The tale of “Dancing with the Devil” is a chilling narrative deeply embedded in the cultural tapestry of the Texas Borderlands, resonating with the same eerie familiarity as stories of La Llorona or El Cucuy. This folktale, often whispered in hushed tones, speaks of a young woman who, ignoring parental warnings, ventures out on Good Friday and encounters a captivating stranger in a nightclub – a stranger soon revealed to be the devil himself. While the nightclub setting might shift across different versions of the story, sometimes appearing as a school dance or prom, the core message remains starkly consistent. In the Rio Grande Valley, this legendary encounter is often placed at Club Boccacio 2000 in McAllen, Texas, back in 1979. But what is the deeper Dancing With The Devil Meaning? This narrative is more than just a spooky story; it’s a reflection of societal anxieties, cultural norms, and the ever-present dance between tradition and transgression.

The narrative unfolds with a familiar cautionary tone: despite the allure of the mysterious stranger, it’s the young protagonist who dares to accept his dance invitation. The climax is often swift and terrifying – the woman dead by dance’s end, the room filled with smoke, and the horrifying reveal of a hoof or claw in place of a human foot. At its surface, “Dancing with the Devil” seems to be a morality tale steeped in religious and gendered stereotypes. It reinforces obedience, particularly for women, and champions pious femininity, suggesting that ‘good’ girls simply don’t frequent nightclubs. Fear of the unknown, embodied by the monstrous stranger, becomes a central theme, warning against stepping outside the established boundaries of community and tradition. Drawing on the insights of Zygmunt Bauman, the stranger embodies ambiguity, unsettling the lines between ‘us’ and ‘them,’ friend and foe, creating anxiety and disruption. In this context, the dancing with the devil meaning becomes a potent symbol of societal disruption and the consequences of challenging established norms, particularly within the cultural and religious frameworks of the Texas Borderlands during periods of social change like the Chicanx Movement of the 1960s and 70s.

The South Texas Borderlands Context

To truly grasp the dancing with the devil meaning, we must understand the unique context of the South Texas Borderlands. This region, as García describes, is a space profoundly shaped by colonization, a land repeatedly impacted by shifting political orders and ecological changes spanning centuries. The Rio Grande Valley emerged as a distinctive zone within colonized territories, a vibrant cultural and ecological space violently carved into a border between two nations. This imposed border wasn’t merely a line on a map; it became a division between people, languages, identities, and ways of life. The internal tensions and disputes born from this division laid the groundwork for the social anxieties reflected in stories like “Dancing with the Devil.” It was during the Chicanx Movement that the people of this region began to articulate their experiences and strategies for survival within this settler-colonial landscape. How did these realities manifest in the stories they told? Re-examining “Dancing with the Devil” offers a powerful lens through which to explore this question.

María Inés Palleiro’s perspective on folktales highlights their dynamic and evolving nature. She describes them as textual blocks, flexible and fragmentary, connected by loose threads. These narratives, disseminated through storytelling, family histories, and community legends, contribute to the larger, dominant narratives of a culture. However, these blocks are not static; they are living documents, constantly reshaped with each retelling, reflecting the evolving concerns and anxieties of the community. Listening to personal accounts, like the author’s mother’s memories of 1970s Texas Borderlands nightclubs, reveals how these stories construct and reflect reality, and how the transformations inherent within folktales can unveil and even reshape communities. The dancing with the devil meaning, therefore, is not fixed, but rather a fluid concept molded by each telling and each generation within the Borderlands context.

Unearthing Story Fragments: Glazer’s Archival Research

Driven by a quest to understand the origins and enduring power of “Dancing with the Devil,” the author delved into the archives of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV) Library. There, the research of Mark Glazer, a professor from UTRGV’s predecessor institution, the University of Texas-Pan American (UTPA), came to light. Seeking Glazer’s original research, the author encountered an archivist who, while helpful, offered a cautionary warning against delving too deeply into devil-related topics, highlighting the deeply ingrained cultural beliefs surrounding such narratives. This encounter underscored the potent hold the folktale has on the community and further fueled the author’s curiosity about the story’s enduring presence and impact. The question became: how does a story about the devil function to maintain social order, particularly in a culture deeply rooted in religious imagery and family values? How does it discourage women from venturing beyond established boundaries, both physically and metaphorically? The answer, it seemed, lay in the powerful symbolism embedded within the dancing with the devil meaning.

