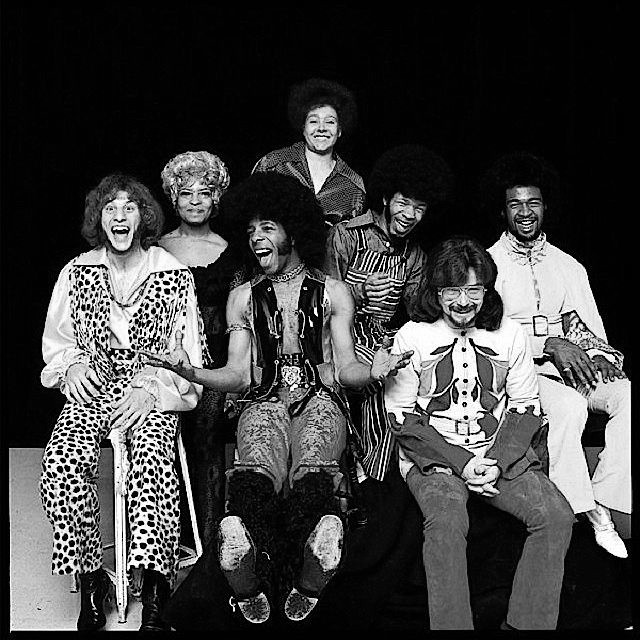

Sly and the Family Stone weren’t just a band; they were a cultural earthquake. Emerging from the vibrant San Francisco scene in the late 1960s, they smashed musical boundaries and societal norms with their electrifying sound. At the heart of their explosive arrival was “Dance to the Music,” a track that wasn’t just a song, but an invitation – a call to unity and uninhibited joy through music. This wasn’t just about dancing; it was about a revolution set to a beat, and “Dance to the Music” was the anthem.

Sly and the Family Stone in their early days, showcasing their diverse lineup

Sly and the Family Stone in their early days, showcasing their diverse lineup

Before the seismic impact of “Dance to the Music,” Sly and the Family Stone were a band in formation, a melting pot of diverse musical backgrounds and experiences. To understand their groundbreaking sound, it’s crucial to delve into the individual stories of the musicians who came together to form this iconic group. Last week’s exploration focused on the Stone/Stewart family and Larry Graham, but the other members were equally vital to the band’s unique chemistry.

Jerry Martini, the saxophonist, honed his skills playing with George and Teddy and the Condors, a band featuring Black singers backed by white musicians, a dynamic that mirrored Sly’s vision for integration. Despite some success, including a performance on Shindig! and a European tour, Martini felt a stronger pull towards Sly’s burgeoning project. Leaving behind a lucrative residency in Las Vegas, Martini chose to gamble on Sly’s vision, a testament to the magnetic force of Sly’s musical ideas. As Martini recounted, “I saw something in Sly and believed in him so much that I gave up my apartment… and went to work for ten dollars a night.”

Greg Errico, the drummer, had previously played with Freddie Stone’s band, Freddie and the Stone Souls, demonstrating his early connection to the Stone family. Before that, he was part of a soul group called the VIPs, showcasing his versatility across genres. Freddie and the Stone Souls even recorded demos produced by Sly, hinting at the future collaboration. One instrumental track, aptly named “LSD” from 1966, provides a glimpse into their early sound explorations.

Cynthia Robinson, a pioneering female trumpeter in a male-dominated era, brought her experience from a bar band that supported touring blues and R&B legends. Her background backing musicians like Lowell Fulson, B.B. King, and Jimmy McCracklin instilled in her a deep understanding of the roots of American music.

While each member brought their individual talents and experiences, none possessed the industry clout or singular vision of Sly Stone. Sly, however, recognized the power in their diverse backgrounds. He was acutely aware of the growing racial divide in music and aimed to bridge this gap. “I played Lord Buckley, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, and Lenny Bruce on an R&B station,” Sly explained, highlighting his commitment to musical inclusivity. He defied genre limitations, declaring, “there ain’t no Black and there ain’t no white and if it comes down to that there ain’t nobody Blacker than me.”

