Sly & The Family Stone weren’t just a band; they were a cultural phenomenon, exploding onto the late 1960s music scene with a vibrant, groundbreaking sound that defied categorization. At the heart of their electrifying appeal was “Dance to the Music,” a track that wasn’t just a song, but an invitation – a call to unity and uninhibited joy. This wasn’t just music to listen to; it was music to move to, a revolutionary blend of funk, soul, and rock that broke down racial and musical barriers and cemented their place in music history. Let’s delve into the story of Sly & The Family Stone and how “Dance to the Music” became their explosive anthem and a timeless call to get on your feet.

A jukebox, with the words

A jukebox, with the words

From Rehearsal Rooms to Revolutionary Sounds: The Genesis of a Family Stone

To understand the impact of “Dance to the Music,” it’s crucial to understand the unique melting pot that was Sly & The Family Stone. Led by the visionary Sly Stone (born Sylvester Stewart), the band was intentionally diverse, a radical statement in a racially segregated America. Their formation wasn’t just about musical synergy; it was a deliberate act of social commentary. As Sly himself articulated, he questioned the very notion of black and white music, aiming to create a sound that transcended these artificial boundaries.

Before the Family Stone, the individual members were honing their skills in diverse musical landscapes. Jerry Martini, the saxophonist, experienced the almost-fame of George and Teddy and the Condors, a racially integrated band that tasted the edges of success, even encountering The Beatles. Greg Errico, the drummer, laid his foundation with Freddie Stone’s (Sly’s brother) earlier group, Freddie and the Stone Souls, and a soul outfit called the VIPs. Cynthia Robinson, the dynamic trumpeter, cut her teeth in a bar band backing blues and R&B legends.

However, none possessed Sly’s industry acumen and broad musical vision. Sly, a former radio DJ, was deeply aware of the racial divides in music and sought to shatter them. He envisioned a sound that was as innovative and melodic as The Beatles, as lyrically potent as Bob Dylan, and as intensely funky as James Brown. He wanted to bridge the gap between the burgeoning white counterculture in San Francisco and the rich traditions of Black music.

While precursors existed – bands like The Valentinos, The Chambers Brothers, and Love hinted at a similar fusion – none embraced the full spectrum of Sly’s vision. He aimed for a band that was not just racially integrated but also gender-inclusive, featuring female instrumentalists like Cynthia Robinson and later, his sister Rose Stone. He sought the vocal harmonies of groups like The 5th Dimension, fused with the raw energy of rock bands and the soulful punch of a horn section.

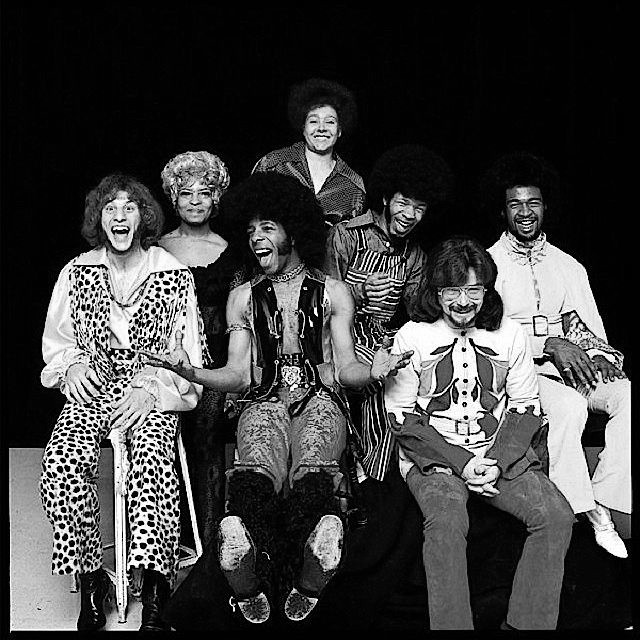

Sly and the Family Stone

Sly and the Family Stone

Early Gigs and Original Sparks: Forging a Unique Identity

In their early days, Sly & The Family Stone were a live band powerhouse, honing their craft in venues like the Winchester Cathedral. Their initial sets were built on crowd-pleasing covers, primarily soul and R&B hits, but even in these covers, the band’s unique identity began to emerge. Each member was given space to shine, reflecting Sly’s philosophy of shared spotlight and collective experience – “everyone gets a chance to sweat.”