“Dancing with the Devil” persists through generations in South Texas, evolving through oral and textual transmissions. A key characteristic of these retellings is their grounding in supposed eyewitness accounts, transitioning from “someone who was there” to “knows someone who was there,” and finally solidifying into community lore attributed to “what people say.” This attribution to communal wisdom cements the story’s reality within the collective consciousness, granting it lasting power. For Okanagan storyteller Jeannette Armstrong, language itself is a conduit for stories, a collective voice speaking through individuals. Stories are relational, cultural, and deeply rooted in lived experiences. This perspective aligns with cultural rhetorics, which, as Andrea Riley Mukavetz defines, examines how communities create meaning and use communication to disseminate knowledge. Cultural rhetorics scholarship values the practices communities use to sustain themselves and builds theoretical frameworks that reflect the cultural community being studied. The dancing with the devil meaning, in this sense, is not just a simple narrative, but a complex cultural artifact reflecting community values, anxieties, and power dynamics.

Scattered papers and images, South Texas devil-related research, scattered across a desk. Source: Marlene Galván

Scattered papers and images, South Texas devil-related research, scattered across a desk. Source: Marlene Galván

Marlene’s South Texas devil-related research

The author’s research aims to examine how dominant narratives are constructed and maintained through smaller folktale fragments within the Texas Borderlands community. Specifically, it seeks to understand what these fragments reveal about settler-colonial logics and intersecting gendered oppressions, and how storytellers can use cultural rhetorics methodologies to influence or even reshape these dominant narratives. Three narrative fragments of “Dancing with the Devil” became central to this analysis: interviews from Mark Glazer’s (1994) Flour from Another Sack & Other Proverbs, Folk Beliefs, Tales, Riddles & Recipes; José Eduardo Limón’s (1994) autoethnographic account in Dancing with the Devil: Society and Cultural Poetics in Mexican-American South Texas; and a poem from Amalia Ortiz’s (2015) Rant. Chant. Chisme. These fragments, existing within David Boje’s concept of story networks, function as nodes within a larger, evolving narrative. Boje likens these fragments to a “story disassemblage soup,” emphasizing that there is no single, complete story, but rather a collection of perspectives and interpretations. Analyzing these fragments allows us to understand the consistent elements of the dominant narrative and the contextual motivations behind them. The dominant narrative of “Dancing with the Devil” appears straightforward: a disobedient girl, succumbing to temptation, dances with the devil and faces fatal consequences. However, examining these fragments reveals how storytellers and their methodologies shape and potentially transform the dancing with the devil meaning.

Glazer and Limón, while employing different research methods, both attribute the folktale’s popularity to socio-political and economic shifts within Chicanx communities during the 1960s and 70s, and again in the 1990s. However, beyond their findings, the researchers’ methodologies themselves are revealing. Their approaches evoked feelings of distance, ambivalence, and anxiety in their research participants, mirroring the very “stranger” archetype the folktale explores. Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples critiques Western research practices in marginalized communities, highlighting the problematic nature of “research” itself. Marginalized communities, like the Texas Borderlands, are vulnerable to traditional Western research models. Glazer and Limón’s research, whether intentionally or not, contributes to the story’s narrative through their representation and affirmation of Western research methodologies, revealing colonial politics and gendered oppressions at play. The dancing with the devil meaning is further complicated by the lens through which it is examined and retold.

