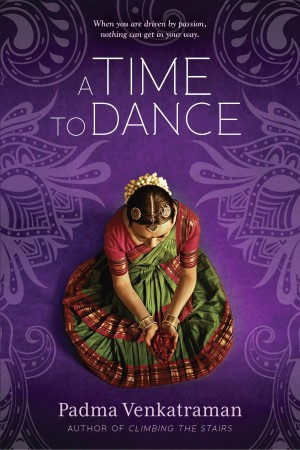

Padma Venkatraman’s A Time to Dance is more than just a young adult novel; it’s a powerful narrative brimming with resilience, passion, and the transformative power of dance. For those captivated by dance films and stories of overcoming adversity, A Time to Dance offers a rich source of inspiration, prompting the question: Could this compelling book be the next must-see dance movie?

The novel introduces us to Veda, a teenage dancer whose life takes an unexpected turn after a car accident results in the amputation of her right leg. Her dreams seem shattered when her dance teacher suggests she find a “new dream.” This pivotal moment, depicted with raw emotion in the book, sets the stage for Veda’s journey of rediscovery. Instead of succumbing to despair, Veda embarks on a path of physical and emotional rehabilitation, challenging societal expectations and redefining her relationship with dance.

This premise alone holds immense cinematic appeal. Dance movies often resonate with audiences by showcasing breathtaking choreography and the dedication required to master this art form. However, A Time to Dance offers a depth rarely explored in the genre. It delves into the authentic experience of disability, moving beyond simplistic tropes of tragedy or inspiration. The book masterfully avoids portraying Veda as either a victim or a superhuman figure. Instead, it presents her as a complex, relatable teenager navigating the challenges of amputation while grappling with universal adolescent experiences like friendships, family dynamics, and first love.

The strength of A Time to Dance lies in its realistic portrayal of life as an amputee. Venkatraman’s meticulous research and collaboration with amputees and healthcare professionals are evident throughout the narrative. Details, like Veda’s prosthetist using plaster of Paris to create a mold for her prosthetic limb, ground the story in tangible reality. This commitment to accuracy extends to the emotional landscape of amputation. The book unflinchingly explores Veda’s physical pain, including phantom pain and scar discomfort, and her emotional journey, marked by moments of frustration, vulnerability, and gradual acceptance.

My phantom comes alive.

Beneath my right knee,

Nails scratch at invisible skin. (p. 264)

This quote, capturing the unsettling sensation of phantom pain, exemplifies the book’s ability to immerse the reader in Veda’s lived experience. For viewers of a potential A Time to Dance movie, this level of authenticity would be both educational and deeply moving. It offers an opportunity to broaden understanding and empathy towards individuals with disabilities, moving beyond superficial portrayals often seen in mainstream media.

Another compelling aspect of A Time to Dance that would translate powerfully to film is Veda’s resilience and determination to dance again. While the book doesn’t shy away from the difficulties Veda faces, it ultimately celebrates her strength and adaptability. Her journey is not about miraculously overcoming her disability to return to her former self, but about evolving as a dancer and redefining what dance means to her. This nuanced perspective on resilience is far more compelling than simplistic narratives of “triumph over tragedy.”

Dance movies often thrive on visual storytelling, and A Time to Dance provides ample opportunities for breathtaking cinematic moments. Imagine the emotional impact of scenes depicting Veda’s initial struggles to regain her balance, contrasted with her eventual return to the dance floor, perhaps even incorporating adaptive dance styles. The visual language of dance, combined with the emotional depth of Veda’s story, could create a truly unforgettable movie experience.

While A Time to Dance primarily focuses on Veda’s individual journey, the book also touches upon the importance of community and role models. One poignant scene depicts Veda meeting other amputees at her prosthetist’s office, where she experiences a sense of belonging and normalcy.

I meet a girl who says she kicks the soccer ball

better with Jim’s leg than her own.

A middle-aged woman makes me laugh

as she expounds the virtues of being one-legged:

“Cuts pedicure bills in half.”

At this party …

two-legged people are in the minority.

We amputees are the norm. (p. 181)

This brief glimpse into a community of amputees highlights a missed opportunity in the book, as the reviewer points out. However, a movie adaptation could expand upon this aspect, showcasing the power of peer support and disability communities. Including scenes where Veda connects with other amputee dancers or mentors could further enrich the narrative and provide a more comprehensive portrayal of disability experience.

Furthermore, the book’s inclusion of famous amputee dancers, whose pictures inspire Veda in her prosthetist’s office, offers another avenue for cinematic exploration. A Time to Dance movie could weave in real-life stories of amputee dancers, celebrating their achievements and further emphasizing the message of inclusivity and breaking barriers in the dance world.

In conclusion, A Time to Dance possesses all the essential elements to become a remarkable and impactful dance movie. Its compelling protagonist, authentic portrayal of disability, and uplifting message of resilience offer a refreshing departure from typical dance movie tropes. By focusing on Veda’s emotional journey and the transformative power of dance, a film adaptation of A Time to Dance has the potential to not only entertain but also to educate and inspire audiences worldwide, prompting important conversations about disability representation and the boundless nature of human potential.