Their live shows were meticulously structured to showcase individual talent while maintaining a seamless flow. Opening with Greg Errico’s drumbeat, band members would gradually join the stage, often weaving through the audience, creating an immersive and engaging experience. “The Riffs,” an instrumental piece showcasing their jazz chops, demonstrated their musical discipline. The music was continuous, songs flowing into each other, a non-stop party designed to captivate and energize.

It was at The Winchester Cathedral, under the brief management of Rich Romanello, that they began to inject original material into their sets. “I Ain’t Got Nobody (For Real)” was one of the first originals to surface, and even in its early form, it highlighted the collaborative nature of the band. Sly’s demo was a slow Latin jazz piece, but the band transformed it, injecting their collective energy and diverse musical backgrounds into its DNA, creating something distinctly Sly & The Family Stone.

The David Kapralik Connection and the Vegas Whirlwind

The band’s trajectory shifted when they caught the attention of David Kapralik, a record executive with a fascinatingly unconventional career. Kapralik, who had signed giants like Andy Williams and Barbra Streisand at Columbia Records, and even played a role in Bob Dylan’s early career, recognized Sly Stone’s unique brilliance. He was, by his own admission, captivated by Sly’s talent and vision.

Kapralik secured a residency for the band at the Pussycat A-Go-Go in Las Vegas, a crucial step in gaining wider exposure. Here, Sly & The Family Stone became the must-see act, drawing in other musicians and entertainers like James Brown, The 5th Dimension, and Bobby Darin. However, their Vegas stint was abruptly cut short due to the racially charged attitudes of the venue owner, highlighting the societal prejudices the band was challenging both musically and personally.

Despite the Vegas drama, this period was incredibly productive. Kapralik, now at Epic Records, a CBS subsidiary, signed Sly & The Family Stone. Every Monday, during their Vegas residency, the band would fly to Los Angeles and record, laying down the tracks for their debut album, A Whole New Thing.

“A Whole New Thing”: A Musician’s Album, A Slow Burn Start

A Whole New Thing, released in 1967, was indeed a new thing. It was a vibrant, experimental album that showcased the band’s raw talent and innovative approach. The opening track, “Underdog,” was a prime example, a re-worked song Sly had penned earlier. The album, infused with the spirit of summer 1967, even subtly nodded to The Beatles’ “All You Need is Love” with its intro.

While A Whole New Thing didn’t achieve mainstream commercial success, it became a sensation among musicians. Legends like Mose Allison and Tony Bennett were fans, and jazz producer Teo Macero lauded the album. George Clinton of The Parliaments (later Parliament-Funkadelic) was profoundly impacted by “Underdog,” recognizing new possibilities in music.

However, the album and its single, “Underdog,” underperformed commercially. Critics, like those at Rolling Stone, while acknowledging their novelty, found the album “interesting but not entirely effective,” missing the raw, live energy that defined their sound. Despite the critical misjudgment and commercial slow start, CBS remained convinced of Sly & The Family Stone’s potential.

New York and Rose’s Arrival: Completing the Classic Lineup

Following the Vegas experience and the lukewarm reception of their debut album, Sly & The Family Stone relocated to New York, securing a residency at the Electric Circus. This move coincided with a pivotal addition to the band: Rose Stone. Rose, Sly’s sister, joined on keyboards and vocals, solidifying the classic lineup and adding another layer of dynamism to their sound.

Rose’s arrival completed the family element of the band and further emphasized Sly’s vision of inclusivity. She was not just a vocalist but a multi-talented instrumentalist, embodying the band’s ethos of everyone contributing and “doing everything on stage.”

Despite their electrifying live shows and the completed classic lineup, record sales remained elusive. It was at this juncture that Clive Davis and David Kapralik had a crucial conversation with Sly. The message was clear: they needed a hit, something relatable, something danceable – a pop song, a single. They urged him to tap into his past as a producer of dance records and create something simpler, more accessible.

“Dance to the Music”: The Breakthrough Anthem is Born

Responding to the record label’s push for a hit, Sly Stone delivered “Dance to the Music.” This track, in some ways, represented a conscious shift towards commercial appeal. Jerry Martini, among others, felt it was a compromise of their artistic vision, a move towards a “formula style.” However, while commercially oriented, “Dance to the Music” was far from formulaic; it was a stroke of genius that synthesized their unique elements into a potent, irresistible package.