Fragment 1: Glazer’s Objectivity and the “Informant”

Glazer’s Flour from Another Sack & Other Proverbs, Folk Beliefs, Tales, Riddles, & Recipes exemplifies a Western research approach focused on systematic analysis and objectivity. While acknowledging the contributions of students and colleagues, Glazer positions himself as the ultimate authority, responsible for the “final form” of the collected folklore. He aims for a “systematic approach” to documenting Rio Grande Valley culture, emphasizing its previously undocumented richness. His detailed, taxonomic methodology includes charts and classifications, reflecting a desire to categorize and analyze the region’s folklore in a “readable fashion” for an academic audience. This approach, however, aligns with what Smith describes as Western research’s tendency to classify, categorize, and create standards for evaluation, potentially leading to the objectification and dehumanization of researched communities. Glazer’s use of the term “informants” to describe his research participants reinforces this objectification, suggesting they are sources of data for his research, his dominant narrative. Agboka critiques such dehumanizing terms, questioning why “informants” is preferred over more collaborative terms like “participants” or “community members.” The choice of “informants” underscores the project’s goal of an “objective” account of Rio Grande Valley culture, including folktales, further shaping the dancing with the devil meaning within a specific research framework.

Glazer’s collection includes two oral accounts of “Dancing with the Devil.” The first, from a 12-year-old “informant,” emphasizes disobedience to a strict mother’s warning against dancing, highlighting the consequence of defying parental authority. The second account, from a 62-year-old man, adds details about the stranger’s allure and the dramatic climax of his disappearance in a puff of smoke, witnessing the girl’s demise. While variations exist, the core themes remain: female disobedience, temptation by a stranger, and punishment by death.

