The Ghost Dance, a spiritual movement that swept through Western American Indian communities in the late 19th century, remains a poignant chapter in Native American history. Rooted in visions of hope and renewal, the Ghost Dance promised a world free from suffering and the restoration of ancestral lands and ways of life. This article delves into the origins, beliefs, practices, and tragic consequences of the Ghost Dance movement, highlighting its enduring significance.

The seeds of the Ghost Dance were sown in the late 1860s with the visions of Wodziwob, a Paiute elder. Amidst the devastation of European diseases and encroachment, Wodziwob’s prophecies offered solace and hope. He spoke of a coming cataclysm that would remove European settlers, leaving a pristine world for Native peoples. Later visions softened, foretelling a peaceful, immortal existence for those who adhered to traditional spirituality. Central to Wodziwob’s teachings was a communal circle dance, a practice that resonated deeply with indigenous traditions.

Wodziwob’s influence waned after his death in 1872, but the embers of his vision were rekindled in 1889 by Wovoka, also known as Jack Wilson, a Northern Paiute. During a solar eclipse on January 1, 1889, Wovoka experienced a profound dream. His prophecy echoed Wodziwob’s, envisioning the disappearance of European settlers, the return of buffalo herds, and the restoration of Native lands. Ancestors would return to life, and peace would reign. Raised in a European American household, Wovoka incorporated elements of Christianity into his teachings, sometimes referencing Jesus or a messianic figure. He emphasized peaceful coexistence with white Americans and proclaimed that the Ghost Dance ceremony would usher in this transformative era.

News of Wovoka’s prophecies spread rapidly across tribal lines. Representatives from various tribes journeyed to meet him, and letters circulated, disseminating the vision and the ceremonial dance. Leaders traveled to different nations to teach the Ghost Dance.

The Ghost Dance ceremony was intrinsically linked to existing Native American dance traditions. It drew heavily from the round dance, a widespread practice used for social gatherings and healing rituals. Participants would join hands, moving in a circle with a shuffling step, swaying to the rhythm of songs. While traditional round dances often featured a central drum, the Ghost Dance typically omitted it, sometimes incorporating a pole or tree at the circle’s center, or sometimes nothing at all. Variations in the dance emerged among different tribes who adopted it.

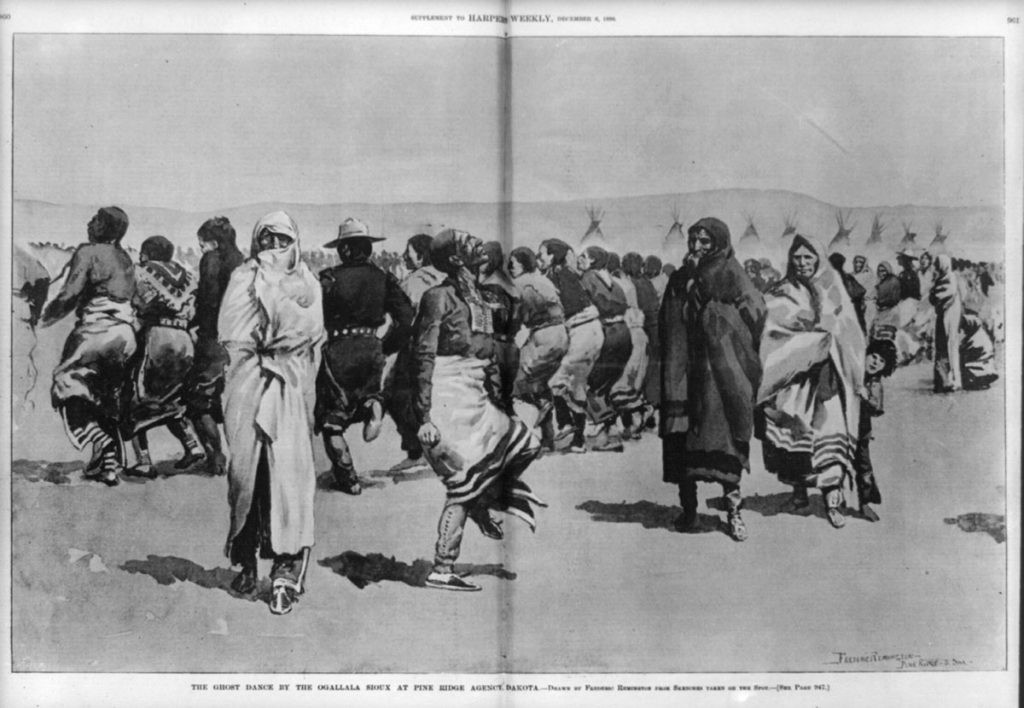

Ethnographer James Mooney, a prominent researcher of American Indian cultures, documented the Ghost Dance extensively. He noted that the dance could induce altered states of consciousness, with some dancers striving for trance-like experiences. To facilitate this, individuals might wave feathers or cloths to focus the dancers’ gaze. Faster-paced songs were employed to aid those seeking trance and visions. Dancers entering a trance might leave the circle to dance individually or lie on the ground, as depicted in Frederic Remington’s illustration accompanying this article, where figures in the foreground seem to be in such a state while others dance in the background.