“Dance to the Music” drew inspiration from various sources. The line “Ride, Sally, ride” echoed “Mustang Sally,” while the song’s structure, introducing each instrument one by one, mirrored their live show introductions. King Curtis’ “Memphis Soul Stew,” which similarly built instrument by instrument, was another clear influence.

The song also incorporated a happy accident. During a rehearsal or performance, Sly forgot lyrics and filled in with “boom boom boom.” This improvisation became a signature element, incorporated into live shows and the recording, adding a playful, rhythmic hook.

Another accidental yet defining element was Jerry Martini’s clarinet. Arriving at an overdubbing session for which his sax parts were already recorded, Martini, to ensure he received his musician’s union fee, brought a clarinet instead of his heavier saxophone. While idly playing the clarinet, Sly recognized its unique sonic potential and incorporated it into “Dance to the Music,” making it perhaps the first soul hit to feature the clarinet as a lead instrument.

“Dance to the Music”: Chart-Topping Success and Cultural Impact

Released in the spring of 1968, “Dance to the Music” exploded onto the charts, becoming Sly & The Family Stone’s breakthrough hit, reaching the Top Ten. It was more than just a hit song; it was a cultural phenomenon, instantly recognizable and universally appealing.

The song’s impact resonated throughout the music world. Otis Williams of The Temptations, hearing “Dance to the Music” and other Sly tracks, urged Norman Whitfield to explore this new sound. Initially dismissive, Whitfield soon embraced the “psychedelic soul” sound pioneered by Sly, leading to hits like The Temptations’ “Cloud Nine,” which incorporated wah-wah guitar, call-and-response vocals, and even a nod to The 5th Dimension, echoing Sly’s own musical nods.

“Dance to the Music” became the cornerstone of their second album, also titled Dance to the Music. While the album itself didn’t achieve massive commercial success, peaking at number 142 on the pop charts despite the hit single, it solidified their sound and featured other dance-oriented tracks like “Ride the Rhythm” and the medley “Dance to the Medley.” It also included “Higher,” Sly’s re-imagining of “Advice,” the song he’d written for Billy Preston, further showcasing his songwriting evolution.

The song’s popularity even extended to a French-language novelty version, “Dance a La Musique,” released under the moniker The French Fries, highlighting its widespread appeal.

Fillmore East and a Shifting Dynamic: Sly Takes Center Stage

Following the success of “Dance to the Music,” Sly & The Family Stone’s live performances evolved. A pivotal moment was their appearance at the Fillmore East in May 1968, supporting The Jimi Hendrix Experience. According to David Kapralik, this gig marked a shift in the band’s dynamic. Previously a showcase of individual talents, Sly began to centralize the performance, diminishing individual solos and taking center stage. While not a complete erasure of individual contributions, it signaled a move from “Sly and THE FAMILY STONE” to “SLY and the Family Stone.”

Despite this shift, their Fillmore East performance was a triumph. Knowing they had to impress a Hendrix audience, they delivered a spectacular show. During one song, Sly, Freddie, and Larry famously jumped into the audience, passing the bass to Cynthia to maintain the rhythm, and led the crowd in a “Hambone” dance procession out into the street and back into the theater, a testament to their ability to connect with and energize an audience.

However, the Fillmore East gig also marked a darker turn. Jerry Martini recounts witnessing Freddie Stone’s first cocaine use that night. New York became a turning point, with cocaine becoming increasingly prevalent in the band’s life, particularly for Sly and Freddie.

The Shadow of Cocaine: A Turning Point

The rise of cocaine use within Sly & The Family Stone coincided with its growing popularity in the counterculture. While drugs like heroin, amphetamines, and LSD had been prevalent in earlier music scenes, cocaine began to take hold in the late 1960s and early 1970s, profoundly impacting music and culture. Sly Stone, ahead of the curve again, and several band members began experimenting with cocaine in 1967, becoming heavy users by 1968.

