Jacques Demy’s 1967 film, Les demoiselles de Rochefort, often gets unfairly lumped into the category of “just another musical.” But to dismiss it as the Same Old Song And Dance would be a profound misjudgment. For those willing to look beyond surface-level expectations, this film reveals itself as a shimmering, bittersweet, and utterly unique masterpiece. Having been captivated by its soundtrack for years, finally experiencing the film with subtitles cemented its place as not just a favorite musical, but a cinematic treasure. Shot entirely in the charming French town of Rochefort, this large-scale production pays homage to the grand Hollywood musicals while infusing them with an undeniably French romantic spirit and energy. Michel Legrand’s score is arguably his finest work, a near-constant stream of delightful songs penned by Demy himself. While the choreography may be uneven, ranging from conventional to inspired (especially Gene Kelly’s own contributions), the film’s true brilliance lies in its intricate tapestry of connections – both missed and realized – a feat of storytelling comparable to Shakespeare or Tati’s Playtime.

When we try to categorize movies by genre, The Young Girls of Rochefort defies easy placement. It’s a film that swings with a jazzy rhythm, thanks to Legrand’s score which nods to legends like Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington. Even when the dance sequences are less impressive, Demy’s dynamic camera work – his sweeping cranes, extended pans, and detailed mise en scène – creates a captivating rhythm of its own. This isn’t just the same old song and dance; it’s a vibrant, pulsating cinematic experience.

This image has an empty alt attribute; its file name is 100-1.gif

This image has an empty alt attribute; its file name is 100-1.gif

Furthermore, Demy’s film constantly plays with the conventions of the musical genre, preventing it from ever becoming predictable or formulaic – anything but the same old song and dance. Instead of the rigid symmetry often found in Hollywood musical numbers, Demy allows dancers to move at the edges of the frame, creating a sense of spontaneity and life beyond the central performance. He even incorporates cheerfully upbeat songs about decidedly un-musical topics like an ax murder, subverting expectations at every turn. While paying clear tribute to classic Hollywood musicals like On the Town, An American in Paris, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Demy’s film ultimately feels distinctly French, a testament to his unique vision.

Most musicals adhere to a clear separation between spoken narrative and musical numbers. The Young Girls of Rochefort, however, boldly blurs these lines, interweaving story and song in surprising ways. Characters might be walking down a street, and suddenly the everyday world around them erupts into dance, with the main characters seamlessly joining and leaving the choreography. This innovative approach generates a powerful and complex emotional landscape. It’s a film filled with exuberance, yet tinged with absurdity, and underscored by a constant sense of longing and even tragedy. This blend of seemingly contradictory emotions is far removed from the often simplistic emotional palette of the same old song and dance musicals. This very strangeness, this refusal to conform to easy categorization, might be why some viewers, particularly in America, have struggled to fully embrace its unique charm, dismissing it as camp or esoteric. This difficulty mirrors the initial reception of other unconventional musicals like Love Me Tonight and Hallelujah, I’m a Bum, which similarly prioritize a continuous state of musicality over traditional narrative structures.

While some audiences might find this aesthetic overwhelming, in France, The Young Girls of Rochefort has always been cherished and regularly revived. Agnès Varda, Demy’s widow, even oversaw a restoration in 1996, further cementing its legacy. Varda’s documentary, The Young Girls Turn 25, captures the enduring passion for the film, exemplified by a French teenager who carries the movie’s video alongside Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion – a level of devotion that might seem “demented” in a society focused on practicality, but perfectly in tune with the film’s own passionate spirit. This deep artistic appreciation contrasts sharply with the lukewarm reception in some markets, perhaps explaining why Miramax, for instance, offered minimal advertising support for its Chicago release. It suggests a cultural difference in how audiences approach and value art that deviates from the same old song and dance.

Conventional wisdom often praises musicals for their technical perfection and flawless execution, judging them almost like sporting events or feats of engineering. This quantitative approach leaves little room for appreciating the beauty in imperfection or unconventionality. To apply this metric to The Young Girls of Rochefort would be to miss its point entirely. Critic Gary Carey’s assessment, lamenting Demy’s supposed inability to photograph dance choreography, reflects this limited perspective. Similarly, Pauline Kael, while acknowledging Demy’s talent, suggested the film demonstrated a misunderstanding of American musical conventions and even hinted at creative exhaustion. These criticisms stem from a viewpoint that expects musicals to adhere to a certain formula, to be the same old song and dance perfected, rather than recognizing the value of innovation and personal vision.