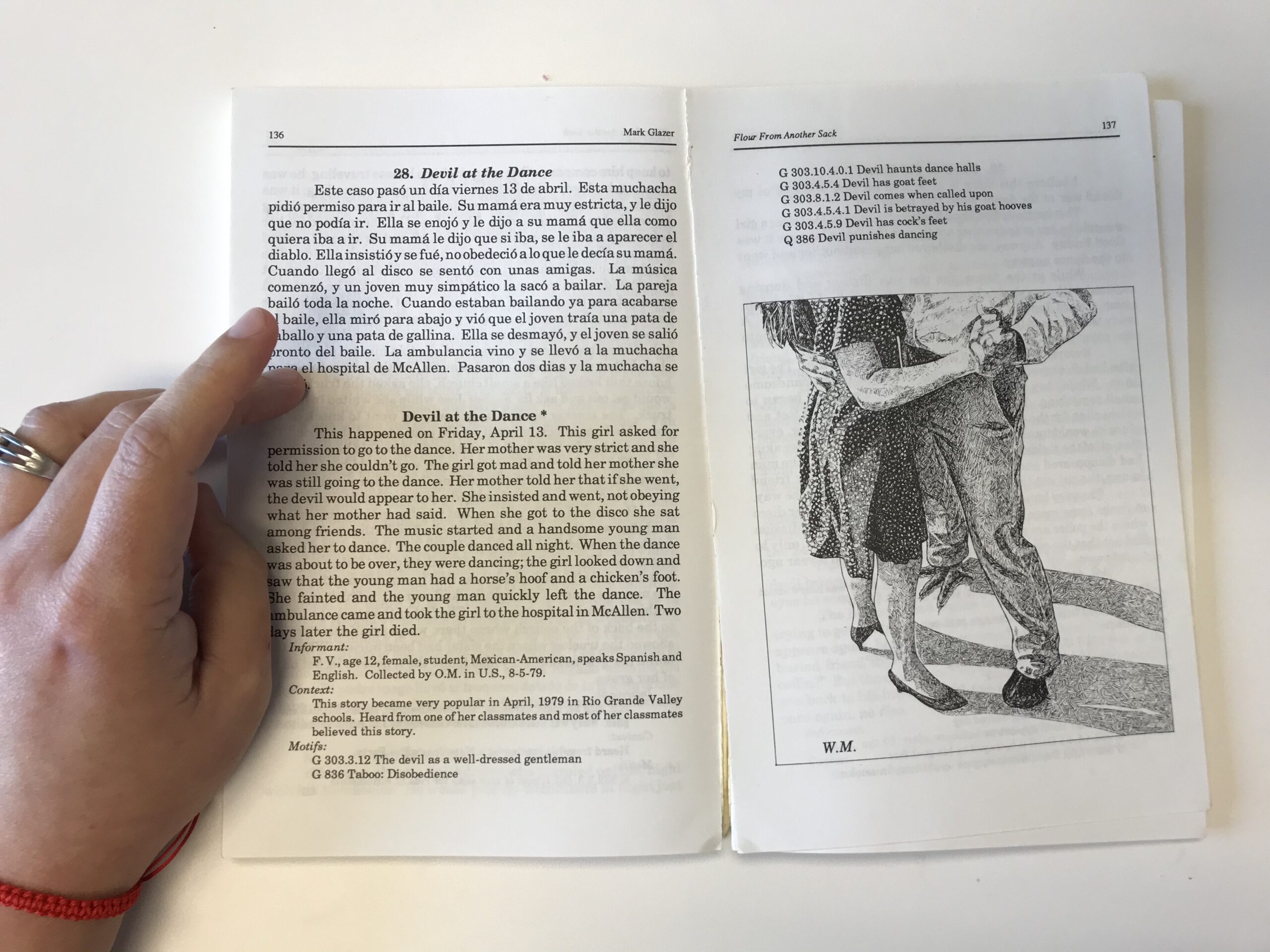

First person perspective of a student wearing a red string bracelet and ring reading Mark Glazer’s “Devil at the Dance” research.

First person perspective of a student wearing a red string bracelet and ring reading Mark Glazer’s “Devil at the Dance” research.

Reading Mark Glazer’s “Devil at the Dance” research.

Glazer attributes the folktale’s prevalence to socio-political changes in the Rio Grande Valley, particularly population growth, creating a temporal division between a “traditional” and “new” Valley. He suggests the story emerged during a liminal period of socio-economic change, reinforcing stricter adherence to traditional rules, especially for women, to quell anxieties about the unknown. The dancing with the devil meaning, in Glazer’s analysis, becomes a tool for social control during times of societal flux. Both participants in Glazer’s research emphasize female disobedience. However, the second account adds details like the stranger’s wealth and, crucially, the burning handprints left on the girl’s skin, highlighting the consequences of female sexual desire. Glazer’s systematic organization reveals the core cultural anxieties embedded in the story—female defiance and its punishment. While Glazer’s collection might not be a traditional settler archive, it functions as a site for producing “colonial difference and coloniality of knowledge” (García), where colonial logics and gendered oppressions intertwine. The inclusion of participants’ biological sex as data points reflects a Western research approach where gender, as Smith argues, is often reduced to roles and classifications rooted in Western cultural frameworks. The dancing with the devil meaning, as presented by Glazer, is thus framed within a colonial and patriarchal research paradigm.

Fragment 2: Limón’s Autoethnography and the Familiar Stranger

Jose Eduardo Limón’s Dancing with the Devil: Society and Cultural Poetics in Mexican-American South Texas takes a different approach, utilizing autoethnography. Limón’s research journey begins in a San Antonio Mexican restaurant where he encounters Sulema, a young woman who claims to have witnessed the devil at a nightclub. His initial interaction with Sulema is chaperoned, highlighting the social constraints and familial surveillance within the community. Sulema’s hesitation and unspoken questions – Familia? Quien eres tu? Que va a decir la gente? – reveal the deep-seated cultural norms and anxieties surrounding interactions with outsiders. Eventually, Sulema invites Limón to the nightclub, a space away from parental oversight, to discuss the story with her and her friends. Limón’s narrative positions him as a returning native, a “familiar stranger,” reintegrating into his South Texas roots, yet still holding the outsider status of an academic researcher. His description of going “again, on my way to a dance” highlights his dual role as both participant and observer, further shaping the dancing with the devil meaning through his subjective experience.

