The world of 1970s Hollywood was a fascinating, often turbulent place, especially within the walls of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). During the reign of James T. Aubrey Jr., known for his cost-cutting measures and sometimes erratic decisions, the studio experienced a period of both anxiety and, occasionally, unexpected outcomes. While Aubrey’s era is marked by cancelled projects and films perceived as creatively compromised, anecdotes from those who worked under him paint a vivid picture of his management style. One such story revolves around the film Cat Dancing, a movie that, against the odds, received a peculiar endorsement from Aubrey himself.

One former MGM employee recounts an experience that highlights Aubrey’s unpredictable nature and his impact on filmmaking. The narrative begins with a reflection on the quality of films during that period, contrasting them favorably against what the narrator considers “abysmal crud” of contemporary cinema. This sets the stage for a behind-the-scenes look at how studio politics and executive whims could influence the fate of a movie.

The anecdote reveals that Aubrey’s involvement often meant potential interference. Projects he disliked were sometimes sabotaged, while others were greenlit for reasons that seemed arbitrary. One example cited is Fred Zinnemann’s “Man’s Fate,” a project that was abruptly cancelled by Aubrey just before principal photography, allegedly for being too costly. However, the narrator suggests the real reason might have been the fear of it being too successful, a paradoxical approach to studio management. Zinnemann, despite this setback, went on to direct the critically and commercially acclaimed “The Day of the Jackal,” proving his talent regardless of studio interference.

Then comes the central story concerning Cat Dancing. Director Dick Sarafian, known for his work on Vanishing Point, was reportedly banned from the MGM lot during Aubrey’s oversight. When it came time for Aubrey to view Cat Dancing, he entered the studio theater and immediately questioned the film editor about removing a reel – a tactic Aubrey supposedly employed to intentionally ruin movies he disliked by creating audience confusion. This detail underscores Aubrey’s reputation for unconventional and often destructive meddling.

However, in a surprising turn, no reel was removed for the Cat Dancing screening. After watching the film, Aubrey’s reaction was unexpected. Instead of ordering further cuts or revisions, he simply declared, with a dismissive smile, to “ship the piece of s— just as is.” This quote, laced with irony and perhaps a hint of dark humor, suggests Aubrey’s low expectations for the film, yet also a strange form of acceptance, or perhaps indifference. He essentially greenlit its release by doing… nothing. This peculiar endorsement, or lack thereof, becomes the defining anecdote surrounding “The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing” – or, more accurately, the man who was indifferent enough to let it be released without further interference.

In stark contrast to his treatment of other projects, the narrator points out that David Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter was one film Aubrey left untouched. Lean, a director of considerable stature and influence, was not someone to be trifled with. The narrator speculates that Aubrey, perhaps recognizing the film’s potential for failure based on the script, simply opted to stay out of Lean’s way. This suggests a pragmatic, if cynical, side to Aubrey’s decision-making – he might interfere to sabotage films he perceived as potentially successful and therefore threatening, but would leave alone projects he deemed doomed from the start.

The anecdote about Ryan’s Daughter continues with a post-screening reaction. Despite Lean’s prestige and meticulous filmmaking, a color timer, immediately after a screening, bluntly declared it “the worst pile of crap I’ve ever seen.” The narrator elaborates on the film’s flaws: miscasting, with Sarah Miles and Robert Mitchum appearing disengaged, and Trevor Howard’s off-screen antics. However, Ryan’s Daughter was also visually stunning, boasting exceptional 65mm photography. The narrator describes the image quality as so pristine it felt like looking through a window at reality. Even the score, described as “dreadful” and sometimes resembling “circus music,” ironically seemed fitting for the film’s overall perceived absurdity.

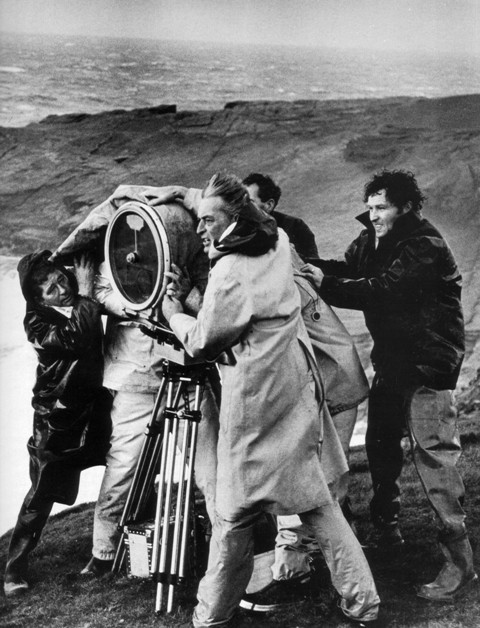

A specific technical innovation from Ryan’s Daughter is highlighted: the use of a ‘clear screen’ in front of the camera lens to film the powerful waves crashing on the Irish coast. This technology, originally designed for ship bridges to deflect sea spray, was adapted by Lean and cinematographer Freddie Young to maintain image clarity in challenging conditions. This detail showcases Lean’s commitment to visual excellence and his willingness to experiment with technology to achieve his artistic vision.

David Lean employs a clear screen mounted on a Super Panavision camera while filming the dramatic coastal scenes for 'Ryan's Daughter'. This innovative technique, originally designed for ships, allowed for capturing wave action without lens distortion from sea spray, showcasing the film's groundbreaking cinematography.

David Lean employs a clear screen mounted on a Super Panavision camera while filming the dramatic coastal scenes for 'Ryan's Daughter'. This innovative technique, originally designed for ships, allowed for capturing wave action without lens distortion from sea spray, showcasing the film's groundbreaking cinematography.

In conclusion, the stories surrounding James T. Aubrey Jr.’s tenure at MGM offer a glimpse into a chaotic and unpredictable era of Hollywood filmmaking. From sabotaged projects to bizarre endorsements, Aubrey’s methods were anything but conventional. The tale of Cat Dancing and the contrasting experience with Ryan’s Daughter illustrate the complex dynamics at play within the studio system and how individual personalities could shape, or in some cases, seemingly fail to shape, the movies that reached the silver screen. These anecdotes serve as valuable, if sometimes unsettling, insights into the behind-the-scenes realities of the film industry during a transformative period.