Sly’s ambition was to create a musical tapestry weaving together the melodic innovation of the Beatles, the lyrical depth of Bob Dylan, and the raw funk of James Brown and Otis Redding. He aimed to capture the spirit of the burgeoning white counterculture in San Francisco while staying true to his R&B roots.

While precursors existed, no artist had yet fully synthesized these diverse influences in the way Sly envisioned. The Valentinos, Bobby Womack’s band under Sam Cooke’s guidance, explored targeting the Beat group market. The Chambers Brothers, another family band with a racially mixed lineup, transitioned from folk to rock, foreshadowing Sly’s genre-bending approach. Love, led by Arthur Lee, shared a similar racial mix and a comparable fusion of rock and soul. The 5th Dimension, a Black vocal group known for sunshine pop hits, influenced Sly’s vocal arrangements, a debt acknowledged in their song “Music Lover” which referenced the 5th Dimension’s hit “Up, Up, and Away.”

These contemporaries were inching towards similar sonic territories, but Sly and the Family Stone aimed for a complete amalgamation. They were to be Black and white, feature women instrumentalists, be a vocal group and a rock band, all while incorporating horns and gospel-infused backing vocals. This ambitious vision set them apart and paved the way for “Dance to the Music.”

Initially, Sly and the Family Stone’s live performances leaned heavily on Top 40 covers. Their very first rehearsal centered on “I Don’t Need No Doctor,” a song penned for Ray Charles. However, even in these early stages, Sly’s philosophy of shared spotlight was evident. “I wanted it to be able for everyone to get a chance to sweat,” Sly articulated, emphasizing equality and collective experience within the band.

Their live shows were meticulously structured to showcase each member’s individuality. Opening with Greg Errico’s drum solo, each band member would gradually join the stage, sometimes even emerging from the audience. “The Riffs,” an instrumental piece comprised of jazz riffs in various keys and time signatures, highlighted their musical discipline and cohesion.

Early sets flowed seamlessly, songs merging into one another without interruption. Their repertoire, primarily soul and R&B hits, was strategically chosen to provide solo opportunities for each member. Larry Graham, with his Lou Rawls-esque voice, tackled “Tobacco Road.” Freddie Stone delivered a rendition of “Try a Little Tenderness” reminiscent of Otis Redding. Cynthia Robinson showcased her blues prowess with “St James’ Infirmary,” and Jerry Martini took center stage with the instrumental sax part of Junior Walker’s “Shotgun.”

Their initial performances took place at The Winchester Cathedral, a venue owned by Beau Brummels’ former manager Rich Romanello, who briefly managed the band. The Winchester Cathedral, known for garage rock acts like the Chocolate Watchband, became an unexpected launching pad for Sly and the Family Stone. Their growing popularity allowed them to introduce original material into their sets.

Their first original, “I Ain’t Got Nobody (For Real),” vividly illustrates the band’s collaborative nature. Sly’s original demo was a slow Latin jazz piece, but the band transformed it. In early 1967, they recorded four demos, including a revamped “I Ain’t Got Nobody (For Real).” Despite not paying the studio bill, these demos surfaced later, revealing the song’s metamorphosis. The melody and lyrics remained, but the band’s contributions reshaped the track into something entirely new, highlighting their collective musical identity.

Early recording session showcasing the band's collaborative spirit

Early recording session showcasing the band's collaborative spirit

Shortly after these recordings, David Kapralik entered the picture. A record executive with a paradoxical blend of conventionality and eccentricity, Kapralik, who described himself as “a middle-class New York-born humanist liberal Jewish prince,” had a history of signing major artists like Andy Williams and Barbra Streisand at Columbia Records. He also orchestrated Muhammad Ali’s novelty album, “I Am the Greatest.” Yet, Kapralik also played a pivotal role in pairing Tom Wilson with Bob Dylan, a move that significantly shaped rock music history.