Ghost Dance songs followed a distinct structure: a line repeated twice, followed by another line repeated twice, and so on. This pattern, common among Paiute and Northwest Plateau peoples, was adopted even by Plains Indians and other groups for whom it was a novel form, as they created Ghost Dance songs in their own languages.

Recordings made by James Mooney in 1894 capture the essence of these songs. These recordings, part of the Library of Congress’s Emile Berliner Collection, offer a valuable glimpse into the soundscape of the Ghost Dance. One example is a Caddo Ghost Dance song, reflecting the Caddo Nation’s participation in the movement.

{mediaObjectId:'517518FC117F012AE0538C93F116012A',metadata:["James Moody. 'Caddo Ghost Dance Song no. 2'"],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

Another recording features Arapaho Ghost Dance songs, showcasing the diversity of musical expression within the movement.

{mediaObjectId:'517518D47350014AE0538C93F116014A',metadata:["James Moody. 'Arapaho Ghost Dance Songs no. 44 and 45'"],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

The rapid spread of the Ghost Dance across diverse and geographically distant Native American communities sparked alarm among European Americans and the U.S. Army. Misinterpreting the movement as militant and warlike, they failed to grasp its true nature: a peaceful, spiritual resistance born from desperation. Treaties had been broken, and Native peoples were confined to reservations. The decimation of buffalo herds, a cornerstone of Plains Indian life, led to starvation and immense hardship. From the Native perspective, European actions were not only destructive to their way of life but also to the very environment.

James Mooney recognized the mischaracterization of the Ghost Dance in the popular press. Hoping to dispel prejudice and misinformation, he published his research, initially as part of an 1890 report and later as a comprehensive book in 1896. Mooney emphasized the peaceful nature of the Ghost Dance, contrasting it with sensationalist newspaper accounts that fueled fears of an Indian uprising. His extensive fieldwork involved travels across thousands of miles and interactions with numerous tribes. He participated in Ghost Dances, documenting the ceremonies and beliefs firsthand through observation, singing, dancing, and photography. Ethnographers of the era were captivated by the Ghost Dance as a rare instance of a new religion emerging and spreading rapidly across cultural and linguistic boundaries.

Mooney traced the Ghost Dance’s ideological roots to earlier prophetic traditions among various Native American groups, traditions that foretold the restoration of land and the return to pre-colonial life. These prophecies had arisen soon after European colonization began, indicating a long-standing yearning for renewal and justice. The Ghost Dance, therefore, was not a sudden eruption but rather a culmination of enduring hopes and beliefs.

Tragically, the Ghost Dance became intertwined with one of the darkest episodes in American history: the Wounded Knee Massacre. On December 15, 1890, tensions surrounding Ghost Dance practices led to the killing of Chief Sitting Bull by police at Standing Rock Reservation. Subsequently, a group of over 300 Miniconjou Lakota, led by Chief Spotted Elk (Big Foot), sought refuge at Pine Ridge Reservation. They were intercepted by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee Creek. As soldiers disarmed the Lakota men, gunfire erupted. The events remain contested, but the outcome was devastating. Estimates suggest that between 150 and 300 Lakota people, many unarmed women and children, were killed, including Chief Spotted Elk himself, who was ill and unarmed. The Army suffered 25 casualties.

Mooney meticulously documented the events leading up to, during, and after the Wounded Knee Massacre, including firsthand accounts from survivors and those who arrived at the scene soon after. He attributed discrepancies in death toll figures to the failure to account for those who died from wounds and exposure after the immediate conflict, estimating the total loss at around 300 lives.

In the climate of fear surrounding the Ghost Dance, the Wounded Knee Massacre was initially portrayed as a “battle,” with soldiers hailed as heroes and awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. However, perspectives shifted dramatically with time. Dee Brown’s 1971 book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, and the rise of the Indian civil rights movement brought forth Native American perspectives, leading to a re-evaluation of the tragedy as the Wounded Knee Massacre.

Despite attempts by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to suppress the Ghost Dance, the ceremony persisted into the early 20th century. Ghost Dance songs continue to be part of Native American traditions today. Researchers should note that some historical collections may label these songs as “new religion songs” rather than explicitly as Ghost Dance songs.

The legacy of the Ghost Dance extends beyond its historical context. In 1973, Wounded Knee became the site of a significant protest during the Indian rights movement, underscoring the enduring symbolic importance of the massacre for Native Americans. The spirit of peaceful resistance and hope for justice embodied in the Ghost Dance continues to resonate in contemporary Indigenous activism. Exploring the recordings of Ghost Dance songs offers a profound way to connect with this pivotal movement in Native American history and understand its lasting impact.

Notes