Stepping back in time, there are aspects of the 1960s that evoke a sense of wistful longing, even for those who experienced later decades. While some elements, like the draft, are thankfully relics of the past, other facets of the era spark a feeling of having missed out on something truly special. For many, this sentiment is particularly strong when considering the vibrant dance culture that defined the decade.

Growing up in the 1970s, the dance scene felt disconnected and somewhat uninspired. The raw energy of punk, the polished moves of disco, and the regimented routines of aerobics, while popular, lacked the communal and expressive spirit that seemed to characterize dance in the preceding era. Punk often devolved into aggressive moshing, disco became synonymous with superficiality, and aerobics resembled little more than an intensified gym class. The dance floor, once a space for shared joy and liberation, appeared to morph into a stage for individual exhibitionism.

This shift made the idea of dancing less appealing. For someone already grappling with teenage angst, the introspective nature of 70s dance trends offered little escape. Staying on the sidelines felt like the more comfortable option. Even the once-ubiquitous square dancing seemed preferable to the prevailing trends of pogoing in spandex or mimicking the perceived materialism of disco culture.

The solace was found in music and the dream of classic cars. Yet, even this automotive fantasy was tinged with disappointment when reality hit – a 1978 Mustang, designed for a new era, couldn’t capture the raw power and iconic status of its 60s predecessors. It was during this period of reflection that the revelation struck: the decade of incredible music and cars had also possessed an equally captivating dance culture, a phenomenon missed entirely.

This realization began to dawn with the discovery of VHS compilations of Shindig!, a 1960s music variety show. Watching The Shangri-Las perform was a revelation. Their movements, a stark contrast to the polished choreography of groups like The Supremes or The Temptations, were equally captivating, if not more so in their raw, untamed energy. It was a style of movement that felt liberating, echoing the very spirit of the era’s music. Importantly, it looked accessible, as if anyone could join in. This proved to be true; unlike the meticulously choreographed Motown acts, The Shangri-Las devised their own moves, a fact revealed much later in an interview with lead singer Mary Weiss.

While becoming a dancer at that point felt like a ship sailed, the appeal of this 60s dance style was undeniable. It offered a sense of joyful participation absent in the dance trends of the 70s. This discovery fueled a quest to uncover more of this lost dance world, leading to the acquisition of Hullabaloo tapes and whispered-about Hollywood A Go-Go bootlegs – the holy grail of 60s dance television. Beyond the performances themselves, another element emerged as equally compelling: the dancers themselves.

These were not just local kids plucked from the audience, as seen on American Bandstand. The dancers on Shindig! and similar shows were demonstrably professional, selected through a more rigorous process. Some faces seemed familiar, recognizable from roles as dancers in “Elvis” and “Beach Party” movies. Toni Basil, for instance, appeared to be a ubiquitous presence in the “Beach Party” genre, both as a dancer and choreographer, later achieving pop stardom with her hit “Mickey” in 1981.

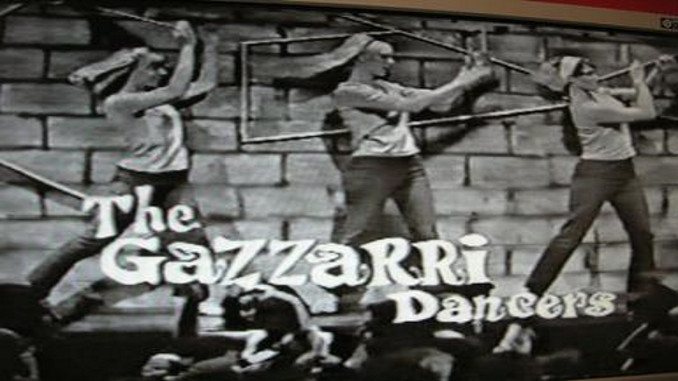

These dancers were largely provided by David Winters, a choreographer who would become a significant figure in 60s film and television, supplemented by talent from the vibrant Los Angeles nightclub scene. Those featured on Hollywood A Go-Go became collectively known as the Gazzari Dancers, named after the Gazzari’s club, a central hub for many of them. These weren’t just amateurs plucked from obscurity; they were skilled professionals, yet they embodied the same raw energy and spirit as the garage bands they often danced alongside. Even the average Hullabaloo dancer projected an image of the girl next door, albeit the most captivating girl on the block. They radiated not just enjoyment but a sense of genuine catharsis. It was a compelling and electrifying dynamic.

Gazzari Dancers in Hollywood A Go-Go

Gazzari Dancers in Hollywood A Go-Go

What emerged was a unique form of aristocracy – one open to anyone with talent and dedication, particularly those in Southern California, which, in 1960s America, held a certain cultural prominence. However, mere hard work wasn’t enough. Dancers like Teri Garr, who would later achieve mainstream fame in the 70s and 80s, weren’t cast in “Elvis” movies solely for their personality and work ethic. Discipline was a given, but the real criteria were more specific to the 60s ideal: tall, slender, blonde, and undeniably talented dancers. They embodied the fantasy ideal of a generation of young men glued to their television sets, while simultaneously possessing genuine talent and charisma that shone through the screen. This blend of aspirational image and relatable energy defined the 60s dancer.

The impact of these dancers, especially in the era of black and white television transitioning to color, and in homes where a 25-inch screen was a luxury, was profound. It created an illusion of inclusivity and possibility. In contrast to today’s performance landscape, where performers and audiences are acutely aware of the divide between them, the Gazzari Dancers, despite their select status, conveyed a spirit of both aspiration and belonging. They were undeniably talented and beautiful, yet they projected a welcoming energy that made the stage seem closer, more approachable, a place where anyone could potentially join in. If not a true meritocracy, it certainly felt like one within reach.

For those delving into bootleg tapes years later, the most significant impact of these dancers was the way they reshaped the music itself. Whether it was Motown, surf rock, garage bands, girl groups, folk rock, or even visiting British acts, the dancers on these shows created a sense of cohesion. Looking back, nothing captured the spirit of unity and togetherness quite like these dancers, not even the Jefferson Airplane song that proclaimed “we can be together.” Their ethos, unspoken yet palpable, was: “We’ll work hard, so we can show you how to let loose and have fun!”

The T.A.M.I. Show stands as the ultimate testament to this era – a cinematic masterpiece of rock and roll, arguably the greatest of its kind. Here, the dancers, Teri Garr among them, were integral to the show’s electrifying energy. Alongside iconic performers like James Brown, who reached unparalleled heights of showmanship, and legendary acts spanning genres, the dancers unified the diverse musical landscape. The T.A.M.I. Show captured a fleeting moment where Rock and Roll America seemed to coalesce into a unified vision – a vision that, sadly, has since faded.

The sheer talent assembled was staggering: The Godfather of Soul, The Rolling Stones, The Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Chuck Berry, Smokey Robinson, The Beach Boys, and the list goes on. For a brief, shining moment, there was a sense of shared understanding, a cohesive energy that pulsed through each performance, building upon the last. It’s hard to imagine recreating that collective spirit today.

It’s no coincidence that the dancers were at the heart of this phenomenon. They looked like they were having the time of their lives, genuinely wishing the audience could share in that joy. And in a way, through the television screen, they did.