Despite his successes, Kapralik’s career took a turn when he attempted to fire John Hammond, a legendary figure in the industry. While Kapralik claimed complaints from Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin fueled his decision, the move backfired. Hammond, with his deep industry connections, appealed to CBS CEO William Paley, leading to Kapralik’s dismissal instead.

Kapralik transitioned into production and management, finding success with Peaches & Herb. Record promoter Chuck Gregory directed him towards Sly and the Family Stone. Kapralik was immediately captivated. Mutual respect existed; Sly knew of Kapralik’s executive background, and Kapralik recognized Sly’s production talents. A partnership quickly formed.

Kapralik’s fascination with Sly bordered on obsession. He became intensely invested in Sly’s approval, readily prioritizing Sly’s desires, even against his own interests. This dynamic would prove significant in the band’s trajectory.

Kapralik secured a residency for the band at the Pussycat A-Go-Go in Las Vegas, one of the few venues at the time embracing rock acts. Sly and the Family Stone quickly became the must-see act in Vegas, drawing attention from established artists like James Brown, the 5th Dimension, Nino Tempo, and Bobby Darin.

However, the Vegas residency was abruptly cut short due to racial tensions and Sly’s interracial relationships, which clashed with the racist owner’s prejudices and organized crime connections. The band had to leave Las Vegas hastily.

Prior to their Vegas exit, they had already begun recording their debut album. Kapralik, having been rehired by CBS as head of A&R for Epic Records under Clive Davis, signed Sly and the Family Stone to Epic. Davis, newly converted to countercultural rock after attending the Monterey Pop Festival, was eager to sign San Francisco bands. The band utilized their Mondays off during the Vegas residency to fly to LA, record for 24 hours, and return to Vegas.

“Underdog,” the opening track of their debut album, was another pre-band composition by Sly, initially recorded by The Beau Brummels but unreleased. Sly’s revised version captured the summer of 1967 mood. The intro, reminiscent of The Beatles’ “All You Need is Love” with its Marseillaise excerpt, likely inspired the band to incorporate a traditional French tune at the album’s outset.

Their debut album, A Whole New Thing, became a musician’s favorite, lauded by figures like Mose Allison and Tony Bennett. Jazz producer Teo Macero reportedly told Kapralik that his artists raved about the record. George Clinton of The Parliaments was profoundly impacted by “Underdog,” inspiring him to explore new musical directions. The album showcased the band’s collective talent, with Larry and Freddie sharing lead vocals, emphasizing Sly’s initial vision of equality within the group.

Despite critical acclaim, A Whole New Thing commercially flopped. “Underdog,” the debut single, performed so poorly its release status remains ambiguous. Sly, at this juncture, was a “musician’s musician” – a studied composer applying complex musical ideas to soul and rock, but lacking mainstream appeal. Rock critics, often misinterpreting musical innovation, further hindered their initial reception. Rolling Stone’s review criticized it as “more a production than a performance,” ironically mischaracterizing A Whole New Thing as the only album primarily recorded live.

CBS, however, remained confident in Sly and the Family Stone’s hit potential. Following the Vegas incident, the band relocated to New York, securing a residency at the Electric Circus. Rose Stone joined the band, solidifying the classic lineup and adding another female instrumentalist.

Sly described Rose’s crucial role: “Rose is the electric piano player, singer, dancer, and anything else I need… when Rose joined the group everybody was doing everything on stage.” While Rose’s addition was vital, commercial success still eluded them. Davis and Kapralik urged Sly to create something relatable, danceable, a pop single. They suggested he revisit his earlier dance-oriented productions.

Sly responded with “Dance to the Music.”