Coming after the international success of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, The Young Girls of Rochefort, with its larger budget, could be seen as an ambitious, perhaps even impossible, undertaking if viewed merely as an imitation of Hollywood musicals. But Demy was not aiming for imitation. He was appropriating elements of the Hollywood musical tradition and transforming them through his own distinct artistic lens. Expecting a carbon copy of a Hollywood musical from a French filmmaker with Demy’s background and resources is unreasonable. He possessed a fully formed style and vision, and Les demoiselles de Rochefort is a testament to his unique approach. While an English-language version was filmed for commercial reasons, it’s the subtitled French version that truly captures the film’s essence. Its initial commercial failure in the US sadly hampered Demy’s career, making its rediscovery and appreciation over the past decades all the more rewarding. It proves that true artistry often transcends immediate popular taste and that what might initially seem like a departure from the same old song and dance can ultimately become a timeless masterpiece.

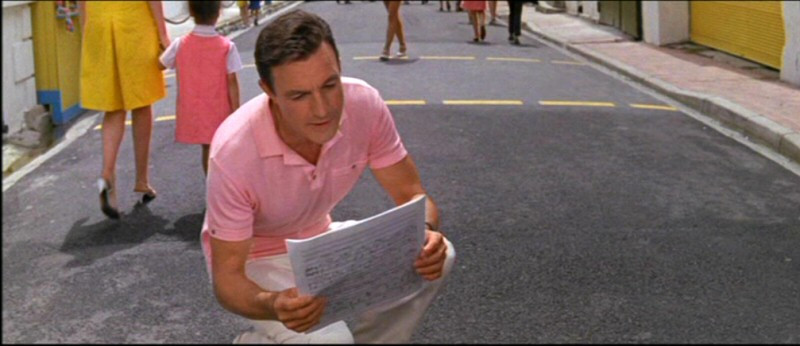

The narrative of The Young Girls of Rochefort unfolds over a single, vibrant weekend. On Friday, a flurry of activity arrives in Rochefort as boat, bicycle, and motorcycle salespeople, including Etienne (George Chakiris) and Bill (Grover Dale), set up for a Sunday fair. The camera gracefully introduces us to Delphine (Catherine Deneuve) and Solange (Françoise Dorléac), twin sisters giving music and dance lessons. We learn they are dreamers, Delphine a dance teacher and Solange a composer, both yearning for romance and a life in Paris. (Adding a poignant layer, Deneuve and Dorléac were real-life sisters, making their on-screen sisterhood even more resonant, tragically, this was their only film together as Dorléac passed away shortly after its release.)

Delphine’s ideal man is Maxence (Jacques Perrin), a painter and sailor stationed in Rochefort, who, unbeknownst to her, has been searching the world for the woman he has painted – a woman who is Delphine’s exact double. His painting hangs in a gallery run by Guillaume (Jacques Riberolles), Delphine’s persistent but unsuccessful admirer. The sisters also have a young half-brother, Boubou, and their mother, Yvonne (Danielle Darrieux), runs the local café, a central meeting point for many characters. Adding another layer of romantic entanglement, Boubou’s father, Simon Dame (Michel Piccoli), Yvonne’s former fiancé, has returned to Rochefort to open a music store. Yvonne had previously refused to marry Simon years ago due to the social awkwardness of the name “Madame Dame,” and Simon is unaware that Solange, who frequents his shop, is one of Yvonne’s daughters.

Fate intervenes when Solange encounters Andy Miller (Gene Kelly), a famous American composer and pianist, while picking up Boubou from school. She is unaware of his identity, but he is captivated by her and inadvertently takes a page of her piano concerto. Meanwhile, when dancers for the Sunday fair drop out, Etienne and Bill persuade Delphine and Solange to perform, promising them a trip to Paris – setting the stage for a weekend of intertwined destinies and near misses. This intricate plot, full of coincidences and desires, is far richer and more engaging than the predictable narratives often found in the same old song and dance musicals.