Cocaine’s effects, rooted in its disruption of dopamine reuptake in the brain, are powerful and insidious. Initially providing euphoria, increased energy, and suppressed appetite, it quickly leads to a cycle of dependence and negative consequences. Excessive dopamine can trigger psychosis, paranoia, hallucinations, and mood swings. The brain, seeking more dopamine, drives users to crave the drug, while long-term use rewires stress responses, making anxiety and stress more intense when not using.

For Sly & The Family Stone, cocaine’s influence became increasingly apparent. While “Dance to the Music” had propelled them to fame, the follow-up single, “Life,” failed to chart, though its B-side, “M’Lady,” had minor success in the UK. A UK tour to promote these singles was marred by Larry Graham’s arrest for marijuana possession and equipment issues orchestrated by promoter Don Arden, known for his aggressive and exploitative tactics. The band, faced with substandard equipment, refused to perform, choosing integrity over a compromised show, even in the face of Arden’s threats.

“Life” and “Stand!”: Navigating Success and Shifting Sands

Their third album, Life, released less than a year after their debut, marked a deliberate shift away from the pure party vibe of Dance to the Music and towards more experimental and socially conscious themes, aligning with the evolving hippie rock scene. Tracks like “Plastic Jim” referenced The Beatles and The Mothers of Invention, showcasing their broadening musical palette. While geared towards the white rock market, Life failed to achieve commercial success, threatening to pigeonhole them as a one-hit wonder.

However, the enduring popularity of “Dance to the Music” led to a pivotal appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Their performance included a medley of “Dance to the Music,” “Music Lover,” and “I Want to Take You Higher,” showcasing their dynamic stage presence. Notably, they debuted a snippet of a new song during this performance – “Everyday People.”

“Everyday People” was meticulously crafted for mass appeal. Built around Larry Graham’s iconic slap bass line, a simple two-chord structure, and a “na-na-na-na-na” melody, it was instantly catchy and universally relatable. The song’s hooks were abundant – the horn line, the chorus, and the counter-vocal “We got to live together.”

Released in late 1968, “Everyday People” became a massive hit, reaching number one and selling a million copies. Billboard ranked it as the fifth biggest hit of 1969, fulfilling Sly’s ambition for it to become a standard. Covered by a diverse range of artists, from The Staple Singers to Dolly Parton and Peggy Lee, “Everyday People” transcended genre and generation.

The song’s message of unity and tolerance, particularly its focus on racial harmony, resonated deeply in the late 1960s. In a time of social upheaval and the Civil Rights movement, “Everyday People” offered an optimistic vision of a future where differences were celebrated and everyone had equal opportunity. Sly’s philosophy at the time, emphasizing individual responsibility and universal fairness, was encapsulated in the song’s message.

Following “Everyday People,” their next single, “Stand!,” the title track of their fourth album, also achieved significant success, reaching number 22. “Stand!” marked a shift in Sly’s studio approach. Dissatisfied with initial reactions to the track, he brought in session musicians to add a new tag, which became a signature element of the song. This highlighted Sly’s increasing control in the studio and his willingness to use session musicians when needed.

The B-side of “Stand!,” a re-worked version of “Higher” titled “I Want to Take You Higher,” became another hit, even as a B-side, further demonstrating their creative peak. “I Want to Take You Higher” also became widely covered, notably by Ike and Tina Turner.

Stand!, released in 1969, was their fourth album in just eighteen months, a remarkable output. Despite the rapid pace, the album was a creative and commercial triumph. Five of its seven tracks would later be included on their Greatest Hits compilation, solidifying its status as a classic. Tracks like “Don’t Call Me N____r, Whitey” revealed a more confrontational edge, addressing racial tensions with directness.

Festival Summer of ’69 and Woodstock’s Peak

The summer of 1969 was a whirlwind of festivals for Sly & The Family Stone, showcasing their broad appeal across diverse audiences. From the Toronto Pop Festival to the Harlem Cultural Festival (the “Black Woodstock”), they shared stages with artists ranging from Chuck Berry to the Velvet Underground.

Their performance at the Harlem Cultural Festival was particularly significant. At a time of heightened racial tensions in New York, the festival, aimed at community cohesion, relied on the Black Panthers for security, highlighting the social context of their music and message.

At the Newport Jazz Festival, their performance was blamed for inciting a riot, as crowds broke down fences to enter, drawn by their electrifying energy. Police were called in to manage the out-of-control crowd, underscoring the band’s powerful impact on audiences.