Limón’s autoethnographic method offers a stark contrast to Glazer’s objective approach. He is a Latino academic researching his own community, creating a different dynamic with his participants. Sulema introduces him to her friends as “the professor… anthropologist y quiere saber del diablo,” immediately framing him as an academic outsider interested in the devil story. Like Glazer, Limón, despite his insider status, still evokes a performance from his participants. The women he interviews are portrayed as playful and flirtatious, engaging with the story but also wary of Limón as a scholar. He becomes a “familiar stranger,” both part of and separate from the community, an outside observer looking in. The women in his research, in a sense, become secondary to his own rhetorical agency as a storyteller and researcher seeking to understand his community. Notably, Limón himself dances with the women, blurring the lines between researcher and participant. He describes dancing “with each of the women in turn… amidst moments of intense concentration, nervous laughter, and occasional glances toward the dance floor,” framing his experience as a way to “know the devil.” He presents his findings as a “general dialogue of voices, including my own,” emphasizing his subjective involvement in shaping the dancing with the devil meaning.

While distinct from Glazer, Limón also ultimately returns to Western methodological traditions, concluding his chapter with a theoretical analysis of the folktale within broader socio-economic and global contexts. He attributes the story’s intensity in South Texas to the region’s “shocking encounter with the cultural logic of late capitalism.” He argues that the changing agricultural economy led older generations to seek refuge in traditional moral structures, while younger generations, particularly women empowered by the Chicanx Movement, challenged these norms. Limón suggests that “the devil…appears to be a sexually charged site of admiration, delight, and playfulness for these women,” representing a rebellion against traditional morality. Limón’s heightened subjectivity allows for informal interactions and personal reflections absent in Glazer’s work. However, his narrative, still influenced by a colonial research paradigm and its inherent gendered implications, remains researcher-centered. Did Limón, by adopting a colonial academic approach with patriarchal undertones, inadvertently embody the “devil’s voice” in his retelling? Did he, metaphorically, become the devil dancing with these young Latinas? Limón’s research, while offering a shift in perspective, still reflects aspects of gendered oppression within the Chicanx community, shaping the dancing with the devil meaning through his particular lens.

Perhaps Western research methodologies, particularly for male scholars, are inherently limited in fully capturing the nuances of this folktale. A Chicana feminist perspective might offer deeper insights. Gloria Anzaldúa, in Borderlands/La Frontera, describes the Chicanx movement as a pivotal moment of self-discovery and collective identity formation. However, as Saldivar-Hull notes, the Chicanx movement often overlooked the roles of women. Chicana feminists have found agency in storytelling through art and poetry, offering alternative methodologies. Saldivar-Hull emphasizes the power of Chicana poetry to complicate and enrich self-consciousness, particularly as a feminist Chicana. Poetry, as a genre, invites unconventional engagement with words and images, allowing for a “critical imagination,” as Royster, Kirsch, & Bizzell describe it, broadening perspectives and revealing deeper meanings. This critical imagination offers a powerful tool for re-examining the dancing with the devil meaning from a feminist perspective.