Beyond the central romantic plots, the film subtly incorporates darker elements – an ax murder and the presence of soldiers – which underscore the theme of thwarted desire. Yvonne’s café serves as the bustling hub where all these interconnected stories unfold. Like the buildings in Tati’s Playtime, the café’s glass walls allow us to observe the constant flow of life around it. The film masterfully depicts characters ideally suited for each other constantly missing connections, often unaware of how close they are to their dreams. Despite its ultimately optimistic conclusion, where everyone finds their match, the film lingers on the poignant near-misses, creating a bittersweet aftertaste. The moment Maxence and Delphine narrowly miss each other at the café is arguably the most heart-wrenching moment in Demy’s filmography, highlighting the film’s emotional depth far beyond the typical happy endings of the same old song and dance. The eventual happy pairings, almost presented as an afterthought, feel like a concession to musical comedy conventions, while the lingering sense of dreams just out of reach truly resonates.

Ultimately, The Young Girls of Rochefort evokes a unique emotional duality – a poetic state of simultaneous mania and melancholy, of despair and exuberance. This is Demy’s characteristic vision of life, present in Lola and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg as well, but amplified in Rochefort through Legrand’s vibrant score and the film’s grand scale.

Demy doesn’t prioritize fantasy (songs and dances) over reality (everyday life), but rather explores their complex interplay. Missed connections represent the often-frustrating reality where daily routines obscure our dreams, while the eventual connections embody the fantasy of musical comedy resolutions. But Demy is a subtle artist; he transforms Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am” into “I dream, and dreaming is part of life, therefore I live.” By filming musical numbers in real locations, he blurs the lines between fantasy and reality, making missed connections as much a product of mise en scène as chance. Demy, a poetic realist and a dreamer, challenges viewers to see a richer, more nuanced reality than typical entertainment offers, a reality that goes far beyond the same old song and dance.

The film’s themes of chance encounters and missed connections are further emphasized through the score and Demy’s lyrical writing. Maxence’s song about his search mirrors Delphine’s song of longing; Simon’s lament about lost love becomes Yvonne’s regretful reflection. Solange’s piano concerto later gains lyrics after Andy discovers the score. Even seemingly minor musical moments, like the song accompanying the policing of the crowd, subtly reprise and add lyrics to themes from the opening dance number, enriching the film’s emotional and thematic tapestry through musical rhymes.

Masterpieces are not necessarily flawless. In fact, some of The Young Girls of Rochefort’s imperfections enhance its lifelike quality and the vulnerability of its characters. (Even the product placements during the fair, reminiscent of Tati’s Playtime, serve as reminders of the practicalities of filmmaking.) Darrieux is the only cast member who sings her own songs, although the dubbing of others is generally well-executed, matching singing and speaking voices. The miming of instruments by Delphine and Solange is more overtly artificial, adding to the film’s charming blend of real and unreal.

Considering Demy’s initial ideas, the film’s final form is remarkable. He considered various French port cities before settling on Rochefort, ultimately choosing it for its central square. Even then, production designer Bernard Evein had to repaint vast areas of the city to achieve the film’s vibrant color palette. Demy’s initial casting ideas were equally surprising – Brigitte Bardot and Geraldine Chaplin were considered for the twin roles.

Demy also intended to include more explicit references to The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, originally casting Nino Castelnuovo. While Castelnuovo’s unavailability led to script changes, Demy subtly wove in connections to his earlier work. The off-screen ax murder victim is named Lola, the protagonist of Demy’s first film, and numerous allusions to his previous films are sprinkled throughout. Critic Jean-Pierre Berthomé notes that the three endings of The Young Girls of Rochefort echo the final shots of Bay of Angels, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and Lola, creating a sense of cinematic continuity. Furthermore, the association of Americans with white convertibles is a recurring motif from Lola.

Gene Kelly’s presence undeniably elevates the film, embodying the joyous spirit inherent in musicals. His energy, alongside Chakiris and Dale, infuses the film with an American dynamism that, combined with the French cast’s sensibility, creates its unique flavor. Much like the pairing of Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo in Godard’s Breathless or David Goodis and Charles Aznavour in Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player, this cultural fusion generates a powerful cinematic alchemy, a vibrant energy that defined the French New Wave and revolutionized filmmaking in the 1960s. While Godard and Truffaut laid the groundwork, Demy, with The Young Girls of Rochefort, cultivated a late-blooming flower, blending Hollywood musical virtues with French poetic realism to create something fresh, colorful, and utterly unforgettable – a film that is anything but the same old song and dance.

This image has an empty alt attribute; its file name is 200w-13.gif

This image has an empty alt attribute; its file name is 200w-13.gif

[