In the midst of festival appearances, they also played the Apollo Theater in Harlem, a crucial venue for Black artists. Initially met with skepticism due to the band’s racial makeup, Sly addressed the audience directly, emphasizing their commitment to integration both on and off stage, ultimately winning over the crowd.

During this period, they released “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” another massive hit, reaching number two and becoming a summer anthem. Remarkably, while “Hot Fun in the Summertime” was at number two, The Temptations’ “I Can’t Get Next to You,” heavily influenced by Sly’s sound, was at number one, demonstrating Sly’s profound influence on the musical landscape.

Then came Woodstock. Initially facing a sleepy, exhausted audience in the early hours of the morning, Sly & The Family Stone’s energy gradually ignited the crowd. Their extended medley of hits, lasting twenty minutes, culminated in audience participation, transforming the tired crowd into a vibrant, engaged mass. Rolling Stone’s review lauded their performance as the highlight of the day, declaring them the victors of the “Battle of the Bands.”

Woodstock arguably marked the zenith of Sly & The Family Stone’s career. They had reached unprecedented heights, both musically and culturally. However, like Icarus, their ascent was followed by a precipitous fall.

Descent and Disintegration: Drugs, Discord, and Decline

The seeds of Sly & The Family Stone’s decline were sown amidst their success. Interpersonal tensions within the band, fueled by drug use and shifting dynamics, began to unravel their unity. Larry Graham’s relationship with Rose Stone dissolved amidst romantic entanglements with Sly’s associates, creating friction. Sly’s sister Loretta, involved in the band’s business affairs, pushed for Kapralik’s removal, further straining relationships.

Relocating to Los Angeles, the epicenter of the entertainment industry and the cocaine trade, exacerbated their drug problems. Cocaine became a central issue, particularly for Sly and Freddie, deepening the divide within the band.

Kapralik established Stone Flower, a production company for Sly, but it yielded limited success, except for two Top 40 hits for Little Sister, “You’re The One” and “Somebody’s Watching You.” These tracks, however, hinted at Sly’s increasing reliance on drum machines and solo recording, foreshadowing the band’s fragmentation.

Between 1967 and 1969, they had released four albums. In late 1969, they released two non-album singles, “Hot Fun in the Summertime” and “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” the latter becoming their second number one hit. “Thank You,” while celebratory, also hinted at a more paranoid outlook, reflecting Sly’s evolving state of mind. It would be the last single featuring the classic lineup and their last new recording for nearly two years.

Sly’s creative process became increasingly solitary and erratic. He envisioned ambitious projects, including a play to complement an album, but struggled to realize them. Cocaine became a major impediment, hindering his productivity and fracturing his relationships with bandmates. He began multitracking recordings himself, using drum machines and session musicians, further isolating himself from the band.

During this period, the band lived together in a mansion previously owned by John and Michelle Phillips, complete with a secret recording studio. However, the communal living arrangement became strained, with Sly’s behavior becoming increasingly erratic and stressful. Sessions became drug-fueled jams with friends like Miles Davis and Johnny “Guitar” Watson, often at the expense of band cohesion.

Sly’s close friendship with Terry Melcher and Bobby Womack, both figures with complex and sometimes controversial reputations, further contributed to the band’s internal turmoil. His renewed association with Billy Preston resulted in co-writing an instrumental B-side, “As I Get Older,” produced by Ray Charles, but these collaborations were overshadowed by the band’s internal decay.

Touring became increasingly problematic, marked by Sly and Freddie’s chronic lateness and no-shows. Management resorted to private planes to get them to gigs, often in vain. Rumors of deliberately sabotaged concerts by political figures, like the alleged Chicago incident orchestrated by Mayor Richard J Daley, further clouded their reputation.

Kapralik, overwhelmed by Sly’s escalating drug use and erratic behavior, relinquished his management role, acknowledging his inability to control Sly’s self-destructive spiral. Larry Graham’s departure followed, fueled by personal and professional conflicts, marking a critical fracture in the band’s core.