Fragment 3: Ortiz’s Poetry and Revolutionary Love

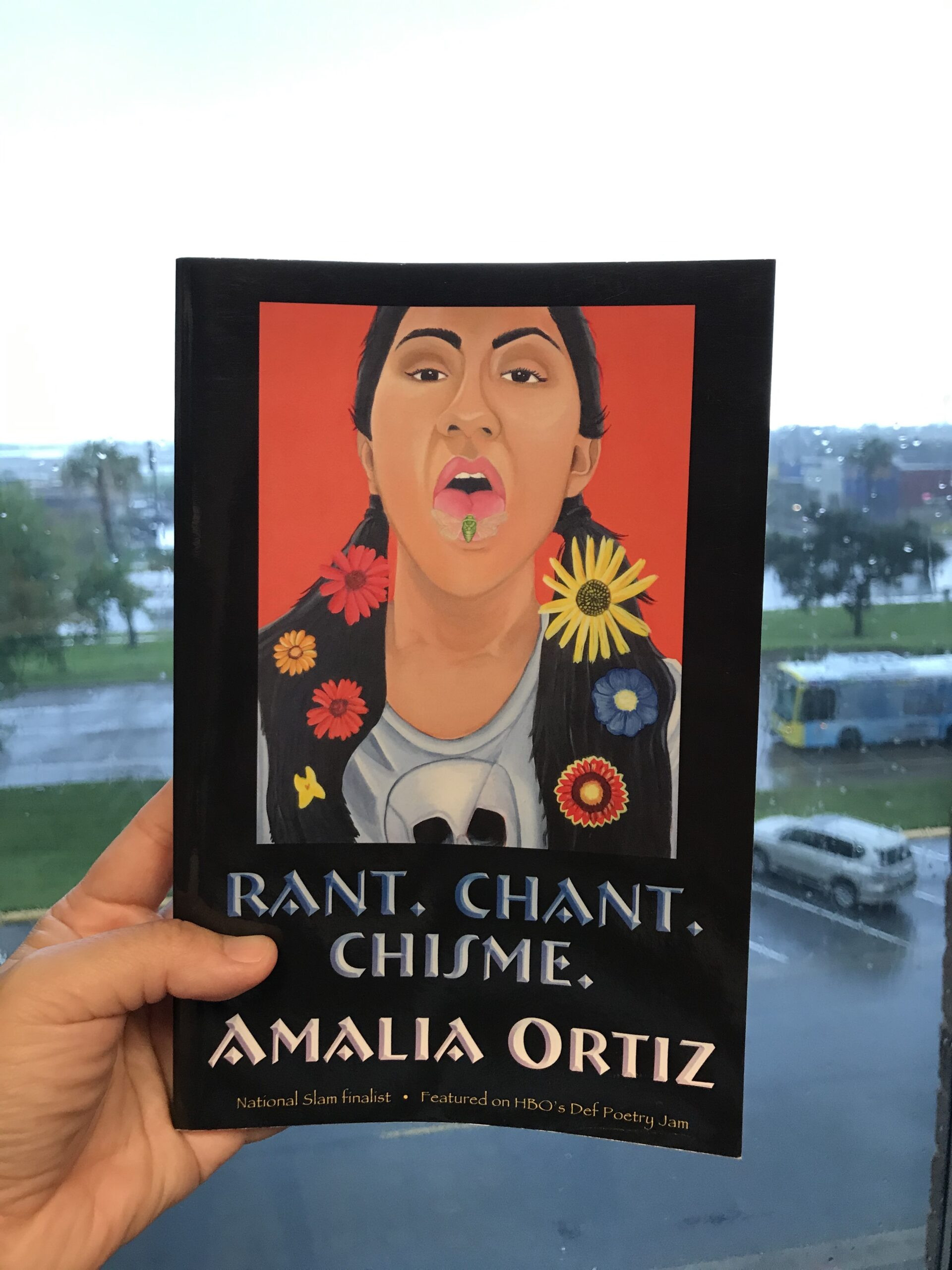

Amalia Ortiz, a Chicana spoken-word artist from South Texas, provides a transformative retelling of “Dancing with the Devil” in her poem “Devil at the Dance” from her collection Rant. Chant. Chisme.. Her work, rooted in border stories and experiences, offers a powerful counter-narrative.

A hand holds up a copy of Amalia Ortiz

A hand holds up a copy of Amalia Ortiz

A copy of Amalia Ortiz’s book, Rant. Chant. Chisme.