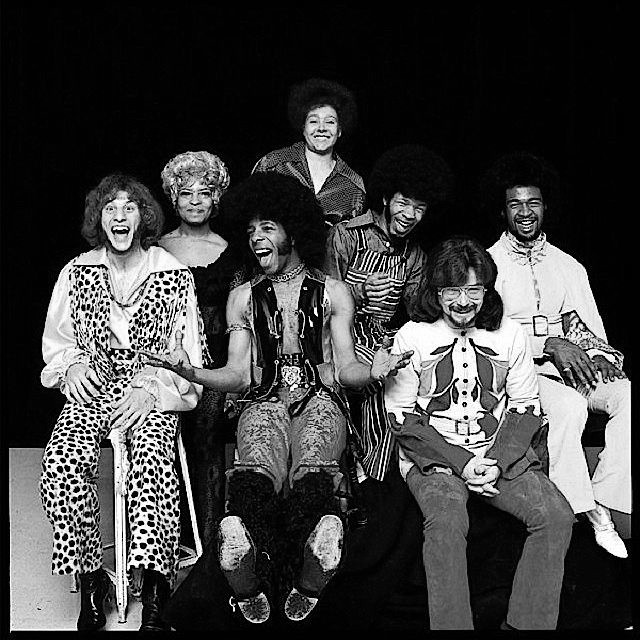

Sly and the Family Stone in their early days, showcasing their diverse lineup

Sly and the Family Stone in their early days, showcasing their diverse lineup

“Dance to the Music” was conceived as a direct response to record label pressure for a hit single. Jerry Martini and others felt it marked a compromise of their artistic vision. Martini later recalled, “Sly threw it down and he looked at me and said, “Okay, I’ll give them something.” And that is when he took off with his formula style. He hated it. He just did it to sell records.” Martini perceived the album Dance to the Music as formulaic, with “glorified Motown beats” that deviated from their earlier, more experimental sound.

While arguably more commercial, “Dance to the Music” and subsequent albums were far from formulaic. If there was a formula, Sly and the Family Stone invented it themselves. “Dance to the Music” incorporated elements from various sources. “Ride, Sally, ride” echoed “Mustang Sally.” The song’s structure, introducing instruments sequentially, mirrored their live show introductions and King Curtis’ recent hit, “Memphis Soul Stew.”

The “Boom boom booms” originated from a stage mishap where Sly, forgetting lyrics, improvised “boom boom boom,” which the band then harmonized, becoming a signature live element incorporated into the recording.

A final sonic element arose from musician union session fees. Jerry Martini, attending an overdubbing session despite already recording his saxophone parts, brought a clarinet instead of a saxophone for convenience. While “noodling” backstage, Sly decided the clarinet’s sound fit the track, making “Dance to the Music” possibly the first soul hit to feature clarinet as a lead instrument. Martini’s clarinet work became a recurring element in their subsequent releases.

“Dance to the Music” became a Top Ten hit in Spring 1968, instantly influencing other musicians. Otis Williams of The Temptations, upon hearing Sly’s music, suggested to Norman Whitfield that this new style was worth exploring. Whitfield, initially dismissive, soon had The Temptations recording “Cloud Nine,” adopting Sly’s style, including social commentary, wah-wah guitar, call-and-response vocals, “boom-boom” backing vocals, and even a nod to the 5th Dimension with “up, up and away.”

This fusion, pioneered by Sly and the Family Stone and embraced by Whitfield, blending San Francisco hippie music with soul, became known as “psychedelic soul,” dominating Black music for much of the following decade.

Their second album, Dance to the Music, named after the hit single, was more cohesive than their debut, emphasizing danceable tracks like “Ride the Rhythm” and the medley “Dance to the Medley.” It also featured “Higher,” Sly’s first reinterpretation of “Advice,” a song he wrote for Billy Preston. “Higher” subtly acknowledged Jackie Wilson’s “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher” in its intro.

Despite the hit single and commercial intent, the Dance to the Music album achieved only moderate commercial success, reaching number eleven on the R&B albums chart and number 142 on the pop charts. However, the song “Dance to the Music”‘s popularity allowed for playful offshoots, like a French version released under the name The French Fries, “Dance a La Musique.”

