This discourse is inspired by the Yizkor (Memorial) Sermon for the Seventh Day of Passover at Temple Beth El in Charlotte, North Carolina.

The voyage to liberation is not straightforward. Persevere… The journey through sorrow is not linear. Continue… It may be challenging. It may feel insurmountable. Keep moving forward.

From my childhood, I hold a distinct memory of attending Temple during the chaggim, the festivals: Pesach, Shavuot, and Sukkot. There we stood, my siblings and I, five children alongside our parents at Temple Israel in Westport, Connecticut, with only a few others present. Frankly, I struggled to grasp why my parents excused me from school for this.

Yet, here I am today, rearranging my schedule to be at the synagogue for a small, sacred gathering, just as Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy command.

There’s something about that early experience that draws me back to the shul on the chagim – as it draws you. It’s memory.

Yizkor – observed four times annually – near the culmination of our most sacred times, we pause to honor the memory of our ancestors – perhaps our parents, spouses, or siblings, and tragically, sometimes our children.

Four times a year – nearing the close of our holiest periods, we recite Yizkor: at Sukkot’s end on Shemini Atzeret; at the conclusion of the Ten Days of Repentance on Yom Kippur afternoon; today, at Passover’s end; and on Shavuot, marking the end of the seven weeks of the Omer count.

We pause. We contemplate. We remember. We grieve. We move forward. We keep going.

Why do we recite Yizkor during festivals? Tradition suggests it originates from Proverbs, stating, “Even in laughter the heart may ache, and rejoicing may end in grief.” (Proverbs 14:13).

However, I prefer a more balanced perspective, adding wisdom from Psalms: “Those who sow in tears will reap with songs of joy.” (Psalms 126:5-6).

Sorrow and joy, tears and laughter, are seen not as opposing forces but as intertwined aspects of grief and celebration, coexisting within us. As Ecclesiastes teaches, “a time to mourn and a time to dance.” Mourning and dancing reflect the dualities of our life’s path.

There were those hesitant to leave Egypt, clinging to the familiar, despite its oppression. The path to freedom, while desired, was also daunting. Similarly, the journey through grief is frightening. Our loved ones were our foundation: the people we sought advice from, the souls who brought us joy, the friends with whom we shared precious memories. They were our anchors of love and pride. How can we relive our greatest family moments, college milestones, life achievements, without them? They were integral to our memories. Yet, we keep going.

Today, we remember… those from our congregation who have passed — individuals who strengthened our physical structure, our spiritual foundation, and our community bonds. Today, we remember… those brutally murdered on October 7th — infants, youths, mothers, fathers, grandparents, peace seekers. Today, we remember… the soldiers who have fallen defending Israel. And we fervently pray for an end to this conflict, so that others are spared the mourning that we and so many others are experiencing. Our world is collectively grieving.

Judaism is fundamentally about memory. Passover is about memory. Yizkor is about memory. And all are directed towards a messianic purpose… a final state where God, with our partnership, will alleviate both individual and global sorrow. The tradition of opening the door for Elijah during the Seder embodies this aspiration for a better future and our commitment to help create it.

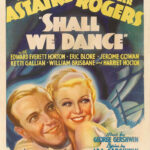

Today marks the anniversary of our passage through the sea to freedom, a moment of liberation we commemorate. We stood on the opposite shore, exhausted, elated, and traumatized. We persevered and found the strength to sing and celebrate. Moses and the Israelites sang a song of liberation. Miriam, prepared, had brought a timbrel, and she led the women in song and dance. This moment of singing and dancing after immense hardship is powerfully echoed in the sentiment of the “Dance Again Song.”

The Baal Shem Tov, the 18th-century founder of the Hasidic movement, taught that the journey through grief culminates in song. He posited three stages of mourning: tears, silence, and song. When we grieve someone deeply loved, we experience all three. First, we are overwhelmed by tears. As grief settles, we enter a period of silence. And ultimately, we find ourselves celebrating cherished memories through song. This progression towards song reflects the essence of the “dance again song” – a movement from despair to remembrance and celebration.

The Exodus narrative teaches us about resilience. It teaches us our responsibility to remember and to continue the legacy. It teaches us to celebrate – even amidst struggle. To sing. To dance. To live. To keep going, and in doing so, to find our own “dance again song.”

Midrash Shemot Beshallach (23:4) recounts that singing began with the Song at the Sea. God created Adam, but he did not sing. Isaac was spared from sacrifice, yet he did not sing. Jacob escaped danger and reconciled with Esau, but he remained silent in song. It was only the Israelites, in their exhaustion and exhilaration after crossing the sea, who sang. And God said, “Finally, the Israelites open their mouths with wisdom. I have been waiting for this.” This emphasizes the profound connection between overcoming adversity and the emergence of song, a connection central to understanding the power of a “dance again song.”

The last time we recited Yizkor as a global Reform Jewish community was on October 7th, at the close of Sukkot. On that day, over 3,000 predominantly young Israelis gathered for an all-night music festival, celebrating life and music. Yet, at the dawn of a new day, darkness descended upon our world. 364, mostly young people, including my own cousin, were murdered that day in a horrific act of violence.

In the aftermath, a powerful 150-day tribute emerged, poignantly named, “We will dance again.” This phrase, “We will dance again,” encapsulates the spirit of resilience, the refusal to let tragedy define us, and the commitment to reclaim joy and celebration even after profound loss. If the survivors and community of the Nova Festival massacre can commit to dancing again, to creating their own “dance again song,” then so can we all.

The destination of our journey to freedom is song. The destination of our journey through grief is song. The “dance again song” is not just a phrase; it’s a testament to the human spirit’s ability to heal and find joy even after unimaginable pain.

Yizkor – May God remember, and may we remember our loved ones who have passed. May we mourn. May we weep. May we keep going, transforming our grief into song and our tears into dancing. May we all find our “dance again song.”