Dance Academy is an Australian television series that unfolds within the walls of a prestigious ballet school in Sydney. Designed for a young adult audience and international appeal, the show embraces familiar tropes: picturesque views of the Harbour Bridge and Opera House, the innocent protagonist, the quirky best friend, and the stereotypical mean girl. It also features the quintessential love triangle, the charming love interest, the brooding bad boy, and the endearing nerd.

The Dance Academy Season 2 Cast: A group shot featuring the attractive young dancers of Dance Academy. Five girls and four boys are present, all but one appearing to be white.

The Dance Academy Season 2 Cast: A group shot featuring the attractive young dancers of Dance Academy. Five girls and four boys are present, all but one appearing to be white.

What distinguishes Dance Academy, a compelling Dance Academy Show, is how its writers, including acclaimed YA authors like Melina Marchetta, skillfully play with these clichés. They delve deeper, allowing the ‘mean girl’ to confront her vulnerabilities, the ‘goofy best friend’ to acknowledge her self-defeating tendencies, and the ‘naive heroine’ to grapple with the complexities of reality.

My particular interest in Dance Academy lies in its nuanced portrayal of male characters. It’s important to remember that this is a show primarily targeted at young female viewers. While it’s crucial not to shift the focus solely to male perspectives in media aimed at women, the representation of men in teen fiction is consistently fascinating. Think of Edward Cullen as a blatant wish-fulfillment fantasy – a character so shallow he borders on parody. Dance Academy, however, while presenting familiar male archetypes, situates them within the intensely feminine environment of a ballet school. This setting allows the show to explore and often subvert gender stereotypes in intriguing, though sometimes problematic, ways.

The problematic aspect arises, especially in the initial half of the first season, from the show’s pronounced emphasis on the masculinity and heterosexuality of its male ballet students. The sole queer male character is a teacher, who is then replaced in the second season by a heterosexual man of similar age. While this plot development serves a narrative purpose—a student falsely accuses him of molestation, a storyline with its own set of complex issues rooted in the student’s background—it’s still disappointing to lose a gay male role model.

The male students often appear to be on the defensive regarding their masculinity. “They act like we’re not athletes,” complains Ethan when the dance academy is forced to share space with a football team. Christian faces criticism for lacking the core strength necessary for certain ballet movements. It’s worth noting that female characters also express concerns about strength and fitness, but for them, it’s often linked to anxieties about body weight – a realistic portrayal given the demanding world of ballet.

A scene from the “Best and Fairest” episode of Dance Academy, featuring football players humorously dressed in ballet attire confronting ballet dancers in street clothes. Patrick, the gay teacher from Dance Academy Season 1, is seen standing centrally.

However, the series subtly tracks the evolving attitudes of these young men towards masculinity. Early in the first season, Sammy, the kind, nerdy male friend, is informed of his weak ankles and advised to strengthen them by practicing in pointe shoes. Initially, this is treated as a joke, particularly for Sammy, who already feels his male identity is undermined after a rooming mix-up places him with a girl. Yet, after weeks of practice, the humor fades for everyone except outsiders unfamiliar with dance. The dancers recognize that pointe work has undeniably made Sammy a stronger, more proficient dancer.

The Nuances of Sammy Lieberman’s Journey in Dance Academy

Promotional image of Tom Green portraying Sammy in Dance Academy, showcasing his dance athleticism.

Sammy is a particularly compelling character within the Dance Academy series, and Tom Green’s performance is a standout element of the first two seasons. Samuel Lieberman grapples with the expectations of his ambitious father, who envisions a medical career for his son (“I know we don’t like to talk about it, but your grandfather was only a dermatologist.”). Coming from a conservative Jewish family with a close connection to his Yiddish-speaking grandfather, Sammy is acutely aware of the perceived disappointment in choosing dance over his academic potential.

He is also conscious of ballet’s stereotype as a “feminine” pursuit. His younger brother Ari, interested in gaming and martial arts, consistently reinforces this notion—sibling rivalry at its finest. This adds complexity to Sammy’s attempts to convince his father of the viability and rigor of a dance career, challenging the assumption that it’s an easy, “feminine” option.