Recorded in New York, their time there marked a shift in the band’s dynamic. Their Fillmore East debut in May 1968, supporting the Jimi Hendrix Experience, was pivotal. David Kapralik observed, “Up to that point, each individual member had their star piece… At the Fillmore, he decided that it was going to be a one-man show and everybody else was going to back him up, and he took away all their solos.” While not a complete and immediate change, Sly gradually became the central focus, shifting from Sly and THE FAMILY STONE to SLY and the Family Stone.

Despite the shift in focus, the Fillmore East performance was a triumph. Knowing they needed to impress a Hendrix audience, they put on a spectacular show. Sly, Freddie, and Larry jumped into the audience during “Hambone,” leading the crowd in a procession out of and back into the theater, while Cynthia and Greg Errico maintained the rhythm.

Another significant change occurred that night: Jerry Martini witnessed Freddie Stone using cocaine for the first time. New York became the period when cocaine became a major factor in the band’s life. While drugs like heroin, amphetamines, and LSD were prevalent in the 1960s music scene, cocaine’s influence surged as the decade transitioned into the 1970s. Sly Stone, ahead of the curve, and several band members had begun using cocaine in 1967, becoming heavy users by 1968.

Cocaine’s effects, stemming from its disruption of dopamine reuptake, would profoundly impact Sly and the Family Stone. Initially causing euphoria, increased energy, and suppressed appetite, prolonged cocaine use can lead to psychosis, hallucinations, mood swings, and paranoia. It rewires the brain’s stress response, increasing anxiety when not using, creating a cycle of dependency.

Cocaine’s influence began to manifest in the band’s behavior, particularly Sly’s. The follow-up single to “Dance to the Music,” “Life,” underperformed, but its B-side, “M’Lady,” surprisingly charted in the UK. To promote it, and capitalize on “Dance to the Music”‘s success, they toured the UK. A UK tour incident involving Larry Graham being arrested for marijuana possession marked the beginning of escalating problems.

Equipment delays and substandard rented equipment provided by promoter Don Arden further compounded issues. Arden, known for intimidation tactics, threatened the band when they refused to perform with malfunctioning equipment at the first promo gig. Sly addressed the audience directly, explaining the situation and opting for audience engagement over a compromised performance.

“Life,” the B-side’s A-side, became the title track of their third album, Life, released less than a year after their debut. Life represented a shift from the pure party vibe of Dance to the Music toward a more experimental, hippie-oriented sound. Songs like “Plastic Jim” referenced The Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” and The Mothers of Invention’s “Plastic People.”

The Mothers of Invention served as a sonic and thematic touchstone for Life. Tracks like “Jane is a Groupee,” with its fuzz guitar and misogynistic lyrics, echoed Zappa’s style. While horn-driven sounds became synonymous with soul, a brief trend of rock bands with horn sections, like The Buckinghams and Blood, Sweat & Tears, existed at the time. Life targeted the white rock market, which largely ignored it. Neither the album nor its singles achieved commercial success. It appeared Sly and the Family Stone might be a one-hit wonder.

However, “Dance to the Music”‘s enduring popularity secured them an appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Their performance featured a medley of “Dance to the Music,” “Music Lover,” and “I Want to Take You Higher,” including a segment where Sly and Rose interacted with the largely white, older, and reserved audience.

At the medley’s end, Sly’s phrase, “Thank you for letting us be ourselves,” foreshadowed a future hit. More significantly, the medley’s beginning previewed a new song: “Everyday People.”

