The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, finalized in September 1830, stands as a stark landmark in the history of the United States and the Choctaw Nation. This agreement, born from the newly enacted Indian Removal Act of 1830, marked the commencement of forced relocations of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands in the East to territories west of the Mississippi River. For the Choctaw people, the treaty meant relinquishing control over their vast communal lands in central Mississippi and west-central Alabama, an area exceeding 10 million acres, to the U.S. government. The lands ceded in Alabama included present-day Livingston and territories west of the Tombigbee River.

Pushmataha, a Choctaw chief who initially resisted the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.

Pushmataha, a Choctaw chief who initially resisted the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.

In the decades following the American Revolution, the Choctaw and Creek nations in the Southeast were compelled to cede substantial territories to the burgeoning United States. These cessions were instrumental in the creation of the Mississippi Territory in 1798. By 1818, the territory was divided, giving rise to the state of Mississippi and the Alabama Territory. Soon after this division, the U.S. government, in concert with Mississippi state officials, began aggressively pursuing treaty negotiations with the Choctaw. The aim was clear: to remove the Choctaw, whose traditional lands encompassed a significant portion of present-day east-central Mississippi and west-central Alabama, to lands west of the Mississippi River.

The initial attempt at removal in 1818 met with firm resistance from the Choctaw people, who unanimously opposed abandoning their homelands. However, U.S. representatives, including figures like General Andrew Jackson, Mississippi State Senator Daniel Burnett, and U.S. Indian agent John McKee, returned in August 1819, undeterred, to resume negotiations with Choctaw leadership. It was during these renewed discussions that the esteemed Choctaw chief Pushmataha, a veteran who had led Choctaw forces in support of the U.S. during the War of 1812 and the Creek War of 1813-14, delivered a powerful and eloquent rejection of the U.S. proposal. He resolutely refused to trade Choctaw ancestral lands in Mississippi for new, unfamiliar lands west of the Mississippi River.

Frustration mounted among Mississippi officials due to the Choctaw’s steadfast refusal to negotiate their removal. Mississippi authorities pressured the federal government to take decisive action to extinguish Choctaw land titles, which the state considered an impediment to its expansion. Andrew Jackson, a staunch advocate for Indian removal, responded to this pressure. He urged Secretary of War John C. Calhoun to authorize him to lead yet another round of negotiations. Empowered with this authority, Jackson, accompanied by Mississippi representatives Christopher Rankin and General Thomas Hinds, employed tactics of intimidation and persuasion to coerce Choctaw chiefs into signing the Treaty of Doak’s Stand in October 1820. Jackson’s approach centered on portraying the U.S. government as acting in the best interests of the Choctaw people, a deceptive tactic to mask the true intent of land acquisition. This treaty resulted in the Choctaws ceding approximately half of their remaining Mississippi lands to the United States. In exchange, they were promised nearly 13 million acres in southwest Arkansas, lands recently acquired by the U.S. from the Quapaw tribe. However, the ink was barely dry on the treaty before white settlers began to encroach upon the newly ceded Choctaw lands in Mississippi. They quickly established Hinds County in the area and named their new state capital Jackson, further solidifying their claim and influence.

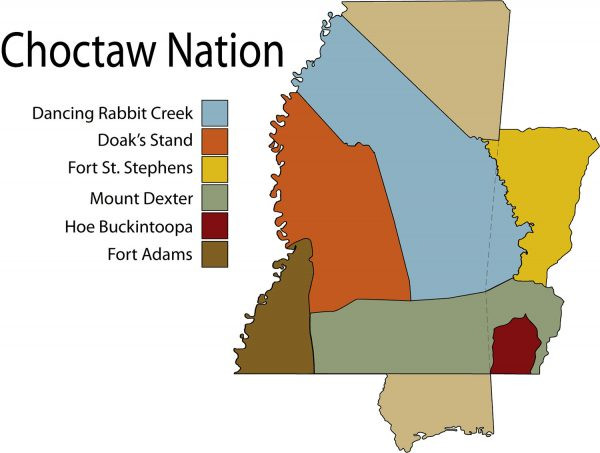

Map showing Choctaw land cessions in Mississippi and Alabama before and after the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.

Map showing Choctaw land cessions in Mississippi and Alabama before and after the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.

Problems with the Treaty of Doak’s Stand quickly surfaced, particularly concerning the Arkansas lands promised to the Choctaws. Non-Native settlers had already begun to occupy these lands, creating immediate conflicts and uncertainty. In response, a Choctaw delegation traveled to Washington, D.C., in late 1824 to seek a resolution. Tragedy struck during this mission when leading chiefs Apuckshunubbee and Pushmataha passed away. The remaining delegates, facing immense pressure, were compelled to cede the eastern portion of the Arkansas lands back to the United States. Despite these treaty negotiations and land cessions, the vast majority of Choctaws remained on their Mississippi lands. State officials continued to intensify their efforts to force their removal.