Over two seasons of Dance Academy show, Sammy gradually reconciles with his non-alpha male identity, and his father eventually accepts his chosen path. But another layer of identity emerges: his sexuality.

The episode featuring the rugby players concludes with one of these traditionally masculine athletes asking Sammy out on a date. This moment is significant, considering football’s central role in Australian culture and the pervasive homophobia within its various codes. Australia has no openly gay professional football players. While efforts have been made to combat institutionalized racism in sports, homophobia and misogyny remain deeply ingrained. Depicting an openly gay footballer, even at a junior level, is a bold move for an Australian drama, especially one aimed at a young teenage audience.

Sammy is visibly surprised by the invitation, so much so that he awkwardly states he is “not available.” This subtly reveals his relationship with Abigail, which then joyously becomes public. Happiness ensues, and Sammy’s carefully chosen words, “I’m taken,” rather than a direct “I’m straight,” might go unnoticed if one isn’t paying close attention.

Therefore, it shouldn’t be a complete shock when Sammy later realizes, towards the end of the first season, that he experiences same-sex attraction and is drawn to his roommate and close friend, Christian. (It’s hardly surprising to be attracted to Christian; he possesses an undeniable magnetic charm.)

What follows is a coming-out narrative that is both familiar and refreshingly unconventional. Familiar because stories of “boy falls for boy and struggles with his sexuality” are common in contemporary media. Unconventional because Dance Academy explicitly acknowledges bisexuality as a valid identity.

“I have these feelings for Christian, and I don’t know if these feelings mean I’m gay,” Sammy articulates, using a metaphor to navigate the sensitive topic. Sammy fears he must choose between his perceived straight identity and his friendship with Christian.

This dilemma proves to be a false one. Sammy’s identity is far more multifaceted than just his sexuality, and while Christian doesn’t reciprocate romantic feelings, the honesty between them strengthens their bond.

In the second half of season two of the Dance Academy show, Sammy is tutored by Ollie, a third-year student. Their competitive dynamic evolves into a romantic relationship. Ollie, whose ego often overshadows his respect for boundaries, publicly outs Sammy by announcing their relationship to everyone.

Tara’s reaction to Sammy’s coming out is to enthusiastically hug him and exclaim, “I always wanted a gay friend!” This, while well-intentioned and adorable, is also portrayed as slightly problematic. Sammy responds awkwardly, “But… I’m not…”

Sammy spends the remainder of the episode grappling with two perceptions: firstly, that he is exclusively attracted to men, and secondly, that same-sex attraction equates to femininity. The first is imposed externally by his social circle. The second is internalized, reflecting societal norms Sammy has absorbed. He doesn’t personally view femininity negatively, but he is part of a culture that links male homosexuality or bisexuality with effeminacy. Having already challenged the stigma against male dancers, Sammy now confronts societal attempts to redefine his identity based on stereotypes.

Beyond this personal struggle, there’s his father to consider. Having just come to terms with Sammy’s dance career, how will this conservative, middle-class Jewish doctor react to his son having a boyfriend?

Sammy is portrayed as a genuinely good character who strives to do right. However, when he errs, he does so spectacularly. In a misguided attempt to manage the situation, he asks Abigail to pretend to be his girlfriend, inadvertently hurting both her and Ollie. Yet, when reconciliation occurs, and everyone is at peace, his father’s reaction is unexpectedly heartwarming. He witnesses Sammy and Ollie holding hands, smiles, introduces himself, and creates a genuinely sweet, affirming moment.

This positive scene makes Sammy’s subsequent death even more impactful and tragic.

The decision to kill off Sammy is deeply affecting. It’s a cliché to kill off gay or bisexual characters, a trope that arguably falls beneath the nuanced writing of Dance Academy show.