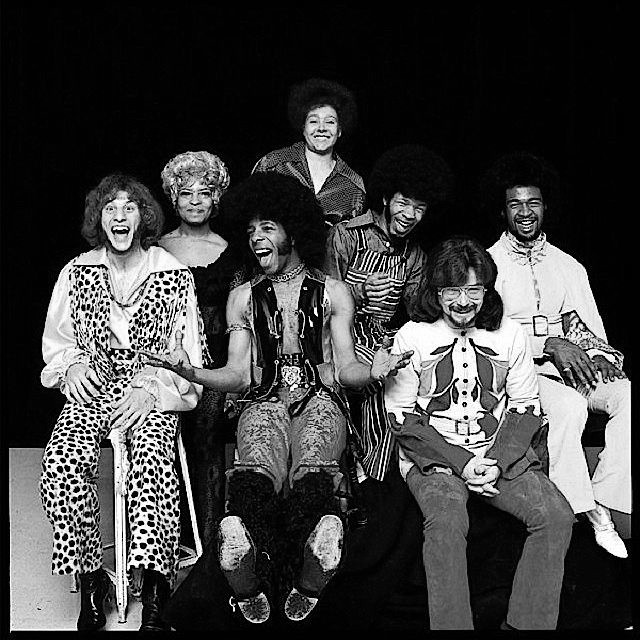

Sly and the Family Stone in their early days, showcasing their diverse lineup

Sly and the Family Stone in their early days, showcasing their diverse lineup

“Everyday People” was meticulously crafted for mass appeal. Built around Larry Graham’s single-note slap bass line, a two-chord structure, and a simple “na-na-na-na-na” melody, it was packed with hooks – the horn line, the “I am everyday people” chorus, and the “We got to live together” counter-vocal. Sly aimed for it to become a standard, like “Jingle Bells” or “Moon River,” emphasizing simple melody and arrangement.

The song’s message, delivered in the final verse, addressed racial intolerance with an optimistic viewpoint characteristic of the late 1960s, a period of perceived progress in civil rights. “Black and white could live together, so long as they just accepted everyone’s differences, and everyone had the same chances now,” was the prevailing sentiment of hope.

Sly articulated his philosophy: “Either everything’s fair or nothing’s fair. Either everybody gets a chance to do what he wants or… you know what I mean?” This message of universality extended beyond race, encompassing their hippie following.

In the late 1960s, hippies and the Civil Rights movement seemed natural allies, both facing societal conservatism. However, the superficiality of some hippie radicalism would become apparent later. In November 1968, the month Nixon won the presidency, “Everyday People” offered both a reflection of societal tensions and a hopeful vision of the future.

“Everyday People” reached number one, holding the top spot for a month and selling a million copies. Billboard ranked it as the fifth biggest hit of 1969. Sly’s aspiration for it to become a standard materialized. Cover versions spanned genres and artists, from The Staple Singers and The Four Tops to Dolly Parton and Peggy Lee. Peggy Lee’s 1969 cover is a particularly odd and fascinating example of the era’s cross-genre musical interactions.

“Different strokes for different folks,” a line from the song, entered the cultural lexicon, mirroring “Respect”‘s impact with “sock it to me.”

The B-side, “Sing a Simple Song,” also charted. Their next single, “Stand!,” the title track of their following album, reached number twenty-two. “Stand!” marked a shift towards studio experimentation. Dissatisfied with initial reactions to a test pressing, Sly added a new tag with session musicians when band members were unavailable, highlighting his growing studio control.

The B-side, “I Want to Take You Higher,” a third iteration of “Advice,” became another hit, even as a B-side. “I Want to Take You Higher,” with its “Boom lakalakalaka” vocals and a Doors reference, became another widely covered song, notably by Ike and Tina Turner.

Stand!, their fourth album in eighteen months, showcased their continued creativity. Despite the overlong instrumental jam “Sex Machine,” the album was packed with hits. Tracks like “Don’t Call Me N—-r, Whitey” displayed a more confrontational approach to racial issues. NME hailed them as a “hard rock group which weaves not only exciting instrumental patterns but vocal ones as well.” Stand! went gold and charted for two years, a significant leap in commercial success.

Despite prolific output, a two-year gap followed before their next album of new material. The summer of 1969 was dominated by festivals. Their festival lineups reflected the era’s eclectic musical tastes, sharing stages with artists from Chuck Berry to the Velvet Underground.