By 1826, Mississippi Governor Gerard Brandon urged the state legislature to utilize the full force of state power to expel the Choctaws. State legislators even called for the expulsion of missionaries residing among the Choctaws, falsely accusing them of inciting resistance to removal. However, concerns regarding the constitutional division of authority over Indian affairs between state and national governments prevented these extreme measures from being enacted. In 1825, facing persistent threats to their sovereignty, the Choctaw Nation proactively strengthened their governance by establishing a constitutional government, electing leaders, creating a national police force, enacting protections for private property, and establishing a court system. These actions were a clear assertion of their self-determination and a direct response to the escalating pressure for removal.

The election of Andrew Jackson as U.S. president in 1828 fundamentally shifted the landscape for Native American tribes east of the Mississippi River. Even before Jackson’s inauguration in March 1829, the legislatures of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, anticipating a sympathetic administration in the White House, passed laws extending state jurisdiction over all Indian lands within their borders. Jackson’s election ushered in an era of Democratic Party dominance at the national level, accompanied by widespread support for Indian removal. Southern state “extension laws,” as they became known, systematically dismantled tribal governance structures, outlawed communal land ownership, and unilaterally declared Native Americans to be state citizens, stripping them of their tribal affiliations and sovereignty.

Upon assuming office, President Jackson advocated for the voluntary removal of southern Indian tribes while simultaneously championing federal legislation to enforce removal. Exploiting the “constitutional crisis” narrative regarding state versus federal jurisdiction over Indian affairs, Jackson framed Indian removal policy as a necessary solution.

John Coffee, U.S. commissioner at the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek negotiations.

John Coffee, U.S. commissioner at the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek negotiations.

The Indian Removal Act, a cornerstone of Jackson’s policy, became law on May 28, 1830. This act empowered the president to appoint commissioners to negotiate treaties with each eastern Indian tribe. The objective was to secure the relinquishment of their eastern lands in exchange for lands in the Indian Territory, located west of the Mississippi River (present-day Oklahoma and Kansas). The Choctaw Nation was the first to face negotiations under this new act, culminating in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.

In September 1830, over 6,000 Choctaws gathered at Dancing Rabbit Creek in present-day Noxubbee County, Mississippi, to meet with U.S. commissioners Secretary of War John Eaton and General John Coffee, a long-time friend of Jackson and a Tennessee militia leader. Initially, the Choctaw chiefs rejected the proposed treaty terms. A pivotal moment occurred when a group of seven Choctaw women elders, who held positions of significant influence within their matrilineal society and traditionally controlled land access and governance, resolutely refused to consent to the sale of ancestral lands. Their powerful stance temporarily halted the negotiations.

Undeterred, and angered by this resistance, Eaton and Coffee abruptly ceased formal negotiations and instead resorted to clandestine meetings with select Choctaw chiefs, including Greenwood Leflore and Mushulatubbee, who were more amenable to removal. These secret negotiations resulted in a revised treaty document. Crucially, this new version included Article 14, a provision designed to incentivize individual Choctaw men and their families to accept removal. Article 14 allowed them to claim individual allotments of land in Mississippi. These Choctaws could then choose to remain as state citizens on these reduced lands or sell their allotments and use the proceeds to finance their westward migration. A supplementary article further granted additional land allotments to chiefs who signed the treaty and their families, pro-removal Choctaws, and traders to whom the Choctaws were indebted, such as agent George Strother Gaines.

However, the implementation of Article 14 was marred by corruption and incompetence. U.S. land agents, particularly William Ward, tasked with recording Choctaw land claims, largely failed to properly document these claims before the three-year deadline expired. This widespread failure resulted in many Choctaws being unjustly dispossessed of their allotted lands despite the treaty provisions.

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, despite its flaws and the questionable tactics employed to secure it, was formally signed by Choctaw chiefs and U.S. diplomats on September 27, 1830. The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty on February 25, 1831. By late fall 1830, George Gaines initiated the logistical arrangements for the immediate forced immigration of Choctaws to Indian Territory. Over the subsequent years, approximately 13,000 Choctaws endured immense hardship and loss of life as they traveled by wagon, horseback, boat, and on foot. This arduous journey, often referred to as the Trail of Tears in broader context of Indian Removal, led them to Indian Territory, and beyond to Louisiana, Texas, and Tennessee throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries.

Despite the forced removal, around 6,000 Choctaws resisted relocation or later returned to Mississippi and Alabama, striving to maintain their communities. The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians achieved federal recognition as a tribe in 1945, a testament to their resilience. However, in Alabama, the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians continue to seek federal recognition. Despite the profound injustices and ethnic cleansing inherent in the Indian Removal policy and the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, the Choctaw people have persevered. They maintain vibrant communities across the United States, and the Choctaw language and cultural traditions, including stickball, continue to thrive, demonstrating the enduring strength and spirit of the Choctaw Nation.