However, understanding the behind-the-scenes context offers some perspective. Tom Green was leaving the series (now known as Thom Green, he pursued roles in Halo: Forward Unto Dawn and NBC’s Camp, garnering critical acclaim). Sammy was integral to the narrative; simply writing him out would have been uncharacteristic. His core motivation was his passion for dance and his deep friendships. A sudden decision to transfer to another ballet school would have felt contrived and untrue to his established character.

What makes this loss somewhat bearable is Ollie’s continued presence as a main character. While replacing a bisexual character with a gay one is not ideal, it ensures the ensemble cast remains diverse in terms of sexuality.

Furthermore, even into the fourth episode of the third season, Sammy’s absence is deeply felt and significantly shapes the narrative. His friends grieve, reflect on his legacy, and gradually adjust to a world without him. He is gone but certainly not forgotten, leaving a lasting impact on the Dance Academy show.

Christian: The Archetypal Bad Boy of Dance Academy

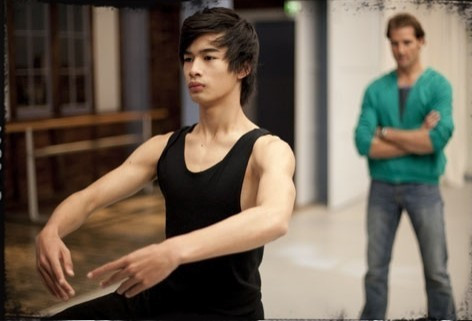

Promotional image featuring Jordan Rodrigues as Christian in Dance Academy, showcasing his dynamic dance ability.

Ah, Christian. Christian, Christian, Christian.

He embodies the Bad Boy Love Interest, the Troubled Young Man With A Past archetype. His mother is deceased; his father left early in his life. Partway through the first season of Dance Academy show, he is arrested for armed robbery. He is trouble, undeniably, but his exceptional dance talent earns him repeated second chances at the academy. He is also the captivating figure Tara struggles to move on from, even as she makes progress in season three.

He is undeniably a captivating character.

Confession time: Christian was the primary reason for initially tuning into Dance Academy. In a café, the series was playing silently on a TV screen. Attractive teens, dance sequences, Sydney scenery, and actor Jordan Rodrigues were all it took to pique interest.

Another confession: Christian’s appeal was partly due to his resemblance to Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender. Despite admiration for Dev Patel and his distinctive ears, the casting of The Last Airbender movie remains a sore point – a missed opportunity to cast Jordan Rodrigues as Zuko in a non-racist adaptation.

And yes, the main love interest in this dance academy show is a young Asian-Australian actor.

Australian television, in general, is overwhelmingly white. While some shows actively strive for diversity, these are often serious, adult dramas. Dance Academy, while predominantly white, is notable for featuring not one, but two prominent love interests who are men of color (Ollie will be discussed later).

(The racial homogeneity of the school likely mirrors the demographics of elite ballet academies. However, should strict accuracy always be prioritized in fiction? The first season included a Black extra, occasionally seen stretching in the background—once in pajamas and Ugg boots. Seasons two and three introduce a clique of junior dancers led by a brilliantly pretentious Asian dancer. However, these remain peripheral characters.)

(But back to Christian.)

Christian embodies a collection of tropes, not all positive. It’s questionable, for instance, that the sole Asian main cast member is the one entangled with the law. (In Australia, stereotypes link gang violence to Asian youth. In 2007, mentioning a move to Melbourne prompted a coworker to ask if I felt a lack of Vietnamese gangs in my life. Sharing reservations about Christian’s criminal past with an Australian unfamiliar with Dance Academy show led her to envision a character involved in organized crime. It’s important to remember, this is ABC3, not Underbelly.)

Christian also represents urban poverty within the series. Tara’s family faces financial strain, but they own a farm. The rest of the cast is firmly middle class, some even upper middle class. Christian, a scholarship student raised in Housing Commission Flats (public housing), is set apart. Class, arguably, shapes his character more profoundly than his race, reflecting Australia’s broader reluctance to openly discuss racial issues.