Three festivals stand out: the Harlem Cultural Festival, the Newport Jazz Festival, and the Harlem Apollo. The Harlem Cultural Festival, dubbed “Black Woodstock,” was documented in the film Summer of Soul. Sly and the Family Stone headlined the first show, with security provided by the Black Panthers due to racial tensions.

The Newport Jazz Festival performance is remembered for a riot attributed to the band’s electrifying set. Hundreds broke down fences to get in, leading to police intervention. Their Harlem Apollo dates aimed to solidify their Black audience, addressing concerns about primarily appealing to white rock fans. At the Apollo, Sly confronted racial biases within his own audience, emphasizing the band’s integrated nature.

At the end of July, coinciding with the moon landing, they released “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” another major hit. It reached number two, while Norman Whitfield and The Temptations’ Sly Stone-inspired “I Can’t Get Next to You” held number one, illustrating Sly’s pervasive influence on the musical landscape.

Then came Woodstock. Initially facing a sleepy, late-night crowd, Sly and the Family Stone’s extended medley of hits, lasting twenty minutes, revitalized the audience. Rolling Stone lauded their Woodstock performance as the highlight of the day, surpassing other major acts.

Woodstock marked a peak. However, the seeds of their decline were sown. Interpersonal tensions, drug use, and external pressures began to unravel the band. Larry Graham’s relationship with Rose Stone dissolved amidst Sly’s gangster friend’s interference. Sly’s sister Loretta and associates pushed for Kapralik’s removal and the expulsion of white band members, which Sly resisted, but relationships frayed.

Relocating to Los Angeles, the entertainment industry’s center and a hub for cocaine, exacerbated drug issues, particularly for Sly and Freddie, who grew closer but distanced from the rest of the band.

Kapralik established Stone Flower Productions for Sly, distributed by Atlantic. Despite producing singles for Joe Hicks and 6ix, only Little Sister, another Stone Flower act, achieved success with two Top 40 singles in 1970, “You’re The One” and “Somebody’s Watching You,” a remake of a Stand! track.

By late 1969, Sly’s focus shifted away from band collaboration. He envisioned a multimedia project, integrating music with theater. Cocaine use intensified, hindering his creative process. He increasingly multi-tracked recordings alone, relying on session musicians and drum machines. Little Sister’s “Somebody’s Watching You” is cited as possibly the first Top 40 hit using a drum machine.

The band members, while often living together in a mansion previously owned by John and Michelle Phillips, found Sly increasingly erratic and difficult. Martini described this period as turning him and his wife into “idiots, zombies,” waiting for Sly’s direction amidst drug use.

Sly’s inner circle included talented but troubled musicians who shared his cocaine habit. Miles Davis and Johnny “Guitar” Watson were frequent guests but didn’t record with Sly during this period, contrary to rumors. Sly’s friendships with Terry Melcher and Bobby Womack further illustrate his evolving social circle.

The group continued touring, but Sly and Freddie’s chronic lateness and no-shows became notorious. Management resorted to private planes to get them to gigs, often in vain. Jerry Martini alleged that Chicago Mayor Richard J Daley orchestrated a riot at a Grant Park concert, blaming it on the band’s supposed no-show to suppress concerts.

Kapralik, still managing Sly, was deeply enmeshed in Sly’s chaotic world. He admitted to cocaine use and losing control, describing his relationship with Sly as “unbearable.” He eventually relinquished management to Ken Roberts.

Larry Graham’s departure was precipitated by personal and professional strains. Rose Stone left Graham for Sly’s gangster friend Bubba Banks. Graham formed Graham Central Station, achieving R&B and pop hits, and later converted to and influenced Prince with the Jehovah’s Witness faith.

Sly’s creative output became increasingly solitary. There’s a Riot Goin’ On, initially titled Africa Talks To You, marked a turning point. Greg Errico left early in the sessions, replaced by Gerry Gibson, previously of The Banana Splits. Martini criticized Gibson as “mediocre,” but he played on most of the album, alongside Errico and drum machines.

