Contemporary Dance is a dynamic and ever-evolving art form that often sparks curiosity and questions, especially for those unfamiliar with its nuances. To delve deeper into this captivating genre, we interviewed Rachel Slater, one of the artistic directors of Muddy Feet Contemporary Dance based in Portland, Oregon. In this insightful conversation, Rachel unravels the complexities of contemporary dance, discussing its definition, the essential training for aspiring dancers, funding challenges, and the exciting directions in which this art form is heading.

Defining Contemporary Dance: Beyond Traditional Boundaries

When asked to define contemporary dance for someone without a dance background, Rachel acknowledges the inherent challenge. “It’s always a tricky question,” she admits, drawing on her experience teaching dance at a public high school with students of varying levels of dance education. She often describes it as “a dance form that prioritizes expression,” but quickly emphasizes the difficulty in pinning down a definitive visual style.

Contemporary dance, Rachel explains, is characterized by its boundless versatility. It can be performed to an incredibly diverse range of musical scores – from popular music and spoken word to classical compositions and even complete silence. Performance spaces are equally varied, encompassing traditional proscenium stages, raw warehouse settings, site-specific locations, and even film. Choreographically, contemporary dance embraces a wide spectrum of approaches. “There’s a lot of freedom and variety in the way choreography is generated, more than what is often found in a traditional or classical setting,” Rachel notes. The creative process often involves in-depth research and improvisation as key tools for generating movement material.

Ultimately, Rachel concludes, “contemporary dance can look like almost anything and is largely defined by its intention to be contemporary dance.” This inherent openness and focus on intentionality are central to understanding the genre’s fluid nature.

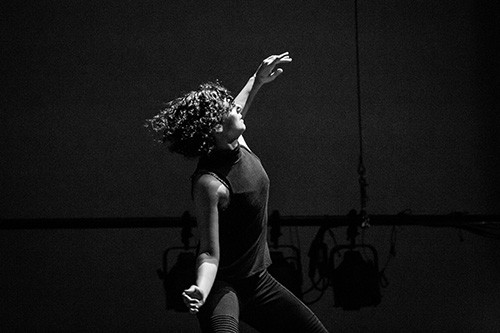

Rachel Slater in a dynamic contemporary dance pose.

Rachel Slater in a dynamic contemporary dance pose.

Photo by Meghann Gilligan showcasing Rachel Slater’s expressive movement in contemporary dance.

Essential Training for Contemporary Dancers: Embracing Versatility

For students aspiring to become contemporary dancers, Rachel stresses the paramount importance of versatility in training. She strongly recommends starting with “a strong background in ballet,” emphasizing its foundational value. “From there you have the ability to go anywhere,” she states. Ballet provides a robust technical base that dancers can either build upon or intentionally deviate from, but acquiring this foundation later in training is considerably more challenging.

Beyond ballet, Rachel advocates for “layering as many techniques as possible.” This includes exploring diverse styles such as Trisha Brown technique, Doug Varone technique, release technique, Gaga, Countertechnique, and Forsythe improvisation modalities. Exposure to a wide array of approaches allows dancers to become adaptable and responsive to different choreographic styles and creative processes.

Rachel highlights the contrasting demands dancers might encounter: “Some settings will have a more classical approach, asking you to make certain shapes and perform certain steps. Others are going to focus on concept and task.” Developing proficiency in multiple ways of working makes a dancer highly valuable to a wider range of choreographers. Furthermore, experiencing diverse dance environments helps dancers discover their own artistic interests and movement preferences, guiding their individual paths within contemporary dance. Even at a young age, considering desired dance paths is important for focused development, even though these aspirations may evolve over time.

Contemporary Dance: A Branch on the Modern Dance Tree

Rachel clarifies that contemporary dance isn’t simply any new dance form; it’s a distinct genre with historical roots. She positions it as “the most recent incarnation of modern dance.” Modern dance emerged in the early 20th century, around the 1930s, as a rebellion against the rigid structures of classical ballet. In turn, Rachel suggests, “contemporary dance is a rebellion against postmodern dance.”

Contemporary dance seeks to synthesize and expand upon the explorations of postmodern dance, which often emphasized conceptual and performance art elements. It poses key questions: “How can we build upon postmodern’s exploration of concept/performance art while still being expressive and technically daring? How can we still value the technique, training, and physicality of dance?” Contemporary dance grapples with maintaining technical rigor and expressive depth while embracing conceptual innovation. It also embodies “a constant exploration of what the human body can do,” continually pushing boundaries and questioning “Has everything been done?” in movement and expression.

Funding Contemporary Dance: Navigating a Challenging Landscape

The conversation shifts to the crucial topic of funding for contemporary dance, a persistent challenge in the arts. Rachel acknowledges the increasing prevalence of “freelance artists” in the dance world. While traditional company models still exist, offering dancers salaried positions with daily classes and rehearsals, “as funding continues to dry up, that model is less and less feasible.” Companies are also often constrained in their ability to take significant artistic or financial risks due to funding limitations.