Ortiz’s poem begins in media res, with the young woman already dancing with the devil. The opening lines, “Her papá taught her to never look down. / A good dancer engages her partner’s gaze / or trustfully rests an ear on a strong shoulder,” immediately establish the protagonist’s adherence to parental teachings, framing her actions within a context of family values. While these paternal instructions reinforce some gender norms, they also counter accusations of disobedience prevalent in other retellings. Even as she defies her parents by going to the dance, she internalizes and applies their teachings in her interaction with her dance partner. Through the act of dancing with the devil, a connection forms. Karma Chávez, building on Aimee Carrillo Rowe’s work, discusses “coalitional subjectivity,” where individuals resist fixed identities and forge connections across differences. Ortiz’s word choices – “engages her partner’s gaze,” “trustfully rests an ear” – suggest an immediate trust and alliance forming between the woman and the stranger. She allies herself with the devil. This shift in subjectivity echoes Chela Sandoval’s concept of “differential consciousness,” which describes the ability to form coalitions across differences. Sandoval argues that “self-conscious agents of differential consciousness…[can] recognize one another as allies…[permitting] the practitioner to choose tactical positions…practices that permit the achievement of coalition across differences.” In Ortiz’s poem, by the time the protagonist notices the devil’s “hoof / the claw,” “it was too late,” a connection, a trust, a “coalitional subjectivity” has already been established – a “differential consciousness” opening the possibility for love, transforming the dancing with the devil meaning from a tale of punishment to one of potential connection.

Ortiz implicitly asks: what if the protagonist doesn’t die? What if her act of defiance isn’t punished, but instead becomes a moment of agency and connection? What if she dances with the devil and lives? Chávez further explains “differential belonging,” a strategy where groups choose to belong across lines of difference, challenging normative constructions of belonging. In Ortiz’s poem, the rhetorical agency shifts to the young woman, the subject and object of the original folktale. The poem’s powerful final lines – “[s]o, by the time she finally noticed the hoof / the claw tearing up the floor where shiny boots should be / It was too late. She was already in love” – reveal a radical reimagining of the story. Ortiz envisions the young woman surviving because her dance with the devil is not transgression and punishment, but an act of love born from embracing the feared “stranger.” Sandoval describes “Revolutionary Love” as a force that transcends ideology, “another kind of love, a synchronic process that punctures through traditional, older narratives of love, that ruptures everyday being.” Ortiz, through her poem, reconstructs the collective narrative, allowing for agency and alliance across differences. Her poem encourages crossing perceived boundaries in the name of this revolutionary love, fundamentally altering the dancing with the devil meaning.

By subverting the established narrative, Ortiz opens the story to broader transformations. Her poem shifts the agentive potential of both the woman and the devil, moving from individual subjectivity to a coalitional one. It demonstrates poetry’s methodological agency to break free from dominant narratives and enact stories outside traditional Western paradigms. The dancing with the devil meaning is not just about fear and punishment, but also about love, connection, and the potential for transformation.

One Concluding Fragment: Love and Possibility

“Dancing with the Devil” is a border story in multiple senses – a tale about borders taking place in a bordered region. The analyzed fragments reveal that the storyteller, the one controlling the methodology and circulation of the narrative, wields significant agency in shaping the overall story. Glazer and Limón, perhaps unintentionally, contributed to the story by reinforcing Western research methodologies and traditional gender paradigms. Ortiz, however, uses her poetic performance to grant agency to the protagonist, allowing her to speak and inject new meaning into the narrative. Her fragment subtly but powerfully shifts the dominant story, imbuing it with a coalitional spirit. The flexible, fragmentary nature of folktales allows for a move towards crossing borders into the unknown with love. The dancing with the devil meaning, therefore, is not fixed but constantly negotiated and reinterpreted through different voices and methodologies.

Reflecting on the journey of this research, the author notes how deeply intertwined the story has become with her own life since her initial conversation with her mother. Working on this analysis, she lived with the characters, contemplating how she too might contribute to the narrative, guiding it towards “coalitional, loving potentials.” Her poem, “Nine Months After the Burning of Club Boccaccio / McAllen, Texas (1979),” published in North Dakota Quarterly, further extends this reimagining. Written as a letter to the young woman’s parents, it introduces Joaquin, a child born from the love that began on the night of the dance. An excerpt highlights the poem’s focus on love and possibility:

Dad, I want you to love Joaquín and teach him how to fish

teach him to plant flowers and trees in the yard

I want him to help you mow the lawn

give your aching back a break

I want you to put one of your paint-covered cachuchas on Joaquín’s head

take pictures in the mirror

making silly faces together

Mom, I want you to teach Joaquin how to dance

like you taught me

yo se que todos son enojados conmigo, pero

Joaquín no tiene la culpa

He is a blessing, and

this disobedient daughter wants to come home

This poem foregrounds Joaquin’s potential for connection and the young woman’s desire to share love with her parents and son. Death and punishment are no longer central; instead, the poem leads with love and possibility, charting a new direction for this age-old story. The dancing with the devil meaning, ultimately, is not static, but a dynamic reflection of cultural anxieties, evolving interpretations, and the enduring power of storytelling to reshape our understanding of tradition, transgression, and love.