Christian acts as a bridge between social classes for his peers. He introduces Ethan to street dancers, rescuing Ethan’s hip hop choreography assignment from accusations of inauthenticity. (While appropriation remains a factor, informed appropriation is arguably better than uninformed appropriation. This mirrors the show itself – nuanced Australian accents often betray middle-class drama school backgrounds of actors portraying working-class characters.)

Later, when Kat decides to mentor a talented, underprivileged dancer, Christian cautions her that supporting a working-class kid is a long-term commitment, not a fleeting act of charity. Kat’s eventual understanding of her privilege becomes a significant part of her character arc, subtly handled, with Christian initiating this crucial awareness.

However, Christian’s background is often viewed as a liability by adults and authority figures. Teachers and administrators seem perplexed by his behavior. Why can’t he simply accept help, trust authority, and conform? This sentiment sometimes echoes within the fandom: why can’t he just get over his past?

The unspoken question lingers: why can’t he just be middle class?

(This brings to mind the Legend of Korra fandom’s reaction to Mako, another brooding love interest. Long before Mako’s romantic entanglements, fans criticized his supposed obsession with money—ignoring his background as a former street kid turned professional athlete in a system that exploits its “professionals.” While it was refreshing to see fandom critique a problematic male character rather than female ones, the tide shifted for Mako when discussions about his financial motivations emerged.)

(Classism within fandom is a fascinating dynamic, especially for those, like myself, relatively new to middle-class perspectives.)

This desire for Christian to fit a “nice, middle-class boy” mold becomes particularly evident when he is urged to articulate his feelings. The stoic, working-class male stereotype persists, but it clashes with the expectations of the school board and choreographers. Christian is repeatedly asked to verbally express his emotions, as if these authority figures seek to dissect his psyche. Christian, who communicates more through action and dance, understandably resists this pressure. The voyeuristic interest in his emotions makes him defensive, and rightfully so. “You’ve experienced more than your peers,” they seem to imply, “Entertain us with your pain, but also allow us to judge you.”

…In a Dance Academy vampire AU, the school board would undoubtedly be the bloodsuckers.

Christian practices ballet under the watchful eye of an older white male instructor in Dance Academy.

Christian practices ballet under the watchful eye of an older white male instructor in Dance Academy.

Season two of Dance Academy show marks Christian’s reunion with his estranged father. The absent Asian father figure is a less common trope than some, but Reed Senior is more chronically irresponsible than outright neglectful. He resides on the northern coast of New South Wales—an area perceived by Australians as a haven for hippie artists and meth users—and crafts surfboards.

The rebuilding of their relationship follows a familiar narrative arc, executed without significant novelty. Christian’s dad is a likeable character, but not particularly compelling (and the actor’s performance leans towards typical Australian soap opera acting). Interestingly, this quintessential “Aussie bloke” displays only mild interest and some paternal pride in his son’s ballet career. Anything more would have echoed Sammy’s storyline. It’s a subtle subversion of the rural Australian male stereotype. (In contrast, Christian finds common ground with Tara’s father through their shared interest in cars.)

Concluding Thoughts on Dance Academy (For Now)

One of Dance Academy’s strengths is its portrayal of adolescence as a period of boundary exploration—emotionally, professionally, and sexually. For the male characters, growing up within restrictive masculinity norms, this entails developing their identities as young men in a profession predominantly populated by women. This isn’t to diminish the female characters’ navigation of femininity and feminism, but these narratives are more frequently explored in media aimed at this demographic.

Dance Academy show is remarkable for addressing masculinity from multiple angles, largely avoiding misogynistic undertones. The storylines discussed complement, rather than overshadow, the narratives of the female characters. Within a series primarily aimed at a female audience, this inclusion is noteworthy. Balancing the portrayal of male struggles within patriarchy without eclipsing female experiences is a delicate act, and Dance Academy navigates this exceptionally well.

Coming soon: Analyses of Ethan, Ollie, and Ben in Dance Academy!