“There’s a Riot Goin’ On” and the Final Years

The album There’s a Riot Goin’ On, released in 1971, became a stark reflection of Sly’s deteriorating mental state and the band’s fragmentation. Originally intended to be titled Africa Talks To You, the album’s title and cover – a blacked-out American flag – signaled a radical shift in tone.

Greg Errico was the first to leave during the album sessions, citing the increasingly “ugly” atmosphere within the band. He was replaced by Gerry Gibson, a session drummer known for his work with The Banana Splits, considered by some to be a less skilled drummer than Errico. Gibson’s audition track, “(You Caught Me) Smilin’,” became the final take, highlighting the album’s often improvisational and sometimes haphazard recording process.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On was largely pieced together from overdubs and retakes, with band members rarely recording together. Larry Graham, who departed during the sessions, noted that he never played simultaneously with other band members and that Sly often replaced his bass parts. The album’s murky, lo-fi sound was a result of both artistic choice and the degradation of tapes from repeated recording and erasing.

The lead single, “Family Affair,” featured Sly on most instruments, with minimal contributions from other band members, signaling the band’s functional dissolution. Despite its dark and introspective tone, “Family Affair” went to number one, as did the album, demonstrating Sly’s continued commercial power, even amidst personal and artistic turmoil.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On is often viewed as a socially conscious album, but its primary focus is the portrayal of a mind in breakdown. Oppressive, dark, and gloomy, it’s a deeply personal and idiosyncratic work, bordering on outsider art. Its lo-fi aesthetic and raw emotionality profoundly influenced subsequent generations of Black musicians, most notably Prince.

By this point, those around Sly began to perceive him as two distinct personas: “Sylvester Stewart,” the creative genius, and “Sly Stone,” the self-destructive force. Kapralik, in his own spiral, described his relationship with Sly as “unbearable,” relinquishing management to escape the destructive vortex.

Larry Graham formed Graham Central Station, achieving R&B and pop success, and later converted to the Jehovah’s Witness faith, influencing Prince’s conversion as well. Sly & The Family Stone continued with new members, releasing Fresh in 1973, which also reached the top ten and featured their last Top 20 hit, “If You Want Me To Stay.” The album also included a cover of “Que Sera Sera,” a curious inclusion prompted by Sly’s friendship with Terry Melcher and encounter with Doris Day.

However, Sly’s personal life spiraled further. A publicity stunt wedding to the mother of his child quickly dissolved. Their 1974 album, Small Talk, considered their first truly weak album, signaled the end. A disastrous Radio City Music Hall performance, playing to near-empty seats, confirmed their decline. The original Sly & The Family Stone effectively dissolved, not with a breakup, but with a whimper.

Legacy and Lingering Echoes

Sly Stone continued as a solo artist, releasing a few albums under the Sly & The Family Stone name with ersatz lineups, none capturing the magic of the original band. Cynthia Robinson remained by his side, even in periods of creative inactivity and personal turmoil. Other band members pursued diverse paths. Freddie Stone became a pastor, Rose Stone a successful backing vocalist, and Jerry Martini and Cynthia Robinson briefly joined Graham Central Station.

A brief reunion of the original lineup (minus Graham) occurred at the 2006 Grammys, but Sly’s erratic performance underscored the band’s fractured state. Attempts at a full reunion faltered, and while a new lineup called Family Stone, featuring Sly’s daughter Phunne Stone, toured and recorded, Cynthia Robinson’s death in 2015 marked the end of an era.

Sly released a final album of remakes in 2011, met with little fanfare. Revelations of his financial struggles and life in a mobile home painted a stark picture of his later years. Despite repeated comeback attempts and collaborations, Sly’s health and personal issues continued to overshadow his musical legacy.

In recent years, Sly has achieved some measure of stability and contentment, releasing an autobiography and winning back some of his lost finances. While health limitations prevent touring, he reportedly finds joy in family life.

The career of Sly & The Family Stone, though tragically curtailed by drugs, mental illness, and internal strife, left an indelible mark on music history. Their innovative fusion of funk, soul, and rock, embodied in anthems like “Dance to the Music” and “Everyday People,” profoundly influenced generations of musicians. From Prince and Michael Jackson to Talking Heads and Red Hot Chili Peppers, their sonic DNA is undeniable. Sly Stone’s fall from grace was steep, but his musical ascent took us higher, forever changing the landscape of popular music.

Discover more from A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.