Works Cited

Agboka, Godwin Y. “‘Subjects’ in and of Research: Decolonizing Oppressive Rhetorical Practices in Technical Communication Research.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, vol. 51, no. 2, 2020, pp. 159–174., doi:10.1177/0047281620901484.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 2nd ed., Aunt Lute Books, 1999.

Boje, David. Narrative Methods for Organizational & Communication Research. Sage Publications, 2001.

Chávez, Karma R. “Border (In)Securities: Normative and Differential Belonging in LGBTQ and Immigrant Rights Discourse.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2010, pp. 136–155., doi:10.1080/14791421003763291.

Gaffney, Sean. “An Eye-witness Speaks about the Night the Devil Danced at Boccaccio’s.” The Monitor. 30 Oct. 2009.

Galván, Marlene. “Nine Months After the Burning of Club Boccaccio / McAllen, Texas (1979).” North Dakota Quarterly, vol. 86, no. 3/4, 2019, pp. 62.

García, Romeo. “A Settler Archive: A Site for a Decolonial Praxis Project.” constellations: a cultural rhetorics publishing space, no. 2, 14 Dec. 2019, constell8cr.com/issue-2/a-settler-archive-a-site-for-a-decolonial-praxis-project/.

Glazer, Mark. Flour from Another Sack & Other Proverbs, Folk Beliefs, Tales, Riddles, & Recipes. University of Texas-Pan American Press, 1994.

King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories: a Native Narrative. House of Anansi Press, 2011.

Limón José Eduardo. Dancing with the Devil: Society and Cultural Poetics in Mexican-American South Texas. University of Wisconsin, 1994.

Martinez, Aja. “The Responsibility of Privilege: A Critical Race Counterstory Conversation.”

Peitho: Journal of the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, vol. 21, no. 1, 2018, pp. 212-233.

Ortiz, Amalia. Rant. Chant. Chisme. Wings Press, 2015.

Mukavetz, Andrea M. Riley. “Towards a cultural rhetorics methodology: Making research matter with multi-generational women from the Little Traverse Bay Band.” Rhetoric, Professional Communication, and Globalization, vol. 5 no.1, 2014, pp. 108-125.

Palleiro, María Inés. “Cuento folklórico y narrativa oral: versiones, variantes y estudios de génesis.” Cuadernos LIRICO. vol. 9, 2013, https://doi.org/10.4000/lirico.1120.

Phelan, Shane. Sexual Strangers: Gays, Lesbians, and Dilemmas of Citizenship. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Royster, Jacqueline Jones., and Gesa E. Kirsch. Feminist Rhetorical Practices: New Horizons for Rhetoric, Composition, and Literacy Studies. Southern Illinois Univ. Press, 2012.

Saldívar-Hull Sonia. Feminism on the Border: Chicana Gender Politics and Literature. University of California Press, 2006.

Sandoval, Chela, and Angela Y. Davis. Methodology of the Oppressed. University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Sandoval, Chela. Oppositional Consciousness in the Postmodern World: U.S. Third World Feminism, Semiotics, and the Methodology of the Oppressed. 1993.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed., Zed Books, 2012.

“The Devil Danced at Boccaccio 2000.” Jorge’s House of Horrors, 2021, jorgeshouseofhorrors.com/the-devil-danced-at-boccaccio-2000/. Accessed 23 Apr. 2021.

Please note: This article is for informational purposes only and does not offer definitive interpretations of folklore. The dancing with the devil meaning is culturally nuanced and open to individual understanding.