“(You Caught Me) Smilin’” was Gibson’s audition track, his first take becoming the final version. There’s a Riot Goin’ On was built from overdubs and retakes. Larry Graham described never playing with other band members during recording, with Sly often replacing his bass parts.

The album’s murky sound resulted from deliberate choices and tape degradation from repeated recording. Sly’s erratic studio behavior, including recording and erasing vocals of women he pursued, contributed to the album’s fragmented creation.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On, like The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, is often seen as a solo work, but this understates the band’s contributions. The full band appears on about four of the eleven tracks. The lead single, “Family Affair,” featured Sly, Rose, Bobby Womack, and Billy Preston, but none of the core band except Sly and Rose.

“Family Affair” and There’s a Riot Goin’ On both reached number one, but marked the beginning of the end. The album, despite its title and cover depicting a black American flag, is less overtly political than introspective, portraying a mind in breakdown. Tracks like “Spaced Cowboy” showcased a darker, more fragmented sound.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On is compared to The Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street and John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band in its raw, personal intensity. Sly pioneered a lo-fi aesthetic, influencing Prince and subsequent generations of Black musicians.

Sly’s persona fractured into “Sly” and “Sylvester,” the destructive and creative aspects of his personality. Kapralik described his relationship with Sly as “disintegrating” and “unbearable,” eventually stepping down as manager.

The rhythm section shifted again. Gibson was replaced by Andy Newmark. Larry Graham departed during Fresh sessions. Fresh reached the Top Ten, featuring a cover of “Que Sera Sera,” inspired by Sly’s encounter with Doris Day. Rumors of an affair between Sly and Day circulated.

Larry Graham formed Graham Central Station and achieved further success. The band continued without Graham, adding bassist Rusty Allen and saxophonist Pat Rizzo. Fresh produced their last Top 20 hit, “If You Want Me To Stay.”

Sly’s personal life spiraled. His marriage to the mother of his child, Sylvester Jr., a publicity stunt at Madison Square Garden, quickly dissolved. She left fearing for her child’s safety. Cynthia Robinson became pregnant with Sly’s second child, Phunne.

Small Talk, their 1974 album, featuring Sly, his wife, and Sylvester Jr. on the cover, is considered their first weak album. A Radio City Music Hall run was poorly attended. Freddie Stone described feeling “tasteless, empty,” marking a definitive end.

The original Family Stone unofficially dissolved. Sly released a solo album in 1975, with ersatz “Sly and the Family Stone” projects following, none involving the full original band. Cynthia Robinson remained loyal, continuing to collaborate sporadically with Sly.

Cynthia briefly joined Graham Central Station and played with Prince and George Clinton. Freddie Stone became a pastor. Rose Stone became a backing vocalist. Sly struggled with addiction, legal battles, and comeback attempts. A 2006 Grammy reunion was marred by Sly’s erratic performance.

Without Sly, Cynthia, Jerry, and Greg formed Family Stone with Sly and Cynthia’s daughter Phunne, touring and releasing a single in 2015. Cynthia Robinson passed away shortly after. Phunne and Jerry continue to tour as Family Stone.

Sly released a final album in 2011, revisiting his hits with collaborators, commercially and critically unsuccessful. He faced financial hardship, living in a mobile home. Recent years have seen comeback attempts and collaborations. He released an autobiography in 2023 and a Christmas single. Health issues prevent touring.

Sly and the Family Stone’s career was brief but transformative. Drug abuse and internal conflicts cut short their trajectory, but their impact on music is undeniable. They redefined rock, pop, soul, and funk, influencing Prince, Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Talking Heads, and Red Hot Chili Peppers, shaping disco and New Wave.

Sly Stone’s fall from grace is a cautionary tale, but his musical legacy endures. He took music “higher,” leaving an indelible mark on popular culture.

Discover more from ten-dance.com

Explore more groundbreaking artists and dance anthems that shaped music history. Stay tuned for deeper dives into the evolution of dance music and the cultural movements it inspired.