When it comes to securing funding for artists who aim to push creative boundaries and take risks, Rachel is candid: “honestly, I don’t know.” Funding often becomes a patchwork process. Artists may seek foundational grants or cultivate donor bases to support specific productions, but many rely on “piece-meal their funding together.” Crucially, “Many dance artists get their funding by doing other work, which is often what engenders the ability to take risks and explore.” This necessity of supplementary income highlights the financial realities faced by many contemporary dancers.

Rachel points out geographical variations in funding landscapes. While acknowledging that funding for dance in Europe has also decreased in the past decade, she notes a significant difference: “my dance friends in Europe don’t hold other jobs, whereas most dancers in the United States have to hold an additional job.” Even dancers in salaried company positions in the US face job insecurity, as these roles are not lifelong.

Creative funding strategies are often essential, particularly for emerging artists. Portland, Oregon, where Rachel is based, illustrates a complex situation. The city’s growth is positive in that “there are more people wanting to make work,” but it also intensifies competition for limited resources: “the small amount of funding has more applicants. It’s tricky.”

Dancers in a contemporary piece, expressing emotion and physicality.

Dancers in a contemporary piece, expressing emotion and physicality.

Photo by Chris Peddecord capturing the intense physicality and emotional expression inherent in contemporary dance.

Rachel Slater’s Contribution: Choreography Rooted in Human Experience

Reflecting on her own contribution to contemporary dance, Rachel emphasizes her focus on “people.” Her choreographic process is characterized by valuing the individual perspectives of her dancers. “When I start to develop a new work, I’m interested in my dancers bringing their own perspectives, which I think is a distinguishing feature between classical and contemporary.” She actively seeks dancers who are not “blank slates waiting to be imprinted upon by a choreographer,” but rather collaborators with their own insights and experiences.

In her rehearsal process, dancers are often invited to “improvise, speak, write,” fostering a collaborative and deeply human environment. “As a choreographer, I’m interested in having real people in the room with me, not just someone who will nod their head and say, ‘Whatever you want.'” This ethos is reflected in her work, which aims to create a “conversation relatable to the audience.” Rachel believes that while “Dance can often be elitist and obscure,” grounding it in personal and relatable themes can bridge the gap between performers and viewers.

She cites her 2012 residency piece, Lorazepam, Sweaty Palms and the Shakes, inspired by her own experience with anxiety and panic attacks, as a prime example. The work resonated deeply with audiences, many of whom shared similar experiences and found it “relieving to see onstage.” This experience solidified Rachel’s commitment to “looking at people and seeing how dance relates, how it can be relevant to life.”

The Future Trajectory of Contemporary Dance: Technology and Divergence

Looking ahead, Rachel observes significant shifts in contemporary dance, particularly driven by “a huge impact from technology.” She notes the emergence of “long distance dance companies where the dancers Skyped and sent each other videos,” a concept virtually unheard of just two decades ago. Technology has transformed not only the creation process but also performance itself, with “so many ways video can intersect with dance, live or otherwise.”

Rachel also identifies a tension within the contemporary dance world, a divergence in artistic focus. One path emphasizes “concept-based work that walks the line between being theater, dance, and performance art,” often exploring “personal, political, or social commentary.” The other path prioritizes “technical physicality,” pushing the boundaries of athleticism and virtuosity in movement. Rachel is intrigued to see “which direction contemporary dance will go. Will it resolve itself or become two distinct paths? Or perhaps something in the middle will evolve.”

This divergence underscores the ongoing challenge of defining contemporary dance. Rachel returns to her initial point: “if you asked them to watch a heady performance art piece and then something akin to lyrical jazz, and called them both contemporary, they’d look at you like you’re crazy.” Yet, this breadth is the reality of the genre. Ultimately, she reiterates, “It boils down to the intention of the maker.”

Sustaining Contemporary Dance: The Financial Imperative

In her concluding thoughts, Rachel returns to the pressing issue of funding, emphasizing its enduring relevance. “The funding question is really relevant right now, though I suppose it always has been.” For Muddy Feet and countless other dance organizations, “we’re constantly renegotiating and trying to find new alternatives.” The fundamental need is “stability.” “If you have sustainability, you can focus on the art rather than funding the next show. It can be a draining question to readdress again and again.”

Rachel points to a historical imbalance in dance finances: “Dancers often don’t get paid.” The deep passion for the art form often leads dancers to “dance for free,” perpetuating a cycle where other collaborators, such as lighting designers and videographers, are often prioritized for payment over choreographers and dancers. Rachel expresses a desire to see “more agency for the dancer and choreographer,” advocating for fairer compensation and recognition. Achieving financial sustainability remains a “tough juggling act” for contemporary dance to ensure its continued vitality and growth.

A contemporary dancer in a moment of stillness and contemplation.

A contemporary dancer in a moment of stillness and contemplation.

Photo by Lindsay Hile capturing a moment of introspective stillness in contemporary dance.