and went, Kanoe remained a constant presence. “It was almost a throwaway job,” she describes. “Nobody really wanted it. It was very unglamorous. In the ’70s, the prominent shows were the large, elaborate Polynesian revues, offering abundant work for dancers skilled in Tahitian, Maori, and Samoan dances.” However, hula was Kanoe’s forte. In 1977, she was officially hired to perform one night a week at House Without a Key, a schedule that eventually expanded to six nights (currently, she dances every Saturday and every other Friday).

Kanoe Miller captivating the audience at House Without a Key

Kanoe Miller captivating the audience at House Without a Key

“I loved it because it just suited me,” she says, expressing her deep connection to the venue and the art form. She cherished dancing to the diverse musical selections of the three-piece bands: songs from the final years of the Hawaiian kingdom, the hapa haole tunes (Hawaiian songs with English lyrics) of the 1930s, reminiscent of “that Royal Hawaiian Hotel era – ‘Lovely Hula Hands,’ ‘Dancing Under the Stars,’ ‘I’ll Weave a Lei of Stars for You’ – that romantic hapa haole, so lyrical, beautiful, and descriptive of Hawaii’s natural beauty.” She also embraced contemporary songs, “very slack key, earthy, folksy music, the kind you’d hear on someone’s back porch.” Kanoe even admits a fondness for “cheesy stuff, like ‘Hawaiian Vamp’ – I love putting on that cellophane skirt and dancing to that!”

Yet, Kanoe emphasizes that hula transcends mere entertainment. It’s an art form, a powerful means of communication, and a vital way to preserve Hawaiian history. Before a written Hawaiian language existed, history was recorded through recitation and dance. In hula, every movement carries meaning. Those “lovely hula hands” are not just gestures; they are telling a story, conveying narratives as rich as any Hawaiian dance name passed down through generations. “Hula expresses who we are as a people, as a culture,” Kanoe articulates. “I received exceptional training from the best teacher, who was deeply invested in the culture and in expressing hula from the inside out. It’s not about superficial elements like hair and makeup or hand positioning. It’s about internalizing the essence of the dance. I meticulously study the lyrics, their meaning, the backstory, and the history of each song. Only then can I truly dance it. Without understanding the song’s narrative, you haven’t done your homework. That’s the mindset my teacher instilled in me.”

While Kanoe occasionally performed at private events, she found them less fulfilling. At these events, hula often became background entertainment. “It struck me, ‘Where are you truly appreciated, Kanoe?’ And the answer was, ‘At the Halekulani.’ So, I stopped taking those other gigs. At Halekulani, I feel like I’m doing something more meaningful than just performing at a corporate event. Over the years, it’s become like my home, an extension of my upbringing. I was raised in a very Hawaiian household; you enter, remove your shoes, leave anxieties outside, and then my father would bring out his ukulele, my brother his guitar, and we’d all start singing and playing. Our back porch became a gathering place for friends. When I’m on stage at Halekulani, I feel at home—the audience are my guests, not strangers.”

Another captivating shot of Kanoe Miller in performance at House Without a Key

Another captivating shot of Kanoe Miller in performance at House Without a Key

Kanoe expanded her reach with various projects, including producing the DVD Romantic Waikiki Hula with her husband. Promotional performances for the DVD led to larger-scale shows in Japan, where hula enjoys immense popularity. She also began teaching hula classes in Japan and Hawaii. Her digital magazine, Hula Studio, further broadened her influence. International performances became frequent. And through it all, her loyal audience at House Without a Key eagerly awaited her return. Life was vibrant and fulfilling.

Then, the pandemic struck.

The first sign of change came when Kanoe traveled to Japan in March 2020 to renew her artist visa in person. While there, she attempted to arrange a gathering with her students, but concerns over the burgeoning pandemic, amplified by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s call to avoid gatherings, deterred everyone. “I got my visa and immediately returned home. A week later, Halekulani’s general manager called, saying, ‘We’re closing this weekend, so you don’t need to come to work. We don’t know when we’ll reopen.’” Her scheduled April shows in Japan were canceled. Hawaii’s lockdown followed, halting her dance classes. Suddenly, all avenues of income vanished.

“March and April were filled with fear and desperation,” she confesses. “Then, one of my students suggested, ‘Why don’t you try teaching on Zoom?’ And I said, ‘What is that?’” Embracing the challenge, Kanoe and her husband delved into the world of online technology. Their living room transformed into a makeshift dance studio, equipped with mirrors, sound and lighting equipment, iPhones, cameras, and a 70-inch television—their first ever. “We had never owned a television; we always considered it an ugly piece of furniture and preferred reading or listening to music. Having a TV screen in our house felt like, ugh! But it was necessary.”

A closer portrait of Kanoe Miller, capturing her grace and spirit

A closer portrait of Kanoe Miller, capturing her grace and spirit

Social media advertising helped her quickly attract online students. However, teaching via Zoom presented a steep learning curve. “The very first class drove me crazy because I wasn’t accustomed to seeing everyone on screen moving in different directions. It looked like everyone was off-beat. I initially thought, ‘Wow, these people have no sense of rhythm!’ Every single person’s hand was in a different position. What is going on?” By the end of her first online class, despair overwhelmed her. “I thought, ‘Oh my God, this was a mistake. I can’t do this.’ I just curled up on the couch and cried. I really did! I thought, ‘We rearranged everything to do this, spent all this money, and it was a terrible mistake.’”

Realizing that the seemingly off-beat movements were due to online streaming delays, which could be as long as seven seconds, Kanoe started to adapt. Advice from friends experienced with online teaching and meetings proved invaluable. “They said, ‘You need to calm down and get used to it,’ and offered helpful suggestions.” Online teaching blossomed into an unexpected success. “It turned out to be wonderful because I could reach people all over the world. And during the pandemic, people needed activities while confined to their homes. It was perfect timing. It worked out well for me. I feel like I’m reaching an audience who always wanted to learn hula but couldn’t, and now they can. I believe this is the direction the world is heading. While I might lose some students when things fully reopen, I think I can continue to have online students.”

During the pandemic, Kanoe and her husband also created an online show, Hawaiian Rendezvous, inspired by the classic radio program Hawaii Calls. As restrictions eased in 2021, House Without a Key thankfully reopened last fall, bringing back the cherished live Hawaiian music.

However, since Kanoe’s early days performing in Waikiki hotels in the 1970s, Hawaiian music has been gradually disappearing from beachfront venues. “Yes, it has diminished,” she acknowledges. “Not due to a lack of talent, but a lack of space. The music and dance are no longer the focus; the emphasis is on drinking and socializing. It’s easier to place a musician or two in a corner, eliminating the need for a stage. Consequently, where does a hula dancer perform? Sadly, often right next to the tables, which is not elegant and doesn’t properly showcase our culture. That’s why I’m so grateful to be at the Halekulani. And next door at the Outrigger Reef hotel is the Kani Ka Pila Grille, which also features Hawaiian music, thankfully. Their style is more relaxed, backyard-style slack key, which I appreciate; ours is a bit more upscale and refined.”

Despite her dedication to promoting Hawaiian music and dance, Kanoe has faced criticism from some within the hula community for performing for tourists. “Isn’t that ironic?” she remarks. “I often ponder that. I used to receive a lot of negativity, and I still encounter it from certain individuals. But on the other hand, I am actively out there sharing what hula is—not to say others wouldn’t if they had the opportunity. Sadly, opportunities are scarce for them. That’s what needs to change.”

Kanoe Miller gracing the stage at the Hawaii Theatre

Kanoe Miller gracing the stage at the Hawaii Theatre

For Kanoe, hula has always been about opening hearts and minds to the richness of Hawaiian culture. “Watching me dance is just the tip of the iceberg,” she explains. “It’s a glimpse into our culture. For those wanting to delve deeper, there’s a vast ocean of knowledge to explore. But visitors here for a week don’t have that time. My hope is that by watching me dance, they grasp the spirit of this place, feeling, ‘Wow, this is truly special, evident in the music and the dance.’ That’s the feeling I want to evoke.”

She concludes, “When I perform hula, I want the audience to experience Hawaii—its spirit, natural beauty, history, and character. And I want them to feel aloha. To experience aloha through my dance, my interactions, or the warmth of my musicians engaging with them. I want people to feel aloha. That’s what truly matters to me. That’s the bottom line.”

Stay updated with Kanoe Miller’